Somewhere around 4:30 p.m. on Thursday, Sept. 13, under a large party tent in the backyard of the historic Seaside Inn, Ernie Foster stepped onto the stage and grabbed the microphone.

Just minutes earlier, an unexpected late-summer storm had unleashed torrential rains, forcing the 80 or so guests who had gathered for the first event of this year’s Day at the Docks festival into the tent.

“Well,” he said with a smile, “I guess this is probably an appropriate way to begin a fisheries meeting in Hatteras.”

Appreciative chuckles rippled through the audience, and with that, the annual Day at the Docks had officially kicked-off.

If the storm seemed an appropriate way to begin Thursday’s discussion, then the discussion itself—titled “Talk of the Villages: Fishermen, Fish, Food, and Livelihood”—seemed like a perfect way to begin this year’s extended event.

When Ernie and his wife Lynne, the founders and organizers of Day at the Docks, decided to expand the event this year—from a one-day celebration along the Hatteras waterfront to a four-day, village-wide affair—it was with the idea that Day at the Docks could function not only as a means to celebrate watermen and honor the island’s fishing tradition, but also as a tool to help actively preserve that heritage.

Lynne said that she hoped that the new additions to the Day at the Docks line-up—and “Talk of the Villages” in particular—would help uplift the fishing community and inspire watermen to become leaders in the fishing industry.

To that end, the Fosters—in cooperation with event sponsors North Carolina Sea Grant, North Carolina Watermen United, Northwest Atlantic Marine Alliance, and Saltwater Connection—assembled a panel of fishermen (and women) and fishing industry advocates from across the nation to share their personal experiences in the industry and discuss the future of Hatteras Island fisheries.

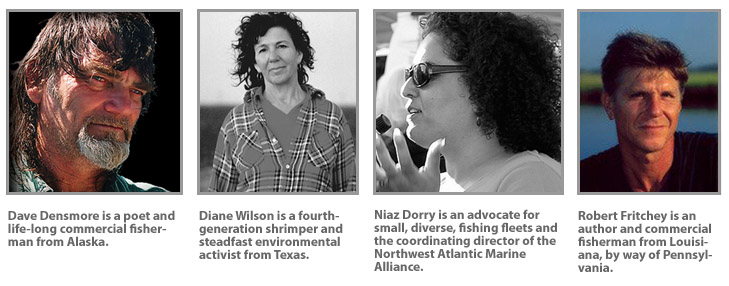

Featured guests included: Dave Densmore, a poet and life-long commercial fisherman from Alaska; Diane Wilson, a fourth-generation shrimper and steadfast environmental activist from Texas; Robert Fritchey, an author and commercial fisherman from Louisiana (by way of Pennsylvania), and Niaz Dorry, an advocate for small, diverse, fishing fleets and the coordinating director of the Northwest Atlantic Marine Alliance.

The discussion, which was moderated by Susan West and Barbara Garrity-Blake, who co-wrote the book, “Fish House Opera,” essentially focused on the question of whether it is possible to have healthy fish stocks as well as healthy fishing communities.

After thanking the Seaside Inn for hosting the event, crediting the sponsors and organizers who had worked to make the whole thing possible, and recognizing the local political officials who attended—including County Commissioners Warren Judge, Mike Johnson, and Allen Burrus, as well as state Sen. Stan White—Foster turned the discussion over to West.

West briefly introduced the panelists, and opened the discussion by asking Densmore what motivated him to continue fishing, despite having felt incredible painful loss and having faced life-threatening accidents on the water.

Densmore, who now lives in Oregon and, in addition to fishing, writes poetry about commercial fishermen and their work, spoke about his experiences.

In 1971, he spent four frigid nights in a life raft, adrift on the Bering Sea without a survival suit, after a king crab boat he was running caught fire and burned. He and his men were rescued by a Japanese trawler and miraculously survived, but the incident landed him in the hospital for a month, and it took him two years to recover from the severe frostbite that temporarily left him unable to walk.

Some years later, a boating accident claimed the lives of both his father and his son. It was his son’s 14th birthday.

His response to West’s question was simple: “It’s who I am,” he said. “I’m a commercial fisherman. I was born this way.” He added that for him—and indeed, for many, many others—fishing was far more than just a job, and identifying as a fisherman implied a special connection to the ocean and encompassed a whole range of feelings and responsibilities that were not always visible or understandable to others.

“It’s an emotional thing as much as it is a way to make a living,” he said.

When the moderators asked him what prompted him to start writing poetry, Densmore named that emotional connection to the water—the intangible and invisible aspect of a fisherman’s life—as his muse.

Everywhere he looked, he said, he saw commercial fishermen being portrayed as “robbers and…rapers of the ocean.” Frustrated by being villainized—and seeing that characterization used to justify increasing regulation of the fishing industry—Densmore decided do something about it.

“People don’t know who commercial fishermen are, don’t know the emotional side, their connection to the ocean.” His poetry is a window into that world.

From Densmore, the moderators moved to Diane Wilson, another dyed-in-the-wool commercial fisherman whose efforts to defend fishermen and fisheries led her deep into the world of social and environmental activism.

In her quest to protect her native Gulf Coast Bay and draw attention to the pollution that had laid siege to the waters and the watermen who worked them, Wilson has launched legislative campaigns, political demonstrations and protests, and hunger strikes. She has sunk boats, climbed chemical towers, and been jailed more than 50 times for civil disobedience.

In addition to being a fourth-generation fisherwoman, an activist, and a mother of five, Wilson has written three books about her experiences and has been profiled in a number of national media projects. She is currently working on a fourth book, a fictional account of the end of Texas commercial fishermen.

She spoke about what it was like to be a woman in a world dominated by men, ultimately pointing to the fact that fishing can be an egalitarian industry: “Even when men cannot understand you being out there at all, they don’t care when you can fix the nets.”

And when Garrity-Blake asked Wilson why she got into activism in the first place, and what prompted her to become so radical in her work, Wilson’s rather poetic answer reflected a uniquely feminine, maternal perspective that seemed to speak to the largely local audience on several levels.

“This is why it’s important growing up in a fishing town and being here your whole life,” she said. “I can remember extremely clear, when I was probably…5 years old, and I could go down to the bay, and I could see the water. I saw what she looked like. It was a woman. The bay really is a woman, and she’s got a personality like a grandmother, and she was real, and she was there, and…she was alive.”

It was an image that stuck with her, a lesson she never forgot. “Knowing that this woman was in distress,” she said, “was what moved me.”

And if you’re wondering if Wilson regrets becoming an activist, the answer is no.

Though her work has gotten her in plenty of trouble and has cost her two marriages, a house, a boat, a job, and a lot of friends, Wilson’s answer to Garrity-Blake, when she asked Wilson if it had all been worth it to her personally, was resounding and unequivocal.

“Oh yeah,” she said. “I remember the day my [former husband] and I finally broke it, he said, ‘You know, I don’t like who you are,’ and I was just thinking, at that very same moment…I’ve never liked myself so much in my life.”

Between Densmore’s struggle to show the world the true identity of commercial fishermen and his heartbreaking portrait of their complex, emotional connection to the water, and Wilson’s inspiring story of seeing the soul of the bay and giving everything she had to protect it, it’s safe to say that, if one of Lynne Foster’s goals for the evening was to uplift and inspire the Hatteras fishing community, the event exceeded expectations.

As the applause for Wilson died down, West and Garrity-Blake began the next round of questions, directing them to the remaining two panelists, Robert Fritchey and Niaz Dorry.

Unlike Densmore and Wilson, Fritchey and Dorry were not born into commercial fishing families or even (in Fritchey’s case) into fishing communities, but both are accomplished and outspoken advocates for commercial fishermen and the fishing industry.

The tone of the discussion shifted a little when it got to them. The questions became less about who commercial fishermen are and what they are fighting for, and, instead, focused more on what’s happening to commercial fishing and what can be done to save it.

Fritchey spoke first, recounting how he, the son of a Pennsylvania dermatologist, went from completing a master’s degree in tropical medicine and medical parasitology, to working as a trammel-net fisherman in Louisiana, landing redfish from the deck of souped-up mudboat.

He talked about the controversy surrounding that fishery—a controversy that was fueled by a growing recreational fishing industry that demanded more access to the fishery’s resources and was exacerbated by media coverage that demonized the commercial faction.

Louisiana’s 1995 legislative net-ban, a watershed decision in the fishing world, put Fritchey out of business and became the subject of his influential book, “Wetland Riders.”

He effectively characterized the action as an unfair monopolization of public resources by private organizations, and he talked about how, through manipulation of words like “conservation” and “environmentalism,” the public had been led to believe the myth that commercial fishermen are, as Densmore put it earlier, “rapers of the ocean.”

Fritchey’s words no doubt fell on sympathetic ears, as North Carolina’s fishermen have seen red drum become gamefish and have been fighting net ban legislation for years—against the very same organizations that led the way in Texas and Louisiana, which are using the same manipulative tactics.

But Fritchey had hopeful words for the watermen in the audience.

“I’ll say this,” he said, when West brought up the similarities between the two fisheries. “Y’all are way more organized up here, and you’re in a whole lot better shape than Louisiana fishermen ever were.”

Fritchey’s emphasis on media misrepresentation of commercial fishing and the unfortunate impact of the collusion of politics and environmental science led smoothly to Niaz Dorry’s discussion of the difference between industrial fleet fishing operations and their small-scale counterparts—those independent operators, found in coastal communities all over the nation, that are slowly losing access to resources and being forced out of business.

Dorry is currently the coordinating director of the Northwest Atlantic Marine Alliance (NAMA), but she began her work protecting small-scale, traditional, and indigenous fisheries as a campaigner for Greenpeace.

Given Hatteras Island’s recent dealings with environmentalists and environmentalist causes, it would be understandable, forgivable even, if the mention of Greenpeace raised more than a few red flags in an audience full of Hatteras residents and fishermen, but Dorry’s work actually aligns perfectly with the interest of Hatteras Island’s fishermen, and her ideas are reflected in recent initiatives (such as Outer Banks Catch and Saltwater Connections) that have been started here in the interest of promoting and protecting our local fishermen.

“From the get-go,” Dorry said, explaining how she came to be one of the most influential advocates for small-scale fishing communities in the country, “one of the things that became really pretty clear to me, was that there was a difference between fishing and extracting marine animals.”

For Dorry, the solution to the problem of maintaining healthy fish stocks and healthy fishing communities is a simple one, and it’s right in front of us: small fleets, composed of independent operators who use diverse methods to harvest a variety of fish. That is the path to sustainable, environmentally sound fisheries.

In the end, “we have to make sure that who ends up catching our fish are our community-based fishermen.”

Dorry, as well as the other panelists, also called on the public to take an active role in this cause.

She essentially compared the current state of the fishing industry to that of the farming industry in the mid-20th century. Fishermen, like farmers, are faced with the choice between scaling-up their operations to the industrial level or losing their boats and their livelihood altogether—get big or get out.

To combat that approach, Dorry said that it is imperative for members of fishing communities—as well as the general public—to educate themselves about the provenance of their seafood, to understand the truth about commercial fishermen and the work they do, and to support local fishermen, not just by purchasing the fruits of their labor, but by speaking out about the issues they face.

It’s good advice, and as soon as the audience was done asking questions of the panelists, it was put to good use.

Volunteers served up scallop cakes and steamed shrimp (donated by the Wanchese Seafood Co.), fried Spanish mackerel (donated by Avon Seafood), and fried soft-shell crabs (donated by Nags Head-based fisherman Chad Hemilwright).

Everyone got a little taste of what it’s like to support local fishermen.

And it tasted good.

FOR MORE INFORMAITON:

For a related story on Day at the Docks with a slide show, go to http://islandfreepress.org/2012Archives/09.17.2012-DayAtTheDocks2012DrawsLargerCrowdThanEverToHonorIslandWatermen.html