In honor of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse’s 150th anniversary, which will be formally celebrated on December 16, 2020, the Island Free Press will be featuring new and archived stories about the famous Hatteras Island landmark all week long. The following story was first published in August, 1999, from a special section of The Island Breeze on the move of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.)

The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse began its historic and controversial move out of harm’s way on June 17 at 3:05 p.m. in a steady downpour of rain.

The journey ended 23 days later on July 9 at 1:23 on a particularly hot and humid summer afternoon.

In between, thousands of people came to see the famous sentinel — before, during, and after the move of just over a half mile. Visitation reached a peak during the actual trip that the lighthouse took along steel tracks and down a specially prepared roadbed. The National Park Service estimated that 10,000 to 15,000 people a day visited the construction site. About 40,000 came to see the move over the July 4 weekend.

The National Park Service, after years of trying to control erosion and a decade of study, announced in 1989 that moving the 208-foot lighthouse 2,900 feet to the southwest was the best alternative to save it from the encroaching Atlantic Ocean.

However, it wasn’t until 1997 that $2 million was appropriated in the federal budget for the planning and design for the move. The following year, Congress appropriated $9.8 million for the move, and the contract was awarded to International Chimney, Corp. (ICC) of Buffalo, N.Y.

It took ICC more than six months to get the actual moving of the lighthouse underway in mid-June. The preparations for the historic journey turned out to be hard work.

Around the first of the year, the Cape Hatteras Light Station was closed to the public. The light station and the move corridor were closed off with orange fencing. By the end of January, the once quiet, seaside station was a construction site with piles of sand and gravel, dump trucks and front-end loaders, and construction materials piled everywhere.

In February, workmen began the monumental task of removing the lighthouse from its foundation. Workmen dug a trench around the light about six feet deep — right down to the yellow-pine timbers on which the foundation had rested for 129 years. A powerful system of pumps was used to pump water out of the excavation.

A diamond-tipped cable saw was used to make a razor thin cut at what was once ground level to separate the tower from its granite and mortar foundation. And then men worked almost around the clock for almost three months with muscle and hydraulic drills to remove the granite and mortar in large chunks. As the foundation was removed, it was replaced with bright orange shoring towers.

The task took longer than International Chimney officials expected. The builders of the lighthouse, they agreed, had done a fantastic job of putting the foundation together, and taking it apart was a larger challenge than anyone had planned. The move fell behind schedule.

Meanwhile, the light was turned off at the top of the tower on March 1, and the principal keeper’s and double keepers’ quarters were moved to the grounds of the new light station, where they were placed in the same relationship as they had been to the lighthouse and the sea.

On May 1, in between downpours from a northeaster, trucks poured 540 cubic yards of concrete to make a 60-by-60 foot mat that is four-feet thick for the lighthouse’s new foundation. The concrete is reinforced with 58 tons of rebar — epoxy-covered steel tubes.

By mid-May, the foundation removal had been finished and subcontractor Expert House Movers took over the move. For the next month, the movers worked on the final preparations.

The shoring towers were replaced by a grid of seven massive main beams — each 70 feet long and weighing 11 tons — and 12 smaller crossbeams installed underneath the lighthouse to serve as a temporary foundation during the move. The beams were fitted with 100 hydraulic jacks. The entire grid of beams formed a temporary foundation on which the lighthouse rested during the move.

The 100 jacks were deployed over a week’s time to lift the lighthouse 5.34 feet so that seven parallel “move” beams could be inserted to serve as a “track” for the move. The move beams were outfitted with rollers — 100 in all — that operated like the tread on an army tank. The hydraulic jacks rested on the rollers and acted as a suspension system to keep the lighthouse level during the move. The jacks were also divided into three zones to help control the stability of the tower.

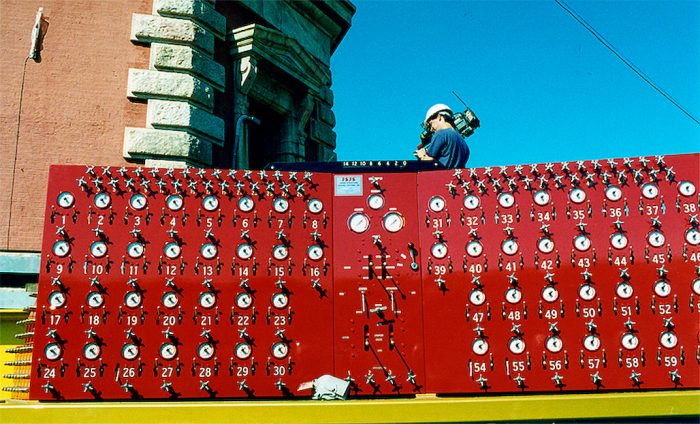

On the northeast side of the lighthouse, an operator controlled the unified jacking system at a very large, bright red board with 60 gauges. A computer screen above the board allowed the operator to monitor various instruments mounted to the lighthouse to indicate its stability during the lift and the move. The gauges on the board were designed to pick up any movement or tilt during the trip.

The lighthouse traveled over a mat of steel on top of a roadbed that had been specially prepared to handle the weight. The native soil was compacted, and 10,000 tons of stone were spread along the route.

A system of five longitudinal hydraulic jacks pushed the tower — very slowly, five feet at a time — along the tracks. Then the movers stopped and reset the entire system for another push. As they moved along, the steel mat was leapfrogged along with it — picked up and set out again in front of the tower.

Though the movers fell behind schedule during the foundation removal part of the project, they more than made up for it during the moving phase.

The actual move was expected to progress at about 25 to 100 feet a day and take up to 58 days. In reality, it took only 23 days and moved along at a rapid pace — 355 feet in one day and more than 200 most days. The increased speed was largely due to improvements in the method used to reset the hydraulic push jacks. The engineers replaced 12 bolts that had to be loosened and repositioned manually with one hydraulic clamp.

Once the lighthouse reached the concrete pad that is its new home, the process of jacking it up on the temporary foundation and the move beams was reversed.

Towers of oak cribbing were placed between the move beams. These cribbing towers were built up to jacks in the bottom of the steel beam temporary foundation. These cribbing towers and jacks were pressurized against the bottom of the lighthouse and temporary foundation. The pressure on the roll beams was released, and those beams and rollers were then removed. The lighthouse was then lowered again and sat on the cribbing towers below the steel temporary foundation.

The four-legged orange shoring towers were reassembled and placed under the lighthouse, replacing the oak cribbing towers. The shoring towers were then pressured up to the bottom of the lighthouse. The load weight was transferred back to the shoring towers and the steel move platform was removed.

The lighthouse sat on the shoring towers while workmen constructed a new foundation of especially dense and heavy bricks with mortar to replace the old granite foundation. As the brick foundation was completed, shoring towers were removed until the lighthouse load was again transferred totally to the new brick foundation.

Then, granite stones removed from around the lighthouse at ground level were replaced. The next phase at the construction site will include clean-up, restoration of utilities, and the construction of new parking and visitor facilities.

The light was expected to be turned back on around Labor Day, and the Park Service expects to reopen the lighthouse to the public next Memorial Day.