In spring 1942, the nation and its military leaders faced a dire disaster worse than Pearl Harbor.

German U-boats operating within the nation’s territorial waters were sinking Allied merchant vessels at an ever-increasing number and killing an appalling number of helpless noncombatants — more than 5,000 in fewer than six months, including some women and children. The largest concentration of losses to U-boat attacks occurred off the coast of North Carolina. Cape Hatteras was ground zero.

A late-March conference of naval officers formulating plans to implement protective convoys in U.S. waters determined that it would require 31 destroyers and 47 smaller patrol craft. On the day that their report was submitted to Adm. Ernest J. King, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Navy, there were but three destroyers on duty in the Eastern Sea Frontier and only eight other patrol craft.

Meanwhile, at any given time, there were as many as 140 unescorted ships headed northward between the Florida Keys and New York; an equal number of vessels were, at the same time, headed in the opposite direction. It has been estimated that, each day, there were 60 or more ships making their way north or south in the waters immediately off the North Carolina coast.

The protection of so many merchant ships from the onslaughts of what seemed to be phantom German U-boats was a daunting and nearly impossible task. But the inability of each ship’s cargo to reach its destination safely directly impacted the planning and preparations for an Allied invasion of Europe. A solution was imperative.

Lacking a sufficient number of warships to establish large coastal convoys in the first five months of the U-boat peril, naval authorities attempted to shuttle small groups of merchant ships up the coast during daylight in an operation called “Bucket Brigades.” Northbound ships were ordered to stop for the night at anchorages at Jacksonville, Florida, Charleston, South Carolina, the west side of Cape Fear, and the west side of Cape Lookout.

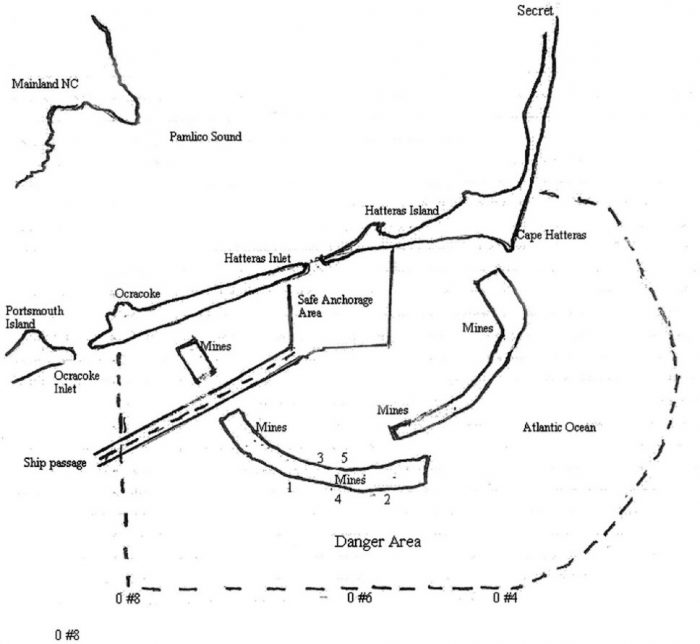

From Cape Lookout, tankers and freighters raced across the deadly 225-mile U-boat gauntlet in the Graveyard of the Atlantic before arriving at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. Slower merchant ships unable to keep up with the Bucket Brigades were to stop for the night in an artificial offshore harbor established on the southwest side of Cape Hatteras and Diamond Shoals, encircled by a mined anchorage much like the British minefield guarding the Thames estuary.

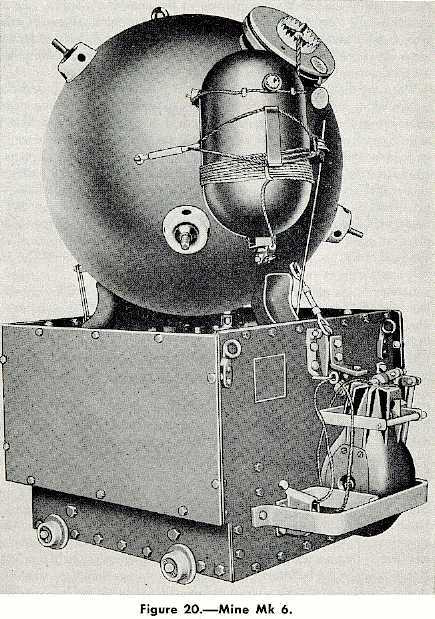

In the month of May 1942, 2,635 Mark-6 Naval Contact Mines were anchored in place along a 35-mile-long semicircle extending from Diamond Shoals to a point off the beach about 4 miles east of Ocracoke village. Each mine was chained to ride a few feet below the ocean surface. The Mark-6 contained an explosive charge of 300 pounds of TNT that would be triggered by a contact pistol when the mine was bumped by a vessel. The problem was that a mine did not know the difference between an enemy U-boat or an Allied vessel.

On the western perimeter of the minefield, a few miles southeast of Ocracoke village, an opening wide enough for tankers to pass in and out of the protected anchorage led to a designated 36-square-mile box directly south and east of Hatteras Inlet where the ships were to drop anchor for the night.

When an inbound ship approached, a U.S. Coast Guard pilot boat guided the ship through the minefield opening and to the anchorage off Hatteras Inlet. At dawn on the following day, the routine would be repeated in reverse. On paper, the operation seemed simple enough, but plans on paper often don’t take into account the vagaries of weather.

Seventeen days after the Cape Hatteras protected anchorage opened for business, the Standard Oil tanker F.W. Abrams lost contact with its pilot boat while departing in poor visibility and struck a mine. The ship’s captain thought that they had been torpedoed. The anchor was lowered but the ship began to drift in the heavy rain and fog. In less than an hour, two more explosions rocked the ship, finally sinking it.

The captain and crew abandoned the tanker and made it safely to shore at Ocracoke Island. They were certain that they had been relentlessly attacked by a German U-boat. Instead, they had run into three, American-made, Mark-6 contact mines. The Cape Hatteras minefield had claimed its first victim. Two months later, the minefield sank two more Allied vessels and damaged another. The Navy’s minefield was doing the German’s work for them.

During World War I and after, Great Britain devised, tested and installed numerous technologies for anti-submarine detection at many of its strategic ports, harbors and outlying anchorages. One of the more intriguing and highly secret British technologies proved its effectiveness in 1918 — an underwater magnetic indicator loop.

Even when a U-boat’s magnetic field was degaussed, the steel hull continued to emit a small electric current that could be detected by electromagnetic induction via an underwater stationary loop of cable connected to sensing equipment on shore. By such a method in 1918 the British Navy detected the incursion of a German U-boat, UB-116, into the mined anchorage of the naval base at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

In support of the Cape Hatteras minefield, the U.S. Navy established in the summer of 1942 a magnetic indicator loop station on Ocracoke Island. The Navy chose a site atop an ancient sand ridge, about halfway between the village and the beach.

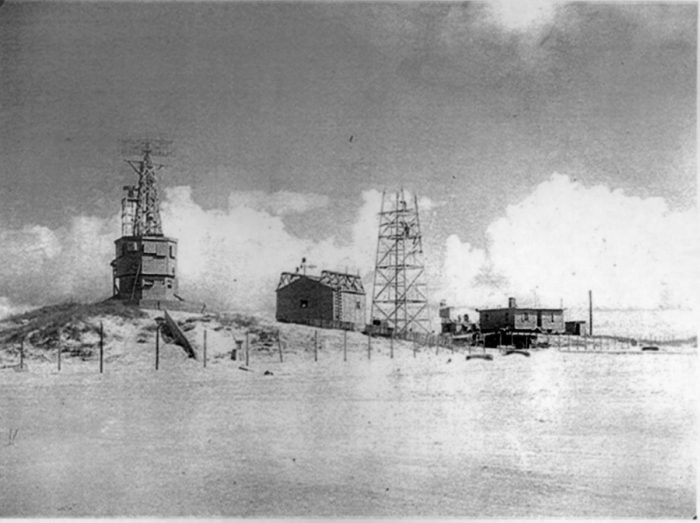

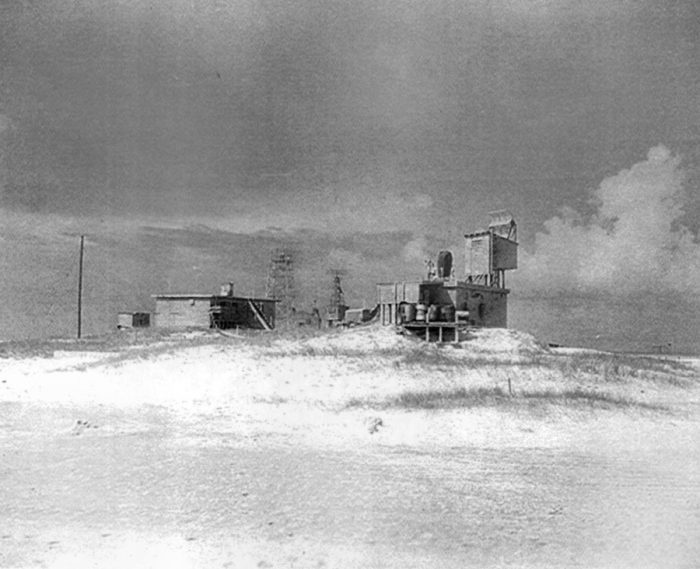

The ridge, 30 feet above sea level in places, overlooked a vast and barren tidal flat that separated the island’s beach and the village, but which has long since been covered by dunes and vegetation. The sand ridge provided a relatively high vantage point for the buildings and towers that would be built there; the setting also made the secret station plainly visible to the nearby island residents who were prohibited from venturing beyond the limits of the village during most of the war.

The well-guarded complex at Ocracoke was surrounded by a barbed wire fence and comprised an area of about 11 acres. As many as eight structures linked by wooden walkways and sandy paths were eventually built at the site, including odd-looking towers and peculiar rotating antennas. The Navy referred to the installation as a “loop receiving station.” Ocracokers called it “Loop Shack Hill.”

“They wouldn’t let nobody but a special certain people go into the enclosure out there,” former World War II Coastguardsman Ulysses “Mac” Womac told me in an interview in 2000. Womac was assigned to overnight beach patrols and often passed the station. “They had guards out to where nobody could get up to where they was at. They stood watch out there on the hill. In fact, they lived out there, a few of them did. And they stood watches and listened on earphones for what was offshore. Now, where they had the cable offshore I don’t know. But we saw it on the beach, or I did before they buried it.”

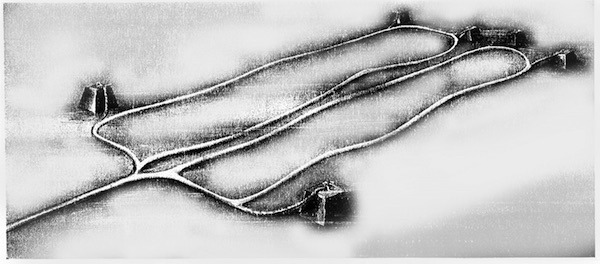

In late May and early June 1942, a Navy net tender from Norfolk laid at least two indicator loop arrays on the ocean bottom beneath the approaches to the entrance of the mined anchorage. The loop arrays were anchored to the bottom at a sufficient distance from the minefield to allow advance warning that a submerged U-boat was approaching the area. Each array consisted of a 1.3-inch-diameter, lead-sheathed, single-core cable that was configured in two rectangular-shaped loops.

At other U.S. Navy indicator loop installations, the average length of a single loop field was 2 to 3 miles; the longest could be up to 6 miles long . The cables forming the two loops were spliced to a tail cable, which connected the array to the receiving station on shore. Tail cables could be many miles long depending on the distance from the receiving station to the location of the indicator loops offshore.

When a vessel, either on the surface or submerged, crossed over the indicator loop array, an induced voltage was produced that was detected on an instrument called a fluxmeter at the receiving station, and the result was recorded on a paper chart. The watchstanders on duty would interpret the electronic signatures on the chart and then use a telescope to determine if a surface vessel was crossing the loop field. If no surface vessel could be seen, it would be assumed that a submarine was approaching, and appropriate action would be taken by patrolling vessels.

At Ocracoke’s loop receiving station, a concrete casemate housed the operations building that contained all the facility’s detection equipment including fluxmeters, chart recorders, communications gear, telescopes and furniture for four men. The Ocracoke station also was equipped with an early version of a microwave surface-search radar system, which was erected on top of the operations building.

Other cutting-edge detection technology included radio sonobuoys and high-frequency radio direction finding, also known as HF/DF or “Huff-Duff.” In addition to the “Huff-Duff” hut at Ocracoke’s loop receiving station, similar HF/DF receiving stations were located at Coast Guard Lifeboat Stations at Cape Lookout and Poyners Hill, which was south of the Currituck Beach Lighthouse.

When the Navy finally got done building, equipping and manning Ocracoke’s top-secret loop receiving station, it was one of the more complex, state-of-the-art defensive installations on the East Coast. But by the time the installation was operational, there were few, if any, U-boats operating off North Carolina’s coast for the station to detect.

The tide turned in the war zone in the western Atlantic when the first, fully escorted coastal convoys began transiting the middle-Atlantic states in mid-May. By then, the skies were patrolled by military and Civil Air Patrol aircraft. Small patrol vessels armed with two-way radios crisscrossed the sea lanes. Shorter periods of darkness also limited the time that German U-boat could safely recharge their batteries on the surface.

Between April and July, four U-boats were sunk by Navy and Coast Guard warships and an Army A-29 bomber off the Outer Banks. Germany began redeploying its U-boats to the North Atlantic and Mediterranean theaters in mid-July 1942. For the remainder of the year, 160 coastal convoys were conducted between Galveston and New York. During that time, only three Allied merchant vessels were sunk, and one was damaged by U-boats while the ships were shepherded in convoy.

Ocracoke’s Loop Shack made no contribution whatsoever to the effort to defeat German U-boats in the war zone off North Carolina’s coast. Not once at Loop Shack Hill did the fluxmeter’s paper plotter record the signature of an enemy U-boat, nor did the Navy’s surface search radar system register a U-boat’s blip. It succeeded, however, as a valuable experiment and training facility — the lessons learned were later applied to detection of Soviet submarines during the Cold War years.

A year after it was established, the Cape Hatteras minefield was swept by the Navy to remove the Mark-6 mines. Fewer than half of the mines moored in 1942 were recovered. Overall, it has been estimated that the U.S. Navy placed 20,000 mines in United States waters for defensive purposes during the war. Not a single German U-boat or Axis vessel was ever sunk by the mines, but three Allied vessels were destroyed by the Cape Hatteras minefield. And even to this day, a few of the rusty, barnacle encrusted contact mines wash up on a North Carolina beach.