The Steamer Ariosto, and the ‘Entirely Needless’ Christmas Eve Tragedy on Ocracoke Island

This is a story about a huge disaster that could have easily been averted. It is a story with negatives and positives. It is a story of a captain’s confusions, the terror of panic, and the avoidable loss of thirty human lives.

Unhappily, it was on Christmas Eve. Ironically, it took place in a year of enormous unavoidable tragedies. But it is also the story of the amazing tenacity of the American surfmen and lifesavers, and of their teamwork with neighboring stations and volunteering residents.

Prologue

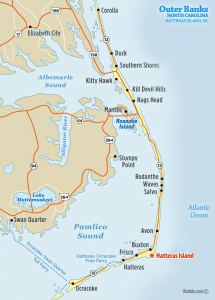

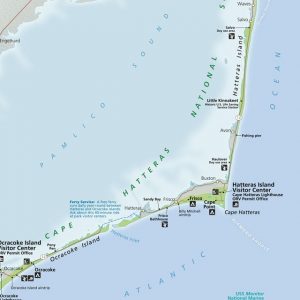

The year 1899 on the Outer Banks will always be known as the year of the worst hurricane ever, with the most shipwrecks, destruction, and loss of lives on Hatteras Island at that time. It was in August, and in a time before storms were named, but this one would forever be called San Ciriaco. The “Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Services” that year starts sternly: “The most calamitous, because entirely needless, loss of life during the entire year, or indeed for many recent years in the history of the Service, occurred on December 24, 1899, at the wreck of the British steamship Ariosto on the coast of North Carolina about 2 miles to the southward of the Ocracoke Life-Saving Station. Of 30 persons on board the vessel, 21 perished, while there was in the conditions not the slightest necessity that a single one should have been lost.”

The Ship

The Ariosto was a schooner-rigged steel steam-powered vessel of 2,265 tons and was owned by R. McAndrews & Co. of London. Only seven years old at the time of this voyage, she was laden with a very valuable cargo of wheat, cotton, lumber, and cotton-seed meal valued then at $1.5 million dollars, (approximately $45 million today). This large schooner was carrying 30 men, including officers, and was commanded by Captain R.R. Baines. She was bound from Galveston, Texas, to Hamburg, Germany, via Norfolk, V.A., the object of the call at Norfolk being to refill the coal bunkers. Due to its mid-Atlantic location and the size and ease of accessing its ports, the Hampton Roads area remains a major coal suppler of steamships today.

The Setting

Late on the evening of December 23, the weather began to deteriorate. The Annual Report tells us: “At midnight, the weather was thick all around, and heavy showers of rain passed over from time to time, while the sea was constantly making.” Winds were gusting 40-50 miles per hour. Just before 4:00 a.m., while asleep in his cabin, Captain Baines was awakened by a request from the First Mate to join him on deck. To his great surprise, Captain Baines saw that his ship was completely surrounded by “white water,” meaning it was in shallow breakers, usually occurring only close to shore. This surprise slowly turned into terror as Baines was trying to figure out where he was and what to do about this dangerous situation. He knew that he was somewhere off the North Carolina coast. Since he could see no land, he judged that they were most likely in the midst of the infamous Diamond Shoals, extending twenty miles out to sea from Cape Hatteras. If that were the case, immediate action was required.

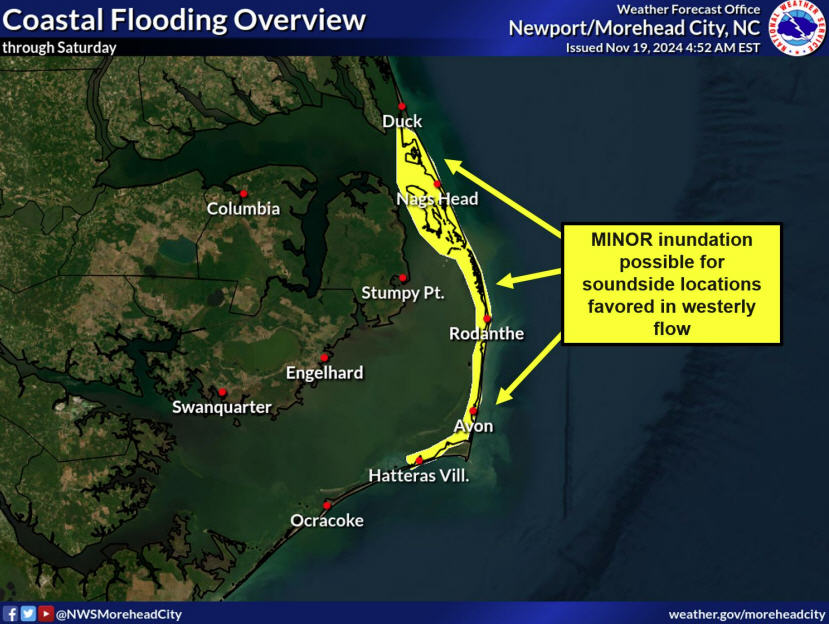

As it turns out, the Ariosto was located fifteen miles to the southwest of Diamond Shoals, near Ocracoke Island and the Ocracoke U.S. Life-Saving Service Station commanded by keeper Captain James Howard.

The wind and surf pushed the heavily laden cargo schooner farther into the breakers where she grounded and was “bumping and thumping in such a manner that it seemed probable her masts would come down,” comments Captain Baines in the Annual Report. All hands scurried to the weather deck and began to fire off distress rockets; so far, the correct procedures. Then, a red flash of light was seen to the north, hopefully a sign of assistance. Indeed, it was. Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for the United States Life-Saving Service was the beach patrol to fire a red Costin flare after spotting a shipwreck. This one came from the Ocracoke Station beach patrol by surfman Guthrie.

The rough seas had already destroyed the starboard lifeboats and was rolling the Ariosto so violently to the port side that Captain Baines feared the lifeboats on that side would also soon be lost. He immediately ordered them launched and for the crew to abandon ship. “Here was where the fatal mistake occurred,” the Annual Report laconically states.

From the earliest days of the Service, the lifesavers knew well that the number one cause of injury and death from shipwreck victims was leaving their ship in a panic. The lifesavers routinely conveyed this message in many ways. To expedite having the shipwreck crew successfully set up the Breeches Buoy, the United States Life-Saving Service published a booklet of instructions with text and diagrams printed, which was to be aboard all sailing vessels. It was entitled “Instructions To [sic] Mariners In Case Of Shipwreck: With Information Concerning The Life-saving [sic] Stations Upon the Coasts of the United States.” On page 7, it says, with their italics for emphasis, “Masters [ship captains] are particularly cautioned, if they should be driven ashore anywhere in the neighborhood of the stations, especially on any of the sandy coasts where there is not much danger of vessels breaking up immediately, to remain on board until assistance arrives, and under no circumstances should they attempt to land through the surf in their own boats until the last hope of assistance from the shore has vanished.”

This was the fatal mistake. One that had been made so many times over so many years with the entirely needless loss of so many lives.

Confusing Circumstances

In his defense, if Captain Baine’s assumption of his location had been correct, he had little other choice but to abandon ship, for he would have been as much as twenty miles from shore in a location infamous for wrecking ships.

No U.S. Life-Saving station would be anywhere near nor able to assist a vessel that far out, or so he thought. But they had seen a flare; surely that meant rescue was imminent. It is hard to judge someone for panicking in such a terrifying situation and things were happening so fast. Panic indeed was the determining factor in launching the lifeboats: “It would appear that these entire operations were conducted with such haste that they were completed in less than 30 minutes from the moment the vessel stranded,” the investigations by the Service found in the Annual Report.

Still, the captain’s plan was not entirely flawed. His objective was to get the crew off the schooner into the two remaining lifeboats, but to have them lay in the lee side of the large schooner, thus protected from the strong winds. Hopefully, they would therefore be safe until morning when their position could more correctly be determined. That was the plan. The reality was this: all but four – Captain Baines, Third Officer Reed, Chief Engineer Warren, and Carpenter Peltonen – got away into the lifeboats. For those four, it was a happy accident. Soon afterwards, both lifeboats capsized. The drama is described: “Twenty-six persons were now battling for their lives in one of the worst seas with which desperate men have ever contended. And yet one of them, Seaman Elsing, a man of infinite skill in the water and of brave heart and wonderful physical power, actually swam ashore, absolutely unaided even with so much as the slightest piece of wreckage to help bear him up.” All but four of the passengers on the lifeboats drowned. Two were retrieved by the schooner, while two more remarkably were pulled from the rough surf by the lifesavers on the beach. It was reported by a 2017 article fittingly written by Philip Howard of Ocracoke that “Captain Baines, on the wrecked vessel, as he saw his men perish—this mariner who had sailed the world over for twenty-five years—wept like a child.”

Monday Morning Quarterbacking – Hindsight

Captain Baines originally judged that his ship would go to pieces quickly, and thus decided to abandon ship. In fact, the ship remained completely intact for several days. Once the Ocracoke station lifesaving crew was abreast of the wreck, keeper Howard gave the signal “remain by your ship” using the International Signal Code Flags. Much travail, obstacles to overcome and coordination of plans and resources would then occur for the lifesavers to get into position. That is what they do. Routinely.

The Lifesavers Response

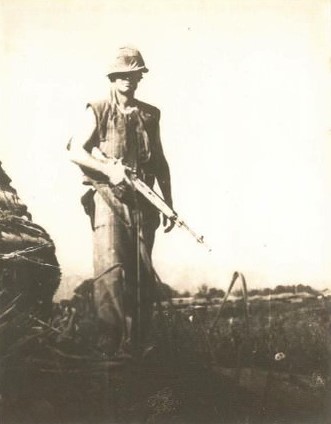

Ocracoke station’s beach patrols, both the north patrol and the south one, had spotted the wreck around 4:00 in the morning of Christmas Eve. Upon returning to his station, surfman Davie Williams, the north patrolman, found his crew already in motion. Starting out in the dark was not a problem, until the surfmen encountered a deep inlet scoured out by the San Ciriaco hurricane in August. Here, they were assisted by five local citizens to get their heavy beach apparatus cart across the waters. They reached the wreck by 5:30 a.m. and soon discovered half-conscious Seaman Elsing, who had miraculously swam ashore by himself. He debriefed the surfman on the situation as best he could, and they commenced immediately to set up the Breeches Buoy apparatus.

Anyone witnessing a modern reenactment of the beach apparatus drill is always amazed at the speed and complexity of the performance. It is a difficult procedure, requiring skill, knowledge and experience. Yet it is done in the daytime, in great weather conditions. What the modern visitor may not realize is that the actual rescues were done under far more trying conditions. The modern reenactor surfmen simply bury the sand anchor quickly and plop down the Lyle gun in preferred locations. Not so for keeper Howard’s crew this dark and stormy night!

The Rescue Begins

Due to the high surf, they had to frequently relocate both the sand anchor and the Lyle gun. In addition, the schooner was at the very extreme range of the Lyle gun’s shot.

Then a Christmas miracle happened. The first shot expectedly fell short, so it was hauled back in. “And with it came a half-drowned man, who was later found to be Boatswain Andersen. He was unconscious, but was resuscitated by the surfmen, and subsequently told them that the [shot]line fell across him as he was struggling in the surf; that he had sufficient consciousness to hitch it around his arm, and was thus drawn ashore—an almost miraculous escape from death.”

Inspired by that miracle, the surfmen lunged into the heavy surf, at times up to their necks, searching for more sailors. Several were found, but only Fireman Henroth was alive. Numerous shots continued to be fired, but all fell short due to the distance and conditions. Neither the ship nor the lifesavers’ equipment remained stationary; the schooner’s continued movement and rolling in the surf caused constant adjustments of the beach apparatus.

Here, the Annual Report compliments the Ocracoke surfmen: “For these reasons the operations were necessarily so extremely difficult that their completion without mishap affords the best of evidence that they were judiciously and skillfully conducted.” It was not until 11:00 a.m. that a No.4 shotline, the smallest, finally was successfully placed over Ariosto. But the difficulties remained. A No.7 and No. 9 shotline were added so the heavy hawser could finally be sent out and all remaining on board could be taken safely ashore by the Breeches Buoy. It was at this time that Keeper Burrus and his crew of the Durants Life-Saving Station arrived to assist. They had left earlier, but due to the weather conditions, they had to take a longer route to get to the scene.

Following a long-standing nautical tradition, Ariosto’s Captain Baines was the last off the ship. When his feet hit the beach at 2:30 that afternoon, “a loud cheer was sent up by all the people who had by this time assembled.”

The Annual Report praised the Durants Station for their cooperation, and also complimentrf the local citizenry. Interestingly, the Report specifically mentioned the resident family names of Stowe, O’Neal and Austin – names still prominent in Ocracoke today. Still, it was made clear that “under the most unfortunate circumstances following the launching of the boats, and if all had remained patiently on board not one would have been lost.” Just as so many had been told so many times before. An “entirely needless” loss of life, indeed.