The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Fisheries Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced last month their intent to seek a change in status for the loggerhead sea turtles that are found in the waters off North Carolina and nest on coastal beaches.

The services proposed to change the turtle’s status from threatened to endangered, giving the animals increased protection.

The change could have far-reaching consequences on the Outer Banks, especially for fishermen.

The public has an opportunity to comment on the changes until June 14.

The services said last month that a comprehensive study by expert scientists determined that the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta ), formerly considered one species, may in fact be nine separate species or DPSs (distinct population segments). The loggerhead is currently listed under the Endangered Species Act as threatened.

The new determination would list two of the newly declared species as threatened and the other seven as endangered.

Among the turtles proposed for listing as endangered is the Northwest Atlantic Ocean loggerhead — the sea turtle that frequents the waters along the Outer Banks.

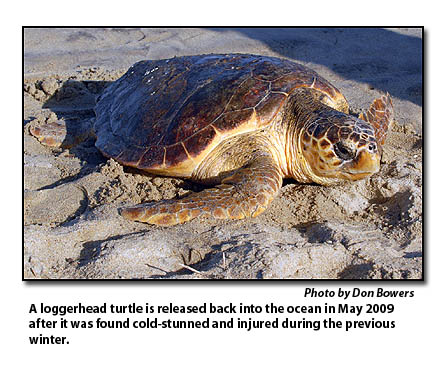

Loggerheads, along with green and Kemp’s ridley sea turtles, have been much in the news this past winter, as thousands have been stranded on shorelines along the Atlantic Ocean and eastern sounds. Unusually cold temperatures and high winds were blamed for causing the cold-stunned turtles to wash up on beaches, where some were rescued and many more died.

About 300 sea turtles have been stranded on Cape Hatteras National Seashore beaches since Dec. 1, and about 100 in one day on Portsmouth Island. Nineteen live cold-stunned turtles, mostly loggerheads, were rescued on Ocracoke’s ocean beaches in early February.

Prior to the new findings on the loggerhead, six species of sea turtles were identified worldwide and protected under the Endangered Species Act. Five of the six species — loggerheads, greens, leatherbacks, hawksbills, and the most endangered, the Kemp’s ridley — frequent the waters of the Outer Banks and nest on the beaches here.

Sea turtles are some of the most mysterious, fascinating, and well loved of ocean dwellers. They are among the largest living reptiles, and even though they spend almost their entire lives in the oceans of the world, they must come to the surface to breathe air and lumber up on sandy beaches to lay their eggs. Clumsy and slow on land, they are graceful swimmers in the water.

Loggerheads, the most common of the sea turtles found along North Carolina’s coast, are reddish brown in color and have large heads. They are medium- to large-sized, reaching up to 2 1/2 feet in length and weighing in at between 175 and 300 pounds as adults.

They swim far from their birthplaces, but upon reaching adulthood the females return to the beaches on which they were born to dig their nests. Nesting season on the Carolina coast is from May 1 through Aug. 31.

The turtles use their rear flippers to dig egg chambers where they lay from 100 to 180 ping-pong ball sized eggs, covering them up afterwards and returning to the sea. After approximately 60 days, the eggs, if undisturbed, hatch out and the nestlings scurry to the sea.

Sea turtle populations have been declining in recent years. Predation and natural weather events such as last winter’s unusually cold temperatures already take their toll, while such human-related impacts as water pollution, boat accidents, getting caught in fishing nets, and loss of nesting habitat from beach activity and development put them at great risk.

Raising their status on the Endangered Species List from threatened to endangered is meant to be a way to combat these harmful impacts.

The decision to re-examine loggerhead species began with a five-year study that ended in August of 2007. The services received petitions in 2007 from the Center for Biological Diversity and from Turtle Island Restoration Network requesting the new designations, and a formal status review was conducted in August of 2009. The report, filed by a Loggerhead Biological Review Team, was reviewed by nine scientists who were experts in the field and was described as “outstanding synthesis of the best available scientific information.”

Loggerheads and other sea turtles are already protected on the beaches of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore under current and proposed Park Service resource regulations.

However, many Outer Banks fishermen are concerned that should the loggerheads that frequent these waters be classified as endangered instead of threatened, their jobs will be imperiled.

Commercial fishermen are already struggling with a lawsuit filed against the state of North Carolina that has led the state’s Marine Fisheries Division to shorten the fishing season for flounder and reduce mesh size of the gill nets. Further restrictions could bring about an end to North Carolina’s gill netting fishery entirely.

The recommendation for reclassifying Northwest Atlantic Ocean loggerheads as endangered was based, in part, on declining nest sightings in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina.

Turtle expert Matthew Godfrey, who is with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, said that “based on the data we have, loggerhead nesting does not appear to be declining in North Carolina.”

In fact, a record number of turtles have nested on the beaches of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore for the past two years.

That would not necessarily exclude North Carolina from new rules and restrictions, however.

Alan Sutton, owner of Tradewinds Bait and Tackle on Ocracoke Island, said that “one of the reasons I wanted to move to Ocracoke was because of the wildlife, but now every time I hear the word it means more rules, closures, and loss of income. I’ve gotten so I don’t even want to hear about turtles or other wildlife.”

Ernie Foster, operator of North Carolina’s oldest charter fishing fleet, said when asked about the proposed reclassification, “I groan. It is a tragedy. As someone who has a long-term interest in the environment and environmental issues (as a former biology teacher), I find it very distressing. I see it as a way to use science to further certain people’s personal agendas, many of which are purely personal, and control other people.”

Ellen Gaskill, wife and mother of Ocracoke commercial fishermen James Barrie and Morty Gaskill, has read the entire 230- page Loggerhead Sea Turtle 2009 Status Report.

She says that the number of impacts on sea turtles listed in the report is enormous and includes, among other things, roads, hotels, houses, jetties, breakwaters, non-native vegetation, beach umbrellas, and walking on the beach. She believes that “they (the implementers of the Endangered Species Act) need to consider all these impacts and balance them. We would ask that other players (besides fishermen) in the game step up to the plate and change the way they operate in our coastal environment.”

Fisherman Gene Ballance says that he sees more loggerheads these days when he is out in his boat, perhaps because of warmer water temperatures in recent summer seasons. He emphasizes that he is concerned about loggerhead sea turtles, but wonders how scientists determine what is causing population declines or increases, and “if you help it one place, how do you know it will help it somewhere else?” He calls the Endangered Species Act “a good idea but a ridiculous law,” because “it puts it all on people who are trying to survive.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

If the Northwest Atlantic Ocean loggerhead sea turtles are indeed endangered, as the report says, then it is appropriate to classify them as such and take appropriate measures to ensure their survival. It is also important, however, to look at all the impacts and to make sure that one group of people does not bear a disproportionate share of the burden for ensuring their protection.

The information the services are seeking from public comments includes historical and current population trends and distribution of loggerheads, migratory behavior, current or planned activities that may adversely impact them, and ongoing efforts to protect them.

The 90-day public comment period ends on June 14, 2010. Submissions which state support or opposition without supporting information will be noted but will not be considered in making the determination. More information can be found online at http://www.regulations.gov.

Those wishing to comment can do so online or by faxing comments to 301-713-0376 or 904-731-3045. Comments can also be mailed to NMFS Attn: Loggerhead Proposed Listing Rule, Office of Protected Resources, NMFS 1315 East-West Highway, Room 13657, Silver Spring MD 20910 or USFWS National Sea Turtle Coordinator, USFWS, 7915 Baymeadows Way, Suite 200, Jacksonville FL 32256.