(This article is republished from an August, 1999, special section of The Island Breeze on the move of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.)

They are engineers and laborers, historic preservationists and stone masons, designers, inventors, and jacks of all trades.

They are northerners, southerners, and Hatteras Islanders.

They are the men who have moved the Hatteras Island Lighthouse.

They worked long hours, at times two shifts a day six days a week to get the lighthouse ready for its historic trip down a special roadbed to a new home some 2,900 feet — a bit more than half a mile — from where it was built 129 years ago.

The National Park Service first recommended moving the lighthouse to preserve it from the encroaching Atlantic Ocean in 1989. While the move didn’t grab the attention of Hatteras islanders, many of whom eventually opposed it, until a few years ago, moving men across the country have been thinking about it, planning how it might happen, and having dress rehearsals for more than a decade.

THE GENERAL CONTRACTOR

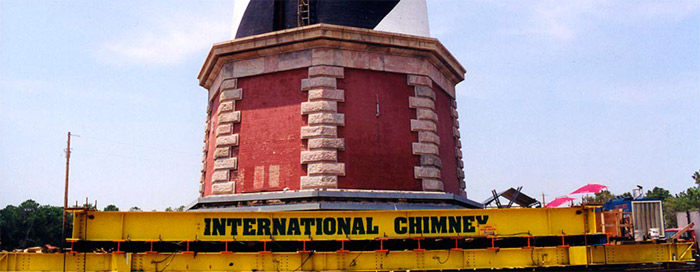

Foremost among those that were preoccupied with moving the lighthouse was International Chimney Corp. (ICC) of Buffalo, N.Y., the company that was chosen by the National Park Service as the general contractor on the $12 million project.

International Chimney is a 70-year-old company that started out building and repairing tall masonry structures, such as church steeples and chimneys. Most of the work was institutional and industrial — chimneys for steel and power plants. As the landscape of the industrial world changed and the demand for chimney construction plummeted, the company branched out into historic preservation — renovating and relocating big structures.

The company has been involved in historic preservation for about 20 years and the percentage of preservation work varies — never more than half and usually less, according to ICC president Rick Lohr.

International Chimney has been the general contractor on moves of historic theaters in Detroit and Minneapolis and will be moving an arch in Ohio. Lohr describes them as “emotional” moves.

“The arch in Ohio has no practical use. It’s being preserved just for the art and beauty,” he says.

“People are possessive about their history,” he adds. “And Cape Hatteras goes beyond that because of the intense national interest in the lighthouse.”

Lohr says ICC pursued the lighthouse relocation “with enthusiasm and great effort.”

“A couple of the jobs that led up to the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse turned out not to be profitable, but we would have bid on them anyway because they gave us experience we would use on this project.”

One of those jobs was moving a tall brick chimney for Corning Glass in Pennsylvania, an experience that gave the company information that it used to relocate the world’s tallest brick lighthouse, which has been described by one subcontractor as “just a chimney with a light on the top.”

THE PROJECT MANAGER

International Chimney’s project manager for the move is Joe Jakubik, who heads the company’s historic preservation division. He’s a lighthouse “specialist” and has managed the company’s renovations of such lighthouses as Cape May in New Jersey, Montauk Point on Long Island, Brandywine in Delaware Bay, Tybee Island in Georgia, and Falkner’s Island in Connecticut. He’s also presided over ICC’s three previous lighthouse moves — the Southeast Lighthouse on Block Island and the Highland and Nauset lighthouses on Cape Cod.

Jakubik first saw the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in 1989, when International Chimney was preparing to bid on structural renovations. The company won that contract and completed the renovations in 1992, and Jakubik readily admits that he’s been thinking about the move ever since.

“I’ve been thinking about it for years,” he says. “The where, the when, the steps in doing it, what I was going to have to deal with.”

Both Lohr and Jakubik are careful to note that each lighthouse move has presented its special challenges and each has had its historical and emotional significance to the people of the region. But Jakubik adds that he has viewed the others as “gearing up for Hatteras.” Block Island in 1993, he says, was a “dress rehearsal.”

The reason, Jakubik says, is that the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is the “granddaddy of them all.”

“There are others that are similar — St. Augustine, Bodie Island, Currituck. But this was the first, the most ornate. It has the most detail that has survived. Cape Hatteras has remained basically unchanged. It’s a very impressive engineering feat for the time, very well constructed.”

Each lighthouse move has been a challenge for the movers. The other three, for example, have keeper’s quarters that are attached, making the load that was moved much more uneven. But Cape Hatteras, Jakubik says, is the most expensive and intensive of the moves.

Normally the company would use the same crew and would move from one task to the next. At Hatteras, more men have been involved and multiple activities were happening at once. In the spring, the lighthouse foundation was being removed, keeper’s quarters were being relocated, roadbeds were being prepared, and the new foundation was laid.

Every two weeks from January into August, the National Park Service had a media conference at which various officials briefed reporters and camera crews on the progress of the move.

Jakubik is serious and intense, but when it came to answering questions, he was known among reporters as someone who liked to talk about the move — sometimes at great length and in great detail.

THE SUPERINTENDENT

International Chimney’s site superintendent, on the other hand, is just the opposite.

Skellie Hunt is outgoing and garrulous, joking with reporters and answering their questions in clipped sentences. He would often grab a notebook out of a reporter’s hand and start drawing pictures to explain a particular detail of the move. Early on, he herded the media around the site and was driven to distraction by photographers and cameramen who tended to wander around rather than “stay together,” as he so often admonished them.

A North Carolina native who graduated from North Carolina State with a mathematics major, Hunt was a builder and developer in Wilmington until about three years ago when he came to the attention of International Chimney, which bid on replacing a church steeple damaged by a hurricane. International Chimney didn’t get that job, but Hunt went to work for them, doing other sales-oriented work.

“I think this (Cape Hatteras) was in the back of their minds back then,” Hunt noted during an interview at his makeshift desk in the tiny, cluttered, and very busy International Chimney trailer on the lighthouse site.

Indeed, Joe Jakubik says that Hunt was chosen for the job for, among other things, his North Carolina background and his experience working with subcontractors.

Joe Jakubik invited Skellie Hunt to Hatteras, and on a cold November night last year, Hunt got his first look at the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. He looked over the job and pronounced it “awesome.”

“I’d heard about it, but to stand at the foot of it and look up and think, ‘Are we really going to do this?'”

On the site, Hunt is charged with coordinating the many different subcontractors and making sure the move stays on the schedule, materials arrive on time, and many other details.

International Chimney officials don’t refer to the other companies involved as “subcontractors.” They are careful to stress that all are a team, and business cards that are handed out list the “International Chimney Corporation Team.” They include Expert House Movers of Maryland, and various engineering companies. Many are based in North Carolina or have offices in the state and Steve Crum’s Buxton construction company is called in, according to Hunt, “whenever we need a hole dug.”

The chief engineers on the move have been George Gardner of International Chimney, Dave Fischetti of D.C.F. Engineering of Cary, N.C., and Pete Friesen, a 77-year-old internationally known move designer.

THE CREW

International Chimney has had about 10 to 30 men working at the site, depending on the task at hand. Only four have come from Buffalo, and the rest have been hired from elsewhere, including Hatteras Island.

Heading up the on-site efforts for International Chimney during the removal of the foundation was Mike Vacanti, general foreman, and John Mitchell, dayshift foreman. They have supervised the preparatory work, including the arduous removal of the lighthouse’s granite-and-mortar foundation and its replacement with shoring towers. Once the foundation was removed in early May, Vacanti and Mitchell headed back to Buffalo.

Other International Chimney employees moved on to other work at the site after the foundation was removed. They have come to the move from any number of states, including Virginia, Georgia, and Florida and from Hatteras Island.

Richie Meekins of Avon was among the first hired by ICC. He’s a building contractor who ran the Avon Motel for seven years. He called up early on to inquire about a job with the moving team and was instantly hired on as a foreman. He’s worked on moving the keeper’s and doublekeepers’ quarters and on the footings for the new foundation. He’s been an all-around problem solver and his work gets high praise from all of those he has worked with. Meekins has brought other Kinnakeeters to work at the site.

Among them is Jamie Markley, a local musician who went to work as a laborer. “I was originally against the move like anyone who lives down here,” he says. “But I love the lighthouse and wanted to be part of this. It’s a part of history, an engineering feat. It’s amazing.”

Most of the other workers echo Markley’s reasons for wanting the work.

Alan Scarborough, also from Avon, wanted to work on the move because “it’s only going to happen once in my lifetime.”

Robert Penfield of Buxton, an electrician by trade who has worked a variety of jobs on the island, also signed up as a laborer and has been a jack of all trades at the site.

“It’s an interesting job,” he says. “It ain’t going to be done but once.”

ICC’s Vacanti feels about the same way as most of his workers.

“It’s a piece of history,” he says. “These people down here and the way they feel about it (the lighthouse) is really something.”

Vacanti and Mitchell lived in Avon until they returned to Buffalo and they both were full of praise for Hatteras islanders in general and Kinnakeeters in particular.

“Kinnakeeters are definitely the best people on the island,” Mitchell says. “They invite you to their houses and bring food to your house.

“I can’t say enough about the people. The people in the area have gone out of their way to make us feel comfortable.”

Even though many islanders opposed the move and favored other means to save the lighthouse, the men working at the site agreed that they had heard little from the locals.

“A few people had something to say,” Robert Penfield notes.

“I expected human chains and picket lines,” says Skellie Hunt, “but everyone has been superb.”

Joe Jakubik agrees that the Hatteras relocation project is the most controversial the company has been involved with, and it has also attracted the most attention from the public and the media. He says he doesn’t mind either, just considers it part of the job.

Jakubik’s attention to detail on the job extends to the people who want to see the historic move. He says that’s because International Chimney is working for the National Park Service and the National Park Service is working for the public. In part, it’s because people who work for him describe him as “a really thoughtful” man who “wants everybody to be happy.”

Jakubik fretted last month that a load of steel beams ended up next to the orange fence around the construction site right in front of the walkway where tourists gathered to watch the foundation removal.

“I hadn’t intended for that to happen,” he says. “I try to put myself on the other side of that fence.”

A public viewing path was extended along the fence as the lighthouse made its trip to the southwest.

One day in early May, the lighthouse foundation was down to a mere pillar of granite and mortar and its load had been shifted to the orange shoring towers.

Skellie Hunt led the media on one last tour underneath the light before shoring towers completely filled the area that had once been its foundation.

When Jakubik first explained to him how the foundation would be removed, Hunt was astounded. “You’re going to stand under there?” he asked his boss. The amazement was still in his voice as he recounted the story.

Now Jakubik and Hunt and scores of workmen and visitors have stood underneath that foundation. Their trips underneath the light have been reported by dozens of reporters, photographers, and cameramen.

And Skellie Hunt is still amazed. He’s not a man really impressed by the historic significance of the lighthouse move.

“What’s important to me are the engineers,” he says.

“It’s a mixture of science and art,” says ICC president Rick Lohr. “There are sound engineering principles involved…and the art I’m speaking of is the feel for it, the feel for smokestacks or lighthouses.”

Although reporters joked with Hunt about whether he had a getaway plan in case the move went awry, you didn’t have to ask the moving men the most obvious question about the move. You just knew that all of them believed that it could be done and that they would do it.