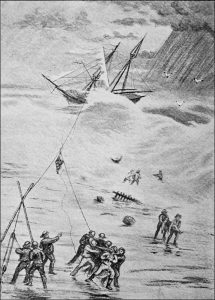

The story of a wrecked barge 115 years ago, at first glance, may not seem too exciting. This story, however, is not only engagingly interesting, but is also a somewhat complicated saga. On the negative side, it is of maritime lessons unlearned. On the positive side, it demonstrates, once again, the amazing tenacity of the United States Life-Saving Service on the Outer Banks, as well as how multiple stations worked together.

Prologue

The Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1907, p.35 begins to tell us the story: A steamship Katahdin was towing the large barge, Saxon, from Georgetown, South Carolina, bound for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The barge had a cargo of lumber and “She carried a crew of four-the master Frank Pilong; mate, Fred Lund; one seaman; and a cook. The names of the seaman and cook could not be ascertained.”

On the afternoon of October 12, 1907, when the two vessels were off the dreaded shoals of Cape Hatteras, they ran into rough weather. For several hours they wrestled with the turbulent ocean, but finally the Katahdin “parted their towline, the barge going ashore” says the Annual Report, two and a half miles south of the Gull Shoal station, and about four miles north of the Little Kinnakeet station on the outskirts of present-day Avon. A third station will also respond. The barge and cargo were a total loss and three of the crew were tragically and unnecessarily lost. The lone survivor tells the story.

The Ship

The Saxon was a 1,193-ton steamer built in Philadelphia in 1862. This was during the second year of the American Civil War. Forty-one years after being built, in that same iconic 1903 year that the Wright brothers made their famous flights, the huge, old, tired Saxon was unceremoniously cut down and repurposed as a highly utilitarian 555-ton barge.

The Fabric of America at the Time

By the early 1900s, America was still strictly divided geographically, politically, economically, and socially. Now, America had an amazing 193,000 miles of railroad tracks, its first oil wells were operating, and Andrew Carnegie had built the world’s largest steel mill.

The South was still trying to recuperate from the devastation of the war and the West was still wild. In the year 1903 alone, in addition to Wilbur and Orville’s fame, the first World Series game was played, Butch Cassidy left the States to live in South America, the “Buffalo Bill Wild West” show was touring mostly in the East, Geronimo was on the warpath, the wreck of the Old 97 inspired an iconic ballad, and John Dillinger was born. In all sections of America, transportation was still primarily by horse, carriage, railroads, boats, and ships.

The Saxon was simply in the midst of all of that. Towboats and barges had been common for many years then, and still are today.

Saxon’s Last Voyage

Facts gathered from the United States Life-Saving Service Annual Report tell us that “About 9 o’clock on the night of the disaster, when Surf man [sic] W.B. Miller, of the Little Kinnakeet lifesaving station, was covering the north patrol, he saw a white light seaward which he took to be the masthead light of a steamer standing in toward the beach,” but he determined there was no danger, and dismissed the sighting.

However, from the same report on page 35, it is learned that “Surfman A.V. Midgett, of the Little Kinnakeet station, who covered the north patrol from midnight to 3 a.m., also saw the masthead light of the steamer offshore.” Midgett did not dismiss the sighting. Instead, he continued his patrol on horseback in the direction of the lights. “Continuing, he discovered her [the wrecked Saxon] in the breakers some 250 yards from the beach. This was about 12:30 a.m. As he stood watching the vessel, he saw a rocket go up in the direction of Gull Shoal and knew that the crew of the Gull Shoal station had also discovered the wreck.”

What happened next was a typical reaction of all United States Life-Saving Service stations: Gull Shoal Station was the northern neighbor to Midgett’s Little Kinnakeet station, so he continued in that direction to assist. On his way, Midgett ran into three surfmen from Gull Shoal who informed him that keeper Capt. Zera G. Burrus of Gull Shoal had telephoned Chicamacomico, the next station farther north, to bring their beach apparatus cart.

Here, the Report itself becomes confusing and unclear. It says, at this point, “Midgett therefore turned back with the surf men [presumably coming back from Chicamacomico, so heading back south towards Gull Shoal and the Saxon wreck].” Upon arriving at the wreck, yet another surprise: Keeper Capt. Edward O. Hooper of Midgett’s own Little Kinnakeet station had deployed at the wreck with the entire crew, and had set up and begun rescue procedures.

“At this time,” says Captain Hooper in his testimony, “The stranded vessel could be seen about 200 yards offshore on the outer bar heading southward, the seas breaking over her, lumber washing overboard, sails lowered, and two side lights burning. A light could also be seen through the cabin window, but there were no signs of life on board.”

The Chicamacomico crew arrived with the beach apparatus. Two Lyle gun shots were fired and the second was spot on, but there was no response from the wreck. “While the perplexed lifesavers were grouped on the beach awaiting the coming of the surf boat, Mate Lund put in his appearance and soon cleared up the mysterious features of the night’s tragic event,” the Annual Report explained.

The Sole Survivor’s Account

When the towline broke, the Saxon was dangerously on her own. The Katahdin told the Saxon to try to make it alone to Hatteras, but the vessel was simply uncontrollable. Next, the Katahdin tried to reconnect a tow line, but two attempts were unsuccessful due to the storm conditions. First Mate Fred Lund recorded in the Annual Report, “The Katahdin then signaled us to anchor. I sounded and found a little over 3-1/2 fathoms of water. We let go our anchor, running out about 45 fathoms of chair, but it would not hold in the sea and current, and the Saxon dragged into the breakers and stranded.”

Mate Lund describes the resulting turmoil: nearly in a panic, the barge crew began to furiously offload the deck cargo, “but the seas were breaking over the barge and she was pounding so hard that the captain ordered the boat launched.” This was not only a classic mistake; it was a fatal one.

A Totally Avoidable Tragedy

From the earliest days of the Service, the lifesavers knew well that the number one cause of injury and death from shipwreck victims was their leaving the ship in a panic.

The lifesavers routinely conveyed this message in many ways. To expedite having the shipwreck crew successfully set up the Breeches Buoy, the United States Life-Saving Service published a booklet of instructions with text and diagrams printed which should be aboard all sailing vessels, and required of any that were insured. It was “Instructions To [sic] Mariners In Case Of Shipwreck: With Information Concerning The Life-saving [sic] Stations Upon the Coasts of the United States.” On page 7, warning shipwrecked victims NOT to try to save themselves, it says, with their italics for emphasis, … under no circumstances should they attempt to land through the surf in their own boats until the last hope of assistance from the shore has vanished.”

This is precisely what caused the avoidable Saxon loss of life. Lund continues with the launch of the small ship’s boat, “We had scarcely got away from the side of the vessel, however, when a sea came along and capsized us. I got clear and swam ashore; I do not know what became of the rest.” Drowning is what became of all three. Miraculously, after being washed back several time before reaching shore, Lund found himself abreast of a surfman’s half-way house where he took refuge. Exhausted, he spent the night and was discovered the next morning by the surfmen and taken to the station.

As per Standard Operating Procedures, an Investigating Officer of the Life-Saving Service after the event asked Keeper Burrus whether or not the Saxon crew could have been saved had they stayed aboard the wreck, he sternly replied, “Yes, we would have saved them, every one, without any trouble. The second shot put the line across the deck abaft* the mainmast, and the gear could have been rigged in a few minutes.”

Epilogue

The Katahdin survived. Four days after the wreck, and twelve miles away, the body of the cook was found by the Cape Hatteras Station crew. The body of the seaman was picked up by the Big Kinnakeet crew on the 18th, even farther away. The captain was never found. The Annual Report concludes, “a considerable portion of the lumber she carried was saved.”

* Archaic nautical term meaning: at or toward the stern (aft, after part or rear of ship)

These are excerpts from “Chapter 3 – Barge Saxon” of the yet-to-published sequel to the book “Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks: Dramatic Rescues and Fantastic Wrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic,” Globe Pequot Press. James D. Charlet also performs a variety of “live-theater” programs for “Keeper James Presentations” based on extracts from chapters in his book. He can be reached at keeperJamesLSS@gmail.com. See www.KeeperJames.com for much more information.