Shoaling at Rodanthe Harbor Emergency Channel Generates Concern at Waterways Commission Meeting

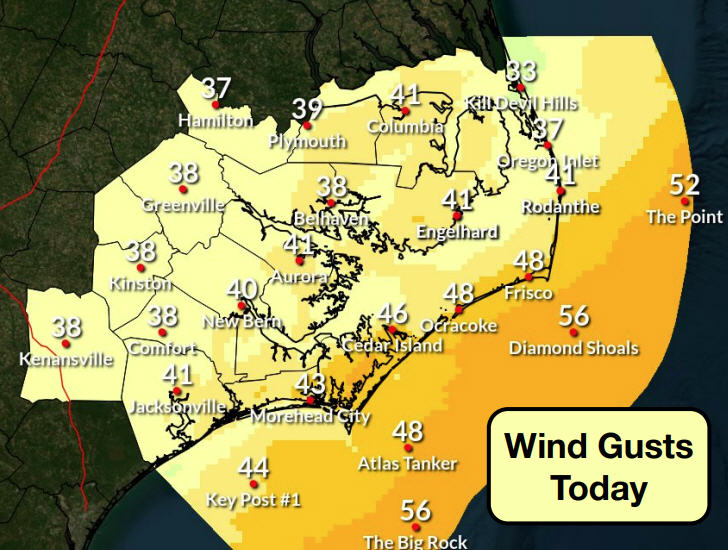

With the Rodanthe Harbor emergency ferry channel dangerously shoaled two weeks from the start of hurricane season, members of the Dare County Waterways Commission on Monday expressed alarm that there are no funds or immediate plans to clear the sand from the water route that would be needed if access to N.C. Highway 12 was cut off.

“This is for if something terrible happens,” Commission Vice-Chair Ernie Foster said at the meeting in the Dare County Administration Building in Manteo. “Quite literally, if something happens at the bridge right now, we’re doomed?”

It is essential that the channel linking Rodanthe and Stumpy Point harbors is navigable for emergency ferries to provide transportation backup for Hatteras and Ocracoke islands. The route has been put into service in recent years during power outages, and bridge and road closures.

The same area near the end of the channel in Rodanthe had been dredged by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers last summer, when about 3,000 cubic yards of sand were removed. A recent survey, however, revealed a return of the problem, with some sections having just 4- to 6-foot of water.

The complication now is that the Corps does not have funds or a dredge available to do the job, said Roger Bullock, Chief of Navigation for the Corps’ Wilmington district.

“We’re going to do a survey next week,” he told commissioners. “We don’t have a vessel here now that can dredge it.”

The Snell, the Corps’ most agile and versatile dredge, did the work in July 2018, but it is expected to be committed on the Gulf Coast until 2020, Bullock said.

From the March 29 survey, he said, it was estimated that 3,378 cubic yards of sand would need to be removed to obtain a depth of 6 feet, and 13,916 cubic yards for a depth of 8 feet. There is also a concern about remaining capacity for dredged material in the disposal site at the end of the channel.

Bullock said once the new survey is completed, the Corps will be better able to help the state and county devise a solution, which could include loading the material on a barge and hauling it off. An existing agreement would allow the Corps to accept state or county funds for a sub-contractor. If need be, he added, the Corps likely would be able to secure a permit quickly for “when there’s a dire emergency (and) you’ve got to get something going.”

“We just don’t want to get in the position where something happens and the channel is unusable,” said commissioner Danny Couch.

Meanwhile, another project is close to starting at South Dock on the north end of Ocracoke Island, with about 100 loads of material planned to be barged in at the end of June, said Lance Winslow, environmental supervisor with the state Ferry Division.

“We just have to make sure they don’t impede the ferry route, or even the channel there,” he said.

With the area around the ferry basin dock threatened by erosion, the National Park Service, which owns the land, granted an emergency special use permit to the state to replace the sheet pile wall and rebuild the dune to protect the ferry channel.

Winslow said the 120-day project is scheduled to start the week after July 4th. The state is also working with the Park Service on designs for groins or jetties that would provide a long-term solution to the erosion, Winslow said.

In a brief presentation later in the meeting, National Park Service Outer Banks Group Superintendent David Hallac told the panel that conditions – for unclear reasons – have gotten dramatically worse in the last year near South Dock.

“The water rips out of here at 6 knots,” he said, pointing to an image of the channel on the edge of Pamlico Sound. “The north end of this island is eroding extremely rapidly. It’s a game-changer.”

Ramp 59, just south of the ferry dock, also has not escaped losses, Hallac said. “There is no ramp,” he said, as he clicked through photographs of ocean surf flowing beyond the line of vegetation into the marsh. “There’s no place to drive; there’s no place to walk. There’s very, very dramatic change happening here. It’s going to get worse.”

But in relative terms, erosion in Cape Hatteras National Seashore may be most shocking on Hatteras Island, where the southern-most tip has lost 1.8 miles, or about 340 acres, since 1993. At the rate it has been eroding, the state-owned Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum and the Hatteras ferry docks could eventually be threatened.

Members of the Waterways Commission attribute the loss of Hatteras Spit, also known locally as Pole Road, to increased shoaling in Hatteras Inlet, but have yet to hear of any realistic way to restore it, or even stop its progress.

Surprisingly, Hallac offered encouragement to commissioners to seek expert advice from coastal scientists about potential restoration of the spit– for the sake of the birds.

“Can we build it back? Yes, we can build it back,” he said. “National parks are not spoil disposal sites . . . but we’re very interested in looking at ways to build up habitat at the end of Hatteras Island.”

It’s not just the spit that needs help, responded Waterways Commission chair Steve “Creature” Coulter, a Hatteras charter boat captain. The old spoil deposit site known as “DOT Island” also needs to be rebuilt, he said.

“Personally, I think that’s what kept Hatteras Inlet stable,” he said.

Other commission members in attendance were vice-chair Ernie Foster, Fletcher Willey, Danny Couch, Natalie Kavanaugh and Michael Flynn. Member Jeff Oden was absent.

Although it is likely that the state will soon allow DOT Island to be used again as a disposal area for up to 25 acres of material, discussion about restoration of the spit does not seem to have moved beyond the need for extraordinary amounts of sand and money.

“My strong suggestion is bring more science to the table,” Hallac said, especially oceanographers and coastal geologists who understand inlet dynamics. “Before you pump a lot of sand there, I’d want to know if it’s a good investment.”

Hallac said the Park Service would also be open to accepting dredged material at another severely eroded area along Roanoke Sound in Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. The county is currently working with consultant Ken Willson with Wilmington-based Aptim Coastal Planning & Engineering of North Carolina Inc. on locating a disposal site to use for the planned Manteo channel project. Shoaling in the channel has prevented the state-owned representative 16th century sailing ship Elizabeth II from leaving Manteo harbor for its annual maintenance, which was last done in early 2016.

In a discussion with Willson, who called in to the meeting, he said that the area Hallac is referring to would require pumping the sand along the shoreline for 3.5 miles from the dredge.

“It might be cost-prohibitive with the budget we have,” Willson said.

An alternative that would instead truck the sand was suggested, but Hallac said that would not be possible.

Willson said that other disposal sites were still being considered, including areas near the Elizabethan Gardens, CVS in Manteo, or on property owned by relatives of the late Andy Griffith, who had lived on Roanoke Island.

The state allocated about $2 million last year for the project. Willson, who was hired by Dare County to handle the permitting, said the process has been “straightforward.” But progress is being held up by the disposal issue, he said, and it’s probably not feasible that it can be resolved in time to meet the next dredge window.

“We’re looking at starting in Nov. 2020 instead of Nov. 2019,” Willson said.

The disposal concern was also addressed by Coley Cordeiro, coastal infrastructure program manager with North Carolina Division of Water Resources, who gave a presentation on shallow draft navigation issues. Of most interest to the panel was an update on the state’s new effort to manage dredge material disposal sites. The first step, she said, was to map all the disposal areas in the state, whether state, federal, local or private.

“The map is operational now,” Cordeiro told commissioners. The state intends to eventually make it available for users to access online, she added.

Inadequate disposal areas for dredged material – whether overfilled or eroding sites or nonexistent or poorly located sites – has been a growing problem statewide for years. But when the Corps of Engineers restricted access in 2017 to its disposal areas, the problem became a full-blown crisis.

Cordeiro said that the proposed plan also would document current capacity, current needs and current capacity needs of disposal areas. The scoping project, which will include consultation with the Corps, is the next step in what is expected to be a 2-5 year process, she said.

“There are several state agencies that are involved in this situation,” she said. “I always say, you can’t have a navigation project without a disposal site.”

No money because it’s going to fund this ridiculous overkill bridge in Rodanthe that will be 25 feet in the air, just to please Communist Environmentalists who, if they had their way, would force all humans off Hatteras Island.