With its newly released report, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has dramatically increased the potential for wind energy from Delaware to Cape Hatteras.

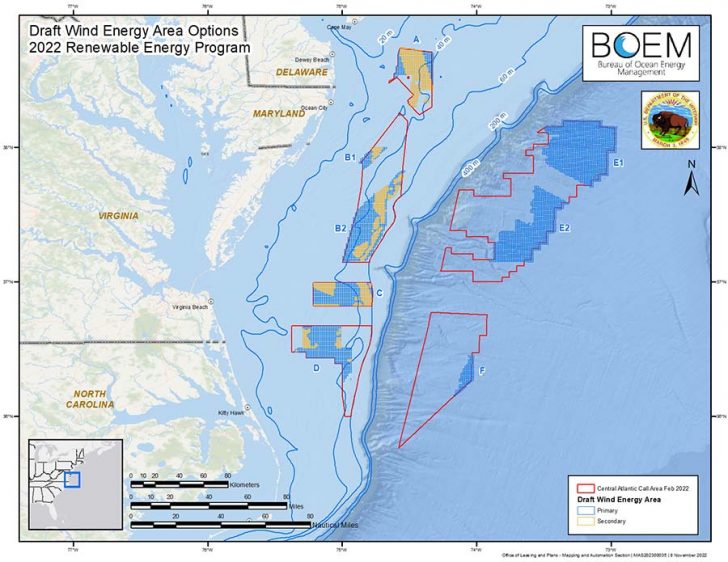

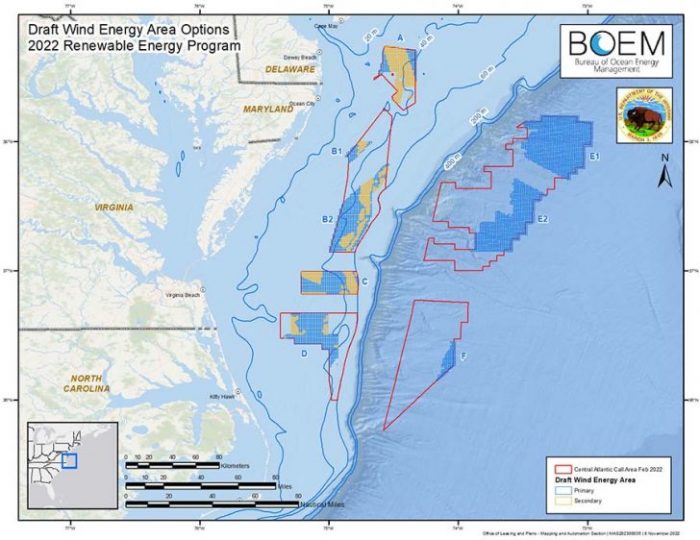

The six new areas to be considered are included in a Nov. 14 draft report titled Development of the Central Atlantic Wind Energy Areas. The draft concludes that in those areas, there are 1,747,026 acres that are considered suitable for the development of wind energy. The report is a draft or first pass at identifying areas for development — and there is now a 30-day public comment period that ends on Dec. 14.

“The Central Atlantic is one of several regions where wind energy development in offshore federal waters is being considered to support the Biden-Harris Administration’s goal of 30 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030,” the study notes in its introduction. The Wind Energy Areas (WEA) under consideration would certainly go a long way toward meeting that goal.

The report identifies six potential WEAs between Delaware and North Carolina, offering a preliminary assessment of whether they raise environmental concerns. Are they placed in migratory bird flyways or marine mammal migration routes? Are there Defense Department concerns or conflicts with ocean shipping and other factors? After reviewing the data on areas of concern, the potential WEAS are examined for the suitability of placing wind turbines.

It will be a number of years before there is ocean construction or wind energy captured from any of the proposed areas. After the public comment period closes, a final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) will be issued — usually at least six to nine months from the date the draft EIS is accepted. That will be followed by a series of more detailed analyses of the areas that may be available for lease.

BOEM will then conduct a lease auction. The winning company is required to produce a Construction and Operations Plan (COP) as well as an EIS specific to the area they will be developing.

Not included in the new report is the existing Kitty Hawk WEA, which was first proposed as an area for wind development in 2014. A recently posted timeline provided by Avangrid Renewables, the lease holder for the 122,405-acre Kitty Hawk WEA, has offshore construction beginning in 2027 with the first energy not transmitted until 2028.

Of the six proposed WEAs in the new report, two are in the waters off the North Carolina coast — Areas D and F.

Area D borders the Kitty Hawk WEA and extends south to a point about 35 miles east of Kill Devil Hills. On the north end, it’s about 85 miles from Norfolk.

The largest proposed WEA is designated D-1 and is 185,536 acres — 50% larger than the Kitty Hawk WEA. The D-1 site abuts the Kitty Hawk WEA. There is a much smaller secondary area, D-2, along the eastern side of the area that is 24,216 acres.

Area F is identified in the report to the east of area D. It is well offshore, 92 miles from Carova Beach and 123 miles from Norfolk. Although the distance from land will probably create some challenges, transmitting the energy seems realistic; the Kitty Hawk WEA will be available to link to any energy that is produced. Dominion Power is currently also developing a WEA immediately to the east of Norfolk as well.

The challenge to wind energy here is the depths involved. The offshore areas currently being developed along the coast are in waters as deep as 45 meters (148’). In those relatively shallow waters, turbine platforms rest on a monopole — a large, hollow metal tube that is driven into the seabed. To date, 45 meters is the maximum depth of monopole construction, although there is research being done that would take that depth to 65 meters (213’). The depth found in Area F far exceed any use of a monopole and if and when the area is developed, the turbines will likely be on floating platforms.

“Floating platforms in the deeper ocean are nothing new,” Dr. Reide Corbett, Dean of the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), told the Voice. “The oil and gas industry has been doing it for years.”

However, for the offshore wind industry, floating platforms are still being developed as a viable construction method, and according to Corbett, the depths indicated in the BOEM report appear to be deeper than anything currently in operation.

Although it may take a while for power to be generated from Area F, Corbett is confident it can be done. “With a new need comes innovation, so if we can imagine it, engineers will find a way,” he wrote in an email.

The deep water of Area F could offer possibilities for additional energy production. George Bonner, Director of the Renewable Ocean Energy Program at CSI, was in Spain for the International Energy Conference in October.

CSI is one of the leading programs in the nation in developing ocean energy. With the Gulf Stream passing closer to the Outer Banks at Cape Hatteras than any other place in North America, the Renewable Ocean Energy Program has become a leader in capturing energy from ocean currents.

While at the conference, Bonner saw that European offshore wind was being paired with other renewable energies — solar and wave energy. And he believes that is a concept that should be explored.

“We think there’s an opportunity for marine energy to compliment offshore wind, and we would like to