Outer Banks Shipwrecks: The Tale of the Storm-Tossed Ario Pardee, And How a Day-long Trip Turned into a 152-Hour Odyssey

A great many folks, past and present, celebrate year’s end around the holidays with the feasts of Thanksgiving and the joy of giving at Christmas. Then, it is topped off with the late-night parties of New Year’s Eve. The crew of the schooner Ario Pardee certainly must have anticipated this joyous time when they set sail in mid-December of 1884. It would instead be their worst nightmare.

It would be extremely difficult to top the amazingly painful story of “Dunbar Davis’s Longest Day.” In that tale, beginning on Tuesday, August 29, 1893, fifty-year-old Keeper Dunbar Davis of the Oak Island Station, N.C., spent 55 consecutive hours without sleep, food or water while responding to five different wrecks, one after the other, and mostly on his own.

However, almost unbelievably, the 198-ton, three-masted schooner Ario Pardee would endure an incredible 152 hours in five consecutive storms before finally becoming a total loss at the Wash Woods Life-Saving Service Station on the northern Outer Banks near the Virginia border. This would be nine years before Dunbar Davis’s soggy saga at Oak Island, at the extreme opposite end of coastal N.C.

The five men aboard the Ario Pardee – Ship Master Henry A. Smith and crewmen John W. Comer, Ole Jensen, John Force and Thomas B. Allen – not only outdid Dunbar Davis’s marathon, but exceeded it by a factor of ten!

The trip’s itinerary was very simple: Go from Perth Amboy, New Jersey, to nearby Chester, Pennsylvania. This was approximately ninety miles, and almost any sailing ship of the day could easily make that trip in a day or two at most.

The Odyssey Begins

Usually one thinks of the Greek poet Homer when hearing that word. It is most correctly used, however, since Merriam-Webster defines an odyssey as “a wandering or long voyage usually marked by many changes in fortune.” This voyage of the schooner Ario Pardee is a perfect example of that.

The Captain writes, “I sailed December 8, 1884, from Perth Amboy, with a crew of five men, all told, on the schooner A. Pardee, of Perth Amboy, bound from the port of Rondout, New York, to Chester, Pennsylvania, with a cargo of cement.”

Although this is from the captain’s own report, the December 8 date is clearly incorrect. All records indicate the odyssey lasted ten days, not the 32 days total if she left on the eighth. Furthermore, Outer Banks author and historian David Stick, renowned for his thorough and meticulous research, puts the date as December 18. The original Captain Smith 1884 document’s date is easily explained as a simple typo or one keystroke error in a transcript.

“Sailed at 7 a.m. Wind northwest. Passed Sandy Hook [N.J.] 11 a.m. When abreast of Long Branch, the wind shifted to north, and commenced to snow. At 6 p.m., wind blowing a gale from the north, took in sail, and run the vessel before the wind under a reefed mainsail and jib.” Then he calmly adds, “Gale lasted fifty-six hours…” This strong north wind is blowing and pushing the Ario Pardee to the south, precisely in the opposite direction the captain wanted to go.

That entry is from 6:00 p.m. on Monday. The gale lasted all through that night, then all the next day and night on Tuesday, and all day and night on Wednesday, then all day on Thursday before finally ending at 2:00 a.m. on early Friday morning. This, however, was just the first storm.

It boggles the mind to imagine what these four men were doing all that time. Captain Smith does not say, nor does the “Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1885.” which only describes the lifesavers’ rescue.

Using the modern definition of “gale,” this means there were sustained winds ranging from 39 to 54 mph. At its maximum, such winds can produce ocean wave heights from 18 to 32 feet. Only winds produced by what is technically named a “storm” or a “hurricane” will exceed that.

For those fifty-six straight hours, then, the schooner was constantly being tossed about, perpetually unstable and out of balance, “in which we had continuous high seas, washing everything movable from deck; stove water casks and split sails,” as Captain Smith describes.

Walking or even standing would be like imitating a drunken sailor. Sleeping would be well-nigh impossible. Eating was almost out of the question, for no cook stove could be lit for danger of burning down the ship. What was left? Warm beer and hard, stale ship’s biscuits and perhaps some cold canned goods.

A Second and Third Gale

In spite of all that, Smith says not a word. Instead, his very next sentence is, “Afterwards took a gale from south, lasting about twenty-four hours, and run before that.” He means to sail away from the storm, keeping the stern in front of the storm. “This tactic requires a lot of sea room, and the boat must be steered actively.” He does not say what happens or what they did during that time, just that it is another full day of stormage. We do not know exactly where the Ario Pardee is at this time, and Smith probably doesn’t either.

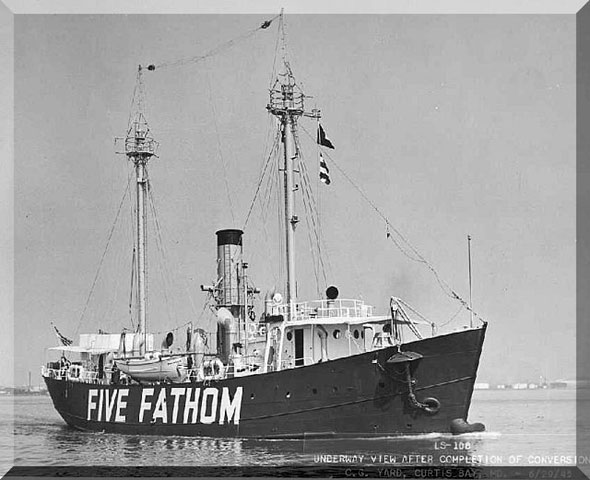

Presumably shortly after that, Smith says simply, “Then took a gale northwest and run that out.” He does not say how long this third gale lasted or how they handled it, other than “running it out.” But the good news, finally it might seem, was that the winds had calmed down enough for Captain Smith to take control of the schooner, so he “made what sail we could and run for land.” The battered but manageable vessel made it to the lightship off of Five-Fathom Bank. Located in the Atlantic Ocean to help guide vessels to the Delaware Bay, the original lightship was recommended for establishment in 1826. Over the years, several ships endured the rough weather and heavy seas at the site, and it was replaced several times.

Almost Unbelievably, Yet More Storms

About five miles out from lightship LV-40, (which served from 1877 until 1904), Smith is struck by yet another gale, this one westerly, which would push him towards the Delaware shore. The Pardee rode out this storm for another twelve hours. At least now Captain Smith knows where he is, and it is dreadfully off-course.

After passing another half day going nowhere, the winds abate, allowing Smith to make sail and head for land. Nothing would be that easy on this day, however. Coming tantalizingly close to a safe landfall, Pardee makes it to the Indian River Inlet, heading for the Delaware Breakwater, when it is struck by strong north winds. Now about five miles from Cape Henlopen to the northwest, winds “blew away jib. Hove the vessel to again, wind blowing a gale and snowing.”

Beginning of the End

Could it get any worse? You might guess by now that it certainly would.

By the next day, the schooner was seriously damaged, broken, and leaking badly. It was time to run up the proverbial white flag. Due to extremely overdue good luck, the steamer Chattahoochie was nearby. Smith contacted her and asked if she could take him and his crew off their storm-battered vessel.

Captain J. W. Catherine of the Chattahoochie of the Savannah Line reported spotting the disabled vessel at 2:30 p.m. and stated that she was flying her ensign upside down, an international maritime signal of distress. A New York Times article of December 28, 1884 reports that the Pardee was rolling in such a dangerous manner, it was impossible to get alongside the vessel. The article continues ominously, “For several moments the occupants of the [life]boat seemed in much greater danger than the people on the schooner.” Sailor Thomas B. Allen of the Pardee was finally rescued, but it was getting dark, and rain and sleet started to fall, so the steamer withdrew. At that time, sailor Allen reported that the Pardee already had four feet of water in her hold.

Sadly, Smith reports, “The steamer made two attempts to take us off. They got one man by life buoy and line. The sea running very high and night coming on, she left us.”

Now that Captain Smith has one less crew member, a broken and sinking ship, and he’s still in a storm.

With no other options, he heaves to again, and endures the final battering for another sixty hours!

At midnight, ten days later, Smith happily reports that, “we sighted a bright red light ahead and saw breakers. Let go both anchors. In a short time saw lights on shore and heard guns fired at intervals during the night. Heard two shots pass over the vessel but could not find any line. At daylight we discovered that we were near a lifesaving station and saw signals by flags. We had no code to answer signals. Set our ensign in distress.” The bright red light was actually the Currituck Beach light, and the guns fired during the night were the Lyle gun from the United States Life-Saving Service Station, Wash Woods.

From the Annual Report, “Just before midnight of the 28th the south patrol of the Wash Woods Station (6th District), North Carolina saw a schooner close in, about a quarter of a mile south of the station. The sea was running high, and the weather was thick and foggy. He hurried to the station and reported his discovery to the keeper, who at once turned out the crew and had the beach apparatus hauled down the shore to a point abreast of the vessel and placed in position.”

The Annual Report continued, “By this time the crews of the False Cape [V.A.] and the Currituck Beach Stations [N.C.] arrived on the ground to render assistance.” The surf boat was soon successfully launched, and the lifesavers were able to board the wounded schooner. Keeper Corbel provided each of the vessel’s crew members with a cork life preserver and placed them and their baggage in the boat, and at 9:00 a.m. that morning, all of them had safely landed.

Then Captain Smith concludes, “Vessel still afloat, but sea running very high. At 10 a.m. vessel parted chains and came ashore, and soon began breaking up. Vessel was about a quarter of a mile from shore, in two and a half fathoms of water, when we were rescued by Captain Corbel [keeper of the Wash Woods Station, usually referred to by all as “Captain”] and his brave crew, and only for their aid we would most likely have all been lost. We, the master and crew of the schooner Ario Pardee, desire to return our most sincere thanks to Captain Corbel and his men for their timely rescue of us from our perilous position and their kind treatment of us since.”

The crew was sheltered at the Wash Woods Life-Saving Station for another twelve days. As was Standard Operating Procedure at all U.S. Life-Saving Stations, the survivors were given a place to stay, dry clothes, meals, and any needed first aid. Captain Smith had lost his shoes and was provided a pair from the station’s stockpile, provided by the Women’s National Relieve Association.

The vessel and cargo were a total loss. Ship Master Henry A. Smith and crewmen John W. Comer, Ole Jensen, and John Force were alive, and had survived an impossible string of 152 hours of storms.

Finally Home, but not for the Holidays

Far too many days, twenty-two of them, after leaving port in Perth Amboy, N.J., their arduous storm-tossed schooner trip was over. Ironically, along the way they had passed 65 United States Life-Saving Service Stations: 41 in New Jersey, six in Delaware, thirteen in Maryland and five more in Virginia. They also would have passed too many lighthouses to list here!

Today, we know that a holiday is a joyous, fun celebration and/or a vacation. This grueling odyssey was clearly the opposite of that. However, when it is realized that the word “holiday” comes from the old English, “holy day,” this takes on an entirely different meaning. Yes, the crew had missed the holidays of Christmas Day and New Years’ Day. But they arrived home through the grace of God just as a New Year was beginning. Surely a holy day for them.

About the Author:

James D. Charlet is an authority on the US Life-Saving Service on North Carolina’s iconic Outer Banks, and contributes to local and national media with articles on Outer Banks and nautical history. James taught North Carolina history for twenty-four years and authored a state-adopted textbook on the subject. He has worked with the Wright Brothers National Memorial, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, was Lead Interpreter at Roanoke Island Festival Park (celebrating the Roanoke Voyages), and – most importantly – has been involved with the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station Historic Site & Museum for twenty-one years and was the site manager of the Historic Site for ten years, retiring from there in 2015.

James’ new book on dramatic OBX shipwrecks and rescues is due in March. He is currently working on a sequel for the same national publisher. He is a regular contributor to Island Free Press, Coastal Review Online, My Outer Banks Home and has a feature article in the 2019 Outer Banks Magazine. In his spare time, James has leads tours, educational programs, and speaking engagements and live presentations as “Keeper James.”