In the depths of winter, when the battle between light and dark sways towards the night, when temperatures have plummeted to the lowest of lows, when ice begins to reform along coastal stretches far to the north, a most unexpected visitor arrives in North Carolina.

To be quite honest, you probably have never heard about them or seen them. This is not surprising, as they are something of a new comer to this Old North State. Their arrival is unceremonious and often cloaked by darkness. The odds of encountering one of these visitors are completely stacked against you. Their numbers are few and quite often spread thin.

Yet each year, for a couple of decades now, they appear as if out of nowhere, and materialize from the sea.

High pressure and low temperatures have coalesced to clear the night sky of the humidity driven haze that typically hangs in the air. The stars are incalculable this evening, glowing so brightly as to be seen above the two beams of my headlights bouncing over the sand as I drive the beach. Old live oak and red cedar stumps rise from the sand at the edge of the sea, the artifacts of island migration and the constant change that characterizes life on a sandbar – and very real threats to life and limb when navigating this beach at night by vehicle. This is not my first rodeo, however, having spent much of my life driving this very same stretch of sand along the Currituck Banks.

A dark shape catches my attention beyond my headlights. With all of the stumps around there are plenty of dark shapes to jump out at you, but this one is different. This one is moving. This one is crawling out of the ocean. I conclude that this is decidedly uncharacteristic behavior for a stump, even for this time of night, and come to a stop in order to get a better look. Hauling itself from the cold and wind churned waters of the Atlantic Ocean this evening is an adult harbor seal.

This is pretty new stuff. If you found yourself cocking your head to the side and thinking that you have never heard of such a thing, then rest assured this is for good reason. Thirty years ago, there were no seals on these beaches. In fact, when we look back into the primary sources of the annals of history, we find the record to be conspicuously empty of any mention of seals at all. It has been since only around the mid-1990s that these animals have begun making an annual appearance — and quite frankly, no one has a clue as to why. But, there is one person who is determined to find out.

Meet David Johnston of Duke University’s Marine Lab in Beaufort. Johnston has that sort of look you kind of expect from a biologist. A look that says, “I get paid to play outside, so I am genuinely happy, content with life, and I have the beard to prove it.” Come to think of it, that kind of sums up my look as well.

Normally you can find this guy being tossed around in a research vessel chugging its way through towering waves in the southern ocean heading toward Antarctica to study seals. At other times, his research takes him to slightly more ideal locations such as Australia or Hawaii. But the day that he called me up and asked me to meet with him to discuss a research project he had brewing inside his mind, several months before I happened upon this harbor seal now perfecting its yoga stretches on the half frozen beach in front of me, David Johnston was sitting in his office on Piver’s Island in Beaufort where he runs the Johnston Lab (not a coincidence in naming) and does time teaching marine bio grad students for Duke.

Sitting at a table before an impressive spread of flat screen TVs on the wall, all displaying one large continuous satellite image of a grey seal colony along the coast of New England, Johnston began discussing the need for getting to the bottom of why seals are starting to show up here. You see, if we were just finding harbor seals, which are common enough on the beaches north of New Jersey, this might be attributed to a rebounding population thanks to the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1976. Though harbor seals do make up the bulk of the seals we are seeing, it’s the other species, however, that are really beginning to raise red flags.

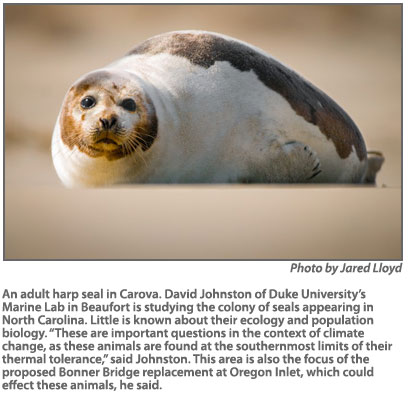

Mixed in with the harbor seals are basically every other species of seal found in the western Atlantic. Massive grey seals weighing in at 500 pounds are showing up in Kitty Hawk and Ocracoke. Harp seals and hooded seals, both species that live and die by the pack ice of the Arctic, are being found from Carova Beach to Cape Lookout. None of these should technically be here – especially the pack ice seals.

A few years back, I was working on a story about seals off the coast of North Carolina for a magazine when I received a tip from the N.C. Wildlife Resource Commission that fishermen were regularly reporting seals in Oregon Inlet that year – especially around one particular island. As of yet, no one had been able to make an official investigation into this and I was asked if it was something I would be interested in checking out. Naturally I jumped at the suggestion and did what any sane person would do: I slid my kayak into the hypothermia-inducing waters of February and paddled out into one of the world’s most dangerous inlets in search of seals. What I was to discover would ultimately change our understanding of seals in North Carolina.

Paddling out to the island in question, at first I saw nothing remarkable. Studying the shores from a distance with binoculars I only saw what I thought to be debris washed up from a recent nor’easter. When one of the logs got up and hauled itself back into the water however, I realized that there was more to this log.

What I had stumbled upon turned out to be a colony of adult seals – mostly harbor, but with a couple harp seals thrown in for good measure. I counted 37 adult seals hauled out on that beach, and in short order I had other seals popping up next to my kayak to get a better look at me.

This was not supposed to be happening. This is North Carolina, not Maine. Yet, here they were. And these were not the juveniles that we have come to expect. These were all mature seals, and they were literally everywhere.

Talking with Johnston about this in his office, he grinned from ear to ear. It was ultimately this discovery in 2011 that put Oregon Inlet on the map in terms of seals, and it was right where he wanted to get started.

“This feeding colony is the southernmost known in the Atlantic, and very little is known about the ecology and population biology of these animals. These are important questions in the context of climate change, as these animals are found at the southernmost limits of their thermal tolerance,” said Johnston. Furthermore, “This area is also the focus of upcoming construction which could impact these animals.”

The construction that Johnston was talking about was the proposed replacement of Bonner Bridge, which spans Oregon Inlet. This new version of the bridge is to be built right over top of the island that these seals are using. This population of seals is already being labeled as the most endangered in the world. Just what exactly the impact of such long term construction would have on these seals, nobody knows.

This study is still in its infancy, and will most likely take several years given the short window of time there is to work with. Next winter Johnston and a team of graduate students will start working with aerial drones, thermal imaging, remote cameras and video to begin intricately piecing together the puzzle of these seal’s use of the Oregon Inlet site.

This is ultimately where I come in, as the team’s photographer and videographer, and how I found myself sitting at Duke’s Marine Research Lab across from Johnston discussing my experience with seals on the Outer Banks and collaborating with one of the top minds in the field.

There is a certain degree of urgency to this whole thing. The situation in the north is changing quickly. Ice packs are changing. Fish populations are changing. Puffin chicks are starving to death because the parents can no longer find hake and herring – two species of fish incidentally that many seals depend upon. The ocean is warmer. Less salty. And God only knows what else. This is why when we see seals beginning to pop up on our coast, especially those that should be lounging around on ice flows, images of canaries in coal minds start dancing in the heads of researchers.

The ocean really is the last frontier for us. It is a world apart from ours. Species that call the oceans home, play by a different set of rules than we do on land, they are constrained by different forces. Theirs is a world kept secret from us, hidden beneath the waves of the sea, guarded by Poseidon. The story of these seals and why they have begun to show up along our beaches is one small part of this mystery. Hopefully it is a part that in the coming years we will be able to shed light upon before our actions as a society dictate it to be too late.

(Jared Lloyd is a professional wildlife photographer and nature writer. Growing up on the Outer Banks, Jared has spent much of his life exploring the barrier islands, pine savannahs, black water swamps and sounds of North Carolina. These days his photography and writing carry him all over the world from Africa to the Amazon, the Galapagos to Yellowstone, but the lure of the salt life along the coast keeps bringing him back to North Carolina. He lives in Beaufort with his wife and son for easy access to blue water and uninhabited islands. This article is provided by Coastal Review Online, an online news service covering North Carolina’s coast. For more news, features, and information about the coast, go to www.coastalreview.org.)