Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

Second of three parts

It happened about 10 weeks before the second of Walter Raleigh’s three expeditions to establish an English colony on the North American continent arrived at Ocracoke Inlet in 1585. The expedition of seven ships was led by Raleigh’s cousin, 43-year-old Sir Richard Grenville aboard his flagship Tiger.

In the middle of the afternoon on April 19 in the Algonquian towns along the Pamlico, the sky grew dark, birds and beasts became eerily silent, and people trembled in fear. A rare hybrid solar eclipse was spreading across North America. The 25-year-old mathematician, expedition scientist, ethnographer and Algonquian translator Thomas Harriot was later told by the Native Americans that the eclipse “unto them appeared very terrible.” The event seemed to portend an ominous sign.

———

Describing the next leg of the exploration of Pamlico Sound after visiting Pomeiooc the journal of the flagship Tiger was succinct: “The 13. (July 13) we passed by water to Aquascogoc.” More than that surely transpired.

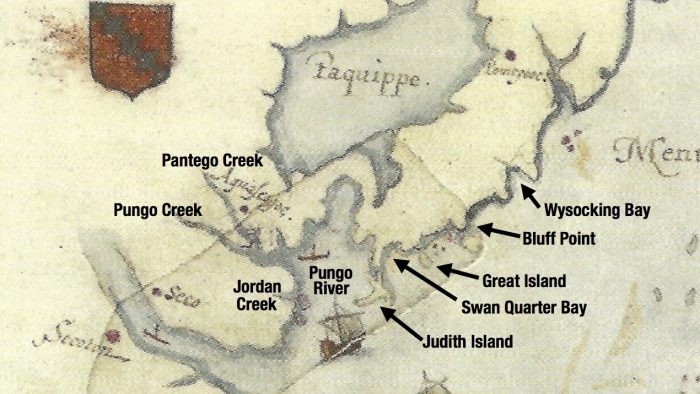

The Algonquian town of Aquascogoc, according to the map “La Virginea Pars” by expedition surveyor and artist John White, was located on the east bank of today’s Pungo Creek, a few miles north of Belhaven. The distance from Pomeiooc to Aquascogoc was roughly 50 miles, a lengthy trip in small boats that likely took two days to travel.

As the motley Elizabethan flotilla of Grenville’s London ferry boat, future governor of the Roanoke Island colony Ralph Lane’s Puerto Rican pinnace and the two ships’ boats were rowed or sailed westward, White, Harriot and their assistants began constantly taking soundings and bearings, estimating distances and noting the locations of points of land, bays and islands, and carefully converting the data to sectional sheets or small maps even while the boats pitched and rolled on gentle swells.

It was imperative that the surveyors maintain a constant proportion or scale — not a simple task while underway using 16th century technology. Keeping the paper dry was another challenge and periodic rain showers may have prevented some parts of the shoreline to be accurately recorded. But White’s watercolor rendering of the southern shoreline of today’s Hyde County reflects his best work.

We are able to recognize nearly all of the prominent geographic features the Elizabethans observed 435 years ago. The shape of Long Point appears as the first prominent peninsula passed by the explorers after weighing anchor in Far Creek and rounding Gibbs Shoal.

Wysocking Bay is likely the next major geographic feature they passed and White’s map matches well with today’s charts of the bay framed on the northeast and southwest by Long Point and Benson’s Point. Continuing their southwestward journey, the next prominent feature is Bluff Point. South of the point on White’s map is what seems to be a large island or peninsula connected to the mainland by a narrow isthmus.

This is where we encounter what was once a mystery—what lay beneath a small patch of similarly made paper and color palette fixed onto the final “La Virginea Pars” map, presumably by White. The reason for the patch had escaped the scrutiny of the greatest Roanoke Voyages scholars until eight years ago.

This writer had something to do with the discovery when his initial discussions with members of the First Colony Foundation regarding the accuracy of White’s map and its positions of Algonquian towns along the Pamlico eventually led them to contact experts at the British Museum. By examining the map using noninvasive infrared radiation, scientific conservators and curators in London were able to peer beneath the patch and see White’s initial graphite line drawing.

At the time, the greatest public interest (bordering on near hysteria) concerned a second patch that appeared to cover the symbol of a fort and potentially the destination and resettlement of the Lost Colony at the western end of Albemarle Sound. That is not our interest here; ours is why White’s painted patch depicted Bluff Point as a large island—larger, for example, than Great Island to the west that survives to this day.

The British Museum’s infrared reflectogram appears to answer the question. White’s graphite underdrawing seems to show, rather than a large island, an indistinct shape of either a small island or shoal off a more well-defined Bluff Point. The artist, after he had returned to England, may have been confused by data provided by Harriot or a missing sectional chart and then altered the original painting. Nevertheless, what caused White to paint the nonexistent island over the patch will remain a mystery.

The next familiar landmark appearing on White’s map as we and the Elizabethan explorers make our way westward is Great Island, just as it exists today southeast of Swan Quarter.

By the time Grenville’s party reached the lower part of Swan Quarter Bay, they had traveled approximately 25 miles — a full and tiring day in open boats, especially if they were being rowed. It was time for them to find an anchorage for the night. Few places are better for that at the mouth of the Pamlico River than Deep Cove below Judith Island.

For anyone who rides the Swan Quarter ferry to Ocracoke, Judith Island lies just off the ferry’s starboard side soon after departing the terminal.

The similarity between White’s 1585 map of the boot-like shape of land west of Swan Quarter Bay and the present-day complex of Judith Marsh, Judith Island and Swan Quarter Island is unmistakable. Deep Cove would have made an excellent protected anchorage (from waves, not mosquitoes) for the Elizabethans, just as it has on numerous occasions for this writer.

We can speculate that most of the following day, Wednesday, July 14, the explorers encountered poor weather. There was no journal entry for that day and White’s rendering of the Pungo River is badly distorted, indicating that it must have been difficult to take accurate bearings or to even see the shape of the river. White’s Pungo River is too wide and almost looks like a large bay of the Pamlico Sound rather than a southward flowing tributary of the Pamlico River.

Although it is angled northward and not eastward as it should be, the right-hand bend of the upper Pungo appears as an extension of the river pointing toward Lake Mattamuskeet. Other geographic features are more easily recognized. Both Broad Creek and Pantego Creek are depicted on White’s map, as is today’s Jordan Creek in its relative location about halfway down Pungo River on the west bank.

Manteo’s participation at this point is evermore assured because the Englishmen probably would have never found Aquascogoc without him. Neither would have the Roanoke Voyages historian David Quinn, whose analysis of the town’s location places it in the far eastern end of the Pungo River near present-day Scranton.

Comparing White’s underdrawing beneath the watercolor patch, it appears that the artist may have moved the symbol for Aquascogoc farther north on Pantego Creek, although this is only conjecture. The highest elevation of land along the creek, where the town would have been most likely located, is about 0.8 miles east of the present-day town of Pantego or 3.5 miles north of Belhaven.

White seems to have made no drawings or paintings of the town of Aquascogoc or its people unless the images were lost during the Lane colony’s hasty departure from Roanoke Island in June 1586. There are differing opinions as to whether White remained on Roanoke Island with Harriot or returned to England with Grenville in September 1585. Nor do we know how many families lived at Aquascogoc or whether it was palisaded or an open plan. But we do know for certain that they visited the enigmatic town because of what happened two days later.

On June 15, 1585, Grenville’s expedition traveled farther up the Pamlico River to the town of Secotan, the primary objective of their trip. The town was considered the chief settlement of the Secotan nation, which likely included a confederation with the “kings” of Aquascogoc and Pomeiooc. The Secotans may have considered Wococon, or Ocracoke, to be part of their territory, too.

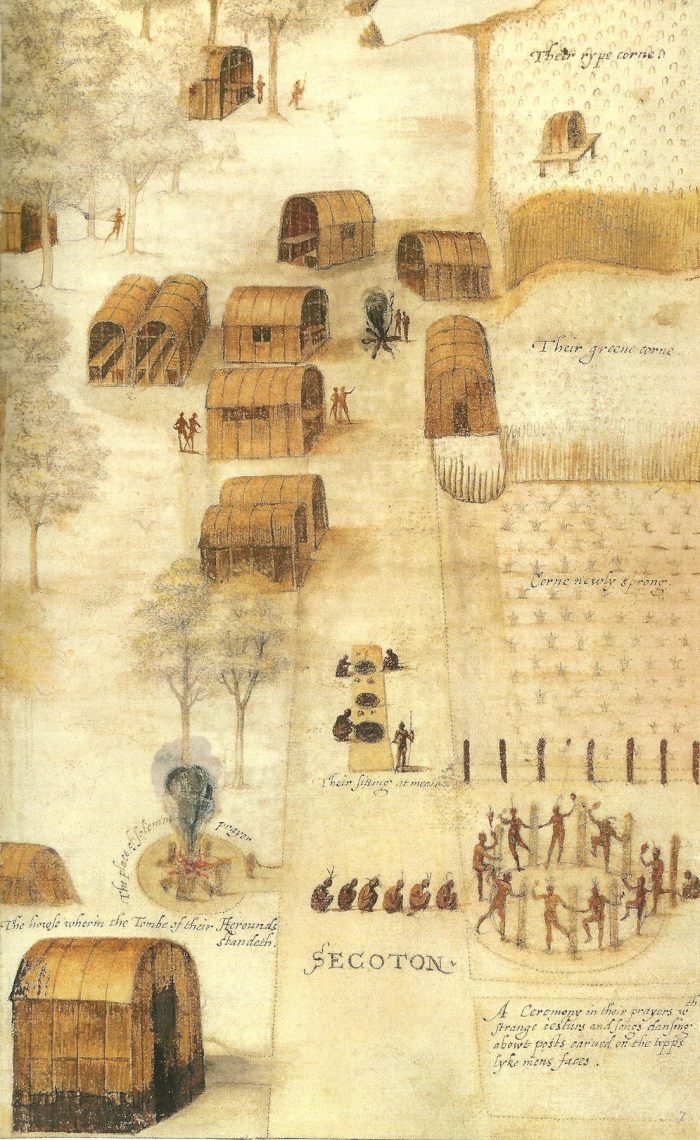

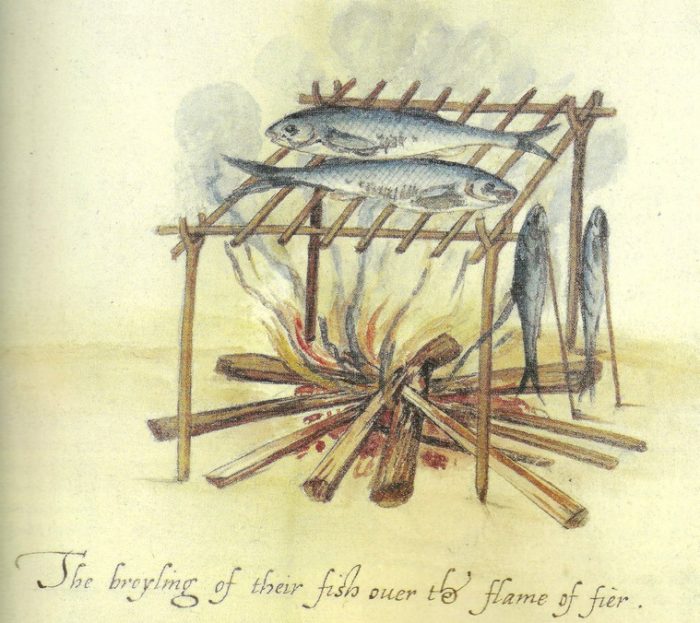

Secotan is historically significant because it is widely accepted that White created at least eight of his most iconic images there. For lack of their own original, site-specific illustrations, many of White’s Secotan paintings and their reproductions today are used in visitor’s centers and museums from Jamestown to Plymouth Rock, and elsewhere, to represent Atlantic coast Native American culture during the contact period.

What is far less agreed upon and far more controversial is where Secotan was located. This is an unsolved mystery that is, arguably, as important as the fate of the Lost Colony because of White’s paintings.

It should not be a mystery at all. Numerous sources of information, as well as physical evidence, point to the west bank of today’s Bath Creek as the probable location of Secotan and not on Pungo River or south of the Pamlico River, as some scholars have suggested.

John White is partly to blame for the confusion. The badly distorted shape of the Pungo River on his “La Virginea Pars” map has caused some historians not personally familiar with the waters to lose their way. Significantly confounding the issue, on the same map White labeled “Secotan” on the south side of the Pamlico River and “Seco” directly across the river on the north side.

First, irrespective of archaeological surveys, let’s rule out Pungo River as the home of Secotan. In 1584 at Roanoke Island, the Native Americans briefed captains Arthur Barlowe and Philip Amadas, who led Raleigh’s first expedition in 1584, of the region’s geography and towns, including the various “kings” who ruled them. “Towards the Sunne set, foure daies journey, is situate a Town called Sequotan,” they explained.

We can deduce that the direction, towards the sunset, was southwest by west along the north shore of Pamlico Sound. A four-day journey by canoe would have been roughly 80 miles, just as it is today. Bath Creek is almost exactly 80 miles from the north end of Roanoke Island.

For the index listing of Secotan village in the book, “A New World,” by British Curator of Drawings Kim Sloan, in parentheses is written, “near Winsteadville, NC?” Winsteadville is a small community at the head of Jordan Creek on the west bank of the Pungo River. This obscure and unexplained reference by Sloan has confused more than one archaeologist. If it took Grenville’s flotilla a full day to travel from Aquascogoc to Secotan, it is unlikely that the latter was located just 8 miles away on the Pungo River.

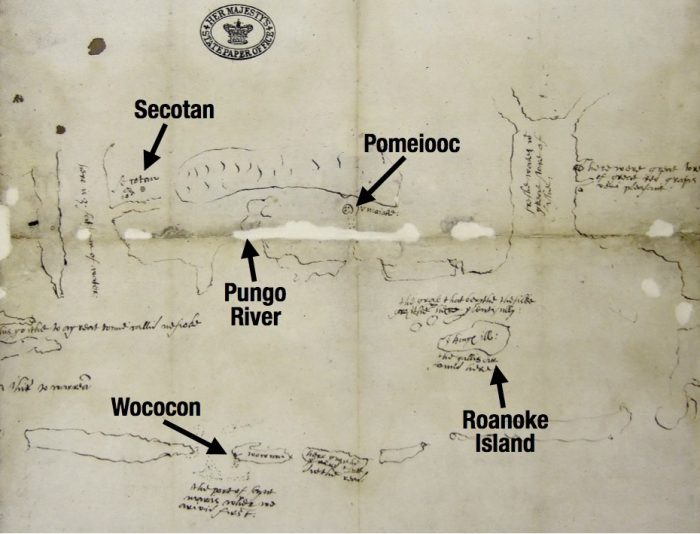

A more decisive item of evidence is found on a crudely drawn but pivotal sketch map of “Raleigh’s Virginia” believed to have been dispatched in September 1585 with four letters from Ralph Lane at Roanoke Island to Sir Francis Walsingham and his son-in-law in England. Quinn wrote: “These five items (including the sketch map) are all of the greatest interest since they represent original correspondence from the first English settlement in North America.” That ought to be a milestone in the history of the Royal Mail.

The maker of the map is unknown. The technique is not White’s, nor is the handwriting Harriot’s. Since Lane mailed it, it may have been sketched by him or one of his assistants. Quinn calls it the “earliest English map of North America made from direct observation,” and there is no doubt that it was made in the summer of 1585.

The map’s westward orientation and its geography suggests that it was copied by Theodore DeBry for his widely published 1590 engraved map, “Americae Pars.” Quinn observed that the sketch map’s value is that “it contributes several pieces of detail both to the narrative and to the nomenclature and topography of the general (‘La Virginea Pars’) map.”

Of particular interest among those items of detail is that the map locates Secotan on the north side of Pamlico River and on the west bank of a major southward flowing tributary of that river west of Pungo River. No other tributary better fits that description other than Bath Creek. “If the sketch-map of 1585 is taken as the best authority, (Secotan) was near the north bank of the Pamlico River, at, or not far, from the site of Bath,” wrote Quinn in 1955. Other authorities agree.

William Haag, an archaeologist who was contracted by the National Park Service in 1954 to complete a comprehensive cultural survey of the Outer Banks and its neighboring sounds observed that the knowledgeable Native Americans would have located their primary, summer residences on the north side of the river. “The prevailing summer breeze is from the south; thus the north shore is blown free of mosquitoes and the south shore is quieter, more humid, and insect ridden,” Haag wrote in his report.

Unlike Pomeiooc, which is marked on the sketch map as a palisaded town by a series of dots surrounded by a circle, Secotan is shown on the sketch map as an unenclosed town. White’s captivating painting of the town, a half bird’s-eye view of the streetscape, concurs. The artist must have spent quite a few hours composing the image, depicting numerous activities going on at the same time.

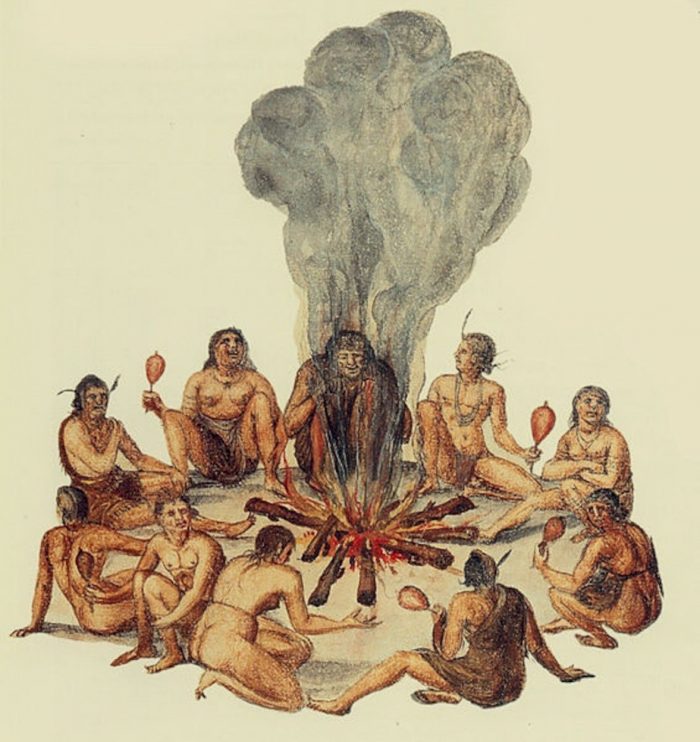

At Secotan, the Elizabethans encountered what was essentially a prototypical small American town with close knit family units, a local government, a place of worship, and a cemetery where their beloved ancestors were buried. There were picket-like fences around small garden plots, well-constructed houses with natural air conditioning, and sophisticated agricultural processes featuring rows of sweet corn, kidney beans, squash, peas, melons, pumpkins, sunflowers, and the broad leaves of young tobacco swaying in the summer breeze. The residents had festivals, cookouts, sports, dances, and occasional recitations of their history by village elders (their version of The History Channel).

Given that some measure of White’s and Harriot’s work was propaganda intended to entice future settlers to Raleigh’s Virginia, we can still accept that Secotan was a town of surprising gentility and vibrancy.

In her book, “Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America,” New York University professor Karen Kupperman wrote: “White and Harriot together argued in the most forceful and effective way that the American natives were social beings, possessing all the characteristics necessary to civility; community life and the family structure … all informed by a religious sensibility that honored the human dependence on supernatural forces in the universe.” Kupperman’s characterization is certainly reflected in White’s painting of Secotan.

Unlike the Tiger’s matter-of-fact journal entries for Monday and Tuesday of that week, the visit to Secotan must have been more memorable: “The 15. we came to Secotan and were well intertayned there of the (residents).”

The Elizabethans may have arrived just in time for the Algonquian’s midsummer corn festival. A banquet was likely served to their guests from across the sea featuring smoked fish —“the best in the world,” wrote Barlowe in 1584 — and oysters, perhaps crab, venison, rabbit, toasted hickory nuts, bread from ground sunflower seeds, and, of course, sweet corn cooked in a broth or baked as bread.

The visit to Secotan on Bath Creek also included the wondrous benefits of eastern North Carolina “uppowac” or tobacco. In his 1588 paper, “A Briefe and True Report of the new found land of Virginia,” Harriot wrote: “The uppowoc is of so precious estimation amongst them, that they thinke their gods are marvelously delighted therwith.”

Contrary to popular belief, Raleigh’s Roanoke voyages did not introduce tobacco to England, where it was already in use, but according to Quinn, it was the Algonquian’s smoking pipe that changed English habits. Numerous whole or fragments of late-woodland era smoking pipes have been found along the west bank of Bath Creek over the years.

Wine may have also been featured at the banquet, either provided by the Secotans who served it “nouveau” for lack of means to preserve it, or the Elizabethans who kept it stored in casks. Surely, the party lasted well into the night with the air filled with the smells of woodsmoke, roasting meat and sweet-smelling tobacco.

The numerous fires throughout the town kept burning 24 hours a day were, no doubt, to keep the insects at bay. The Elizabethans were well acquainted with mosquitoes, having spent time in the West Indies before arriving at Ocracoke, but on the Pamlico they might have encountered their first voracious flies. White painted one, describing it as “A dangerous byting flye.” We know what he meant.

When the festivities were over and everyone was exhausted, the English returned to their boats and anchored some distance away in the creek, again not wanting to trust their hosts entirely, who probably offered sleeping accommodations off the ground inside their well-built, bark-covered houses.

On Friday morning, Grenville’s men hoisted their anchors, raised their sails (or deployed their oars) and waved their goodbyes to their gracious hosts in order to continue their tour of the Pamlico.

There was never another meeting of the Elizabethans and the Secotans. One hundred years would pass before Europeans again ventured up the Pamlico River and by then, many of the families of the once hospitable town had long since been lost to measles, smallpox or even the common cold left behind by their English guests. The portentous sign that appeared so very terrible to the Algonquians in the spring of 1585 had come to pass.

Next: North Carolina’s least-known archaeological region