With all the attention that sharks are getting this summer, snakes have been able to slither under the radar as the most sensationalized animal threatening human existence. Usually this time of year, we hear all about the “copper-mouthed, water-headed rattlers” aggressively chasing after people.

During my years as a park ranger, I once received a phone call from an excited neighbor screaming in a high-pitched voice about “a cobra, or might even be a black mamba” that was in their yard. I laughed and told them not to worry, that it was a harmless hognose snake that will mimic a cobra and scare the heebee-jeebies out of you. They were not happy with that answer, and I had to go to their house and relocate the snake.

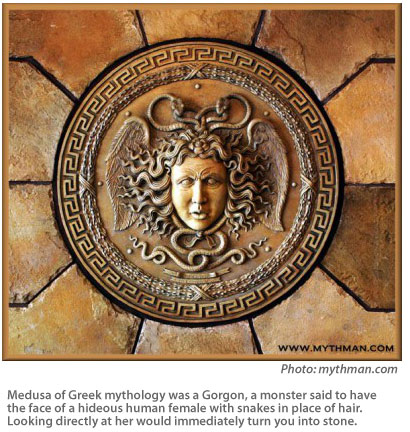

Those with ophidiophobia, the fear of snakes, are wary during the warm-weather months when these cold-blooded reptiles are much more active and moving about. Venomous or not, most people just don’t like snakes. Snakes have never been able to overcome their depiction in the Bible as Satan in the form of a snake that convinces Eve to take a bite out of that apple and thus, introduces sin into the world. The Greek story about Medusa, the woman with snakes growing out of her head who could turn people into stone with merely her gaze, didn’t help either.

In North Carolina, there are 37 species of these legless reptiles, of which six are venomous and can be found somewhere along our coastal plain. Five of the six are pit vipers — copperheads, water moccasins (also called cottonmouths) and canebrake, pigmy and eastern diamondback rattlesnakes. Just reading the names will cause anxiety in some people.

Pit vipers are so named because of a small depression, or pit, between the eye and nostrils. This pit contains a sensory organ, or thermoreceptor, that can detect the body heat of warm-blooded prey mammals such as rats and mice.

The sixth venomous snake, the coral snake, is in the same family as cobras and mambas and is referred to by some as the American cobra.

Technically, all of these snakes are venomous, not poisonous. They inject, like a hypodermic needle, their venom through their fangs. Poisonous plants and animals, such as some types of frogs and the berries of the Virginia creeper vine, transmit their poison though touch or by being consumed.

I’m not exactly sure what makes people so afraid of snakes. I don’t think it is one specific characteristic, but rather the totality of many. Right off the bat, many folks think that snakes are slimy. Not true. The scaly outer layer on their body is dry, smooth and has a glossy sheen that may give the impression that it is wet and slimy.

Then there is that forked tongue flicking in and out of their mouths that gives some people the creeps. This is just a snake’s way of smelling tiny chemicals in the air or ground and delivering them into the mouth to be analyzed by what is called the vomeronasal system located near the nasal cavity. Here, messages are sent to the brain to help the snake follow prey, find a mate and avoid predators. The tongue is split with a left and a right side giving the snake a sense of direction based on the chemical concentration levels detected by each side.

The serpentine movement of snakes as they wiggle about can also be unnerving to some. Snakes use box-shaped ventral scales along their belly to grab the ground for traction much like a tire. They have a number of propulsion styles that allow them to adapt to changing ground conditions. Even without legs, they are good climbers.

Then there are the broad triangular heads of the pit vipers with their elliptical eyes that create a facial demeanor some associate with evil. These cat-like eyes are important for hunting at night and accurately tracking the movements and distances of prey.

Finally, there is the fear of those double-barrel, retractable fangs dripping with venom, sinking into your flesh and releasing its consequences. A Bible quote, “And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people …” has really left an impression. As a rule, snakes will bite humans only as a last resort to protect themselves. They usually slink away and try to avoid confrontations. When provoked, they will defend themselves in a manner that is perceived as aggression.

Because of their excellent camouflage that seamlessly conceals them in their natural surroundings, many snake bites occur when people step on them or reach into areas where they cannot see. Most venomous snake bites, however, occur when people try to touch, handle or grab hold of danger waiting to happen. Darwin Award candidates displaying such bravado can be rewarded with a trip to the emergency room. Just ask this guy, who showed off by kissing a water moccasin.

The venom of pit vipers is similar to saliva and contains proteins and enzymes that are hemotoxic and do damage to tissue and blood. A bite can produce swelling, pain, weakness, nausea and inhibit the ability of blood to coagulate. Coral snake venom, on the other hand, is a neurotoxin and affects the nervous system, causing paralysis and breathing difficulty.

When hunting, the bite and venom of these snakes is used to immobilize and digest their prey. When they bite as a defensive measure, such as during interactions with humans, there is a good possibility that very little or no venom is released from the fangs. These “dry bites” are used on non-prey animals as a way to defend themselves while conserving their venom. This isn’t to suggest that a harassed and agitated snake won’t bite repeatedly and with a full complement of venom.

All of these distinctive traits of snakes that give people the willies are simply amazing adaptations that allow snakes to make their niche in this world.

In North Carolina, the copperhead and timber rattler can be found throughout the state in a variety of habitats. The water moccasin and pigmy rattler are mainly found in the eastern part of the state and the eastern diamondback rattler and coral snake are in the southeast coastal plain.

Copperheads are the species we are most likely to encounter and they account for the majority of reported snake bites. They are quite social and like to hang with other copperheads. Young copperheads are recognized by the yellow tip of their tails which they will jiggle as a lure to draw in prey such as frogs. Adults have a preference for rodents but will also climb shrubs and trees looking for cicadas.

The water moccasin, as its name implies, spends a lot of time at night in aquatic habitats such as marshes, streams and ditches, where it waits to ambush frogs and fish. The water lowers their body temperature, which is why they can be found basking in warm, sunny spots for extended periods during the day. It is also known as the cottonmouth snake because of its defensive posture of opening its mouth widely, exposing the white fleshy interior. They can grow to more than four feet long.

Of the rattlesnakes, the Carolina pigmy is the smallest. It is a slim snake found in sandy longleaf pine forests and is only a little more than two feet when fully grown. The rattle of the pigmy is tiny and hard to see. When agitated, the sound of the rattle doesn’t travel far and sounds more like the buzzing of an insect. Because of loss of this unique habitat, the pigmy is a species of special concern in North Carolina.

The timber or canebrake rattlesnake is a brute of a snake growing up to six feet in length and is also a state species of concern. This shy snake is reluctant to engage its rattle until danger is imminent. Its scientific name, Crotalus horridus, identifies it as a dreadful rattle.

Diamondbacks are without a doubt the big beast of the rattlesnake world. Some individuals have been documented at almost eight feet in length and weighing in at 30 pounds. Anyone seeing this bruiser unexpectedly along a forest trail will surely pass out on the spot or be unable to run because of uncontrollable body spasms. Those who remain conscious will be mesmerized by the gorgeous dark diamond pattern against its sand-colored scales.

While their main prey is rabbits, they will also target rats, squirrels and birds. North Carolina is the extreme northern range of these snakes, which are listed as a state endangered species, rare and difficult to find in the wild.

All pit vipers have a rugged look, but the eastern coral snake is svelte and elegant looking with a round head and eye pupils. Its striking Halloween colors of black, yellow and red bands alternately circle the length of its body. The non-venomous scarlet kingsnake closely resembles, but should not be confused with, the coral snake. One of the clever rhymes to help identify which one is venomous goes like this, “Red touch yellow, kills a fellow; red touch black, venom lack.”

Somewhat of a recluse, this snake spends most of its time burrowed under decaying forest litter and loose soils. It ventures out at twilight and dawn to seek out prey such as other snakes and lizards. Because of their short, fixed fangs, they need to hang on and chew a little bit for the venom to take effect.

I cringe when I hear people say “the only good snake is a dead snake,” or when they try to rationalize the existence of some snakes, and thus, the condemnation of other snake species by saying, “at least it’s one of the good snakes.” All snakes, venomous or not, are good snakes.

While a lot of cultural history casts snakes in a negative light, there is plenty of history touting their virtue. They have long been symbols of wisdom, fertility and a sign of immortality because of their “rebirth” after each shedding. As a sign of healing, they are prominently featured in the Rod of Asclepius, a logo used by many health organizations throughout the world. Look at the Star of Life, a symbol of emergency medical services, and there you will see a snake. Today, their venom has a number of medical uses including treating cancer, stroke and Alzheimer’s disease.

A great place to learn more about these magnificent creatures is at the N.C. Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores in Carteret County. The herpetologist on staff, Fred Boyce, is a wealth of knowledge when it comes to snakes. Boyce grew up surrounded by his older brother’s snake collection. His childhood playmate and friend was a big black rat snake named Atlas. If anyone can talk you off the ledge of snake fear, it’s Boyce.

When asked how people develop their fear of snakes, Boyce replied, “I have no doubt in my own mind that the common fear of snakes is an acquired, learned behavior that has very little or nothing to do with the actual snakes themselves. Once you actually see a venomous snake, you’re out of danger and can observe it safely.”

The sight of snakes actually brings me comfort – comfort in the knowledge there is natural habitat to support their existence. If there is habitat for the snake, there is habitat for a diversity of other wildlife as well. Wildlife deserves our respect and right to existence, no matter what form it takes.

(This article is provided by Coastal Review Online, an online news service covering North Carolina’s coast. For more news, features, and information about the coast, go to www.coastalreview.org.)