On August 16, 1918, Surfman Number Eight of the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station, Leroy Stockton Midgett, took the watch in the tower of the still-new 1911 station. Although this was three years after the Life-Saving Service had been recreated as the Coast Guard, these folks had been used to the old terminology for many years and consequently continued to use them for some time. On that beautiful August day, there was extremely heavy surf lingering from a storm the day before. Leroy was nervous about his responsibility that day for two reasons – the surf was enough to cause shipwrecks. But more than that, Leroy knew something that nobody else in America knew, except the military. As part of that military, the Coast Guard especially was informed.

When World War I came to our shores in 1917, America was totally and completely unprepared. We had zero defenses for the ultimate stealth weapon of its day, the German submarine.

What Leroy did know was that the day before, German submarine U-117 was seen on the surface of Chesapeake Bay, just miles north of Chicamacomico. She had been laying mines in the waters around one of America’s largest Navy bases. Worse yet, U-117 was seen exiting the Chesapeake heading south – in the direction of Chicamacomico. The best guesses at what would occur next was that U-117 would probably head for the Wimble Shoals to lay more mines. These massively large shoals created a very narrow shipping channel – which makes a perfect target! These shoals were directly offshore from the Chicamacomico Station.

At 4:00 p.m., looking out one of the south tower windows, Leroy witnessed what he had been dreading all day: he spotted a large ship on August 16, 1918, the British tanker SS Mirlo. He watched it slowly creep north, heading towards his station. By 4:30, the Mirlo was seven miles offshore, almost directly opposite the Chicamacomico Station. To his horror, Leroy saw a huge plume of water rise hundreds of feet into the air from the aft of the tanker, followed by an explosion so loud it shook the ground of his building and rattled its windows from seven miles away.

“Captain Johnny, a ship is in trouble!” he hollered out of one of the open station tower windows. He was referring to John Allen Midgett Junior, the Keeper, (now a Chief Bosun’s Mate) or Officer in Charge, of the station. Almost always, there were eight surfman and the Keeper at the station. Of all days, on August 16, there were only five surfman and Capt. Johnny, because two were sick and one was on leave. Immediately, these six hurried to the boathouse where Surfboat Number 1046 was kept. They rolled her out on its four-wheeled cart and attempted an immediate launch. But the surf was so heavy that it tossed that multi-thousand-pound boat back upon the beach.

The Mirlo was carrying a full cargo load of 6,679 tons of gasoline, high-octane aviation fuel, and other petroleum products when that explosion happened. The Commanding Officer of the Mirlo, Captain Williams, quickly ordered his ship west, trying to beach her, but he only got two miles when there was a second explosion. Captain Williams knew he was in deep trouble, so he ordered his men to abandon ship. Here is where the real quandary began: The Mirlo carried two lifeboats with a capacity of eighteen each, and she had a crew of 51. The first lifeboat – filled to capacity – got away safely, and the crew began rowing for their lives at breakneck speed. The second lifeboat – also filled to capacity – attempted to launch, but as it was being lowered, got fouled in the rigging, capsized and dumped all its occupants into the turbulent sea below. Yet that was not their main problem; they were five miles offshore and probably didn’t have a ghost of a chance of making landfall. Most importantly, the biggest problem developed when a third explosion erupted. This earth-shaking explosion ripped the Mirlo in two, releasing her entire explosive cargo of over six and a half thousand TONS of gasoline, which, as we all know, floats on top of water – and will burn, on top of water – and it ignited. The resulting inferno was too large to describe or even to imagine. One local newspaper’s headline at the time simply read “Ocean Catches On Fire.” By now it was 5:00 p.m. With all that noise, fire, and smoke, most of the men from the village of Rodanthe and even lifesavers from the Gull Shoal Station to the south showed up. Even with that help, it took a full 30 minutes to finally launch through the raging surf.

After Surfboat No.1046 got past the violent breakers, Capt. Johnny could only see two things: a small lifeboat in the distance full of survivors, and a wall of flames. Upon reaching the lifeboat, Capt. Johnny encountered some of the British sailors of the Mirlo. He learned that the rest of the crew were trapped in that inferno. Capt. Johnny warned the sailors to row close to shore, but not to attempt to land. “We are trained professionals and we had a very difficult time getting though the treacherous surf. What a shame if you survived this calamity but then drowned getting ashore. Wait for us; we will help.”

Quickly then, Capt. Johnny and his crew of five went out five miles and encountered a wall of flames, literally hundreds of feet tall.

Here is what happened next: As Capt. Johnny’s crew circled this huge wall of flames, suddenly, as if in a Hollywood movie, there was a break in the smoke and flames. Through this opening the surfmen could see an overturned lifeboat. Without hesitation, Capt. Johnny turned Surfboat No. 1046 through the opening. Even though it was an opening, the heat was so intense that it singed their facial hairs, smoked their cork life vests, and blistered the paint on the boat.

As the lifesavers approached the capsized lifeboat, this is what they found: six men, coming out from underneath the capsized lifeboat, scraping the flames aside, and gasping for a second or two of air. Their worst nightmare ended as they were pulled safely into Surfboat No. 1046… or had it? Something was wrong. They should have been getting out of there with all great haste; instead, they remained in that treacherous area. The reason? Capt. Johnny knew full-well that the British lifeboat would not have been launched with just six men, it would have had a full contingent of crewmen. He is looking for the other sailors. The survivors told Capt. Johnny that they saw their shipmates go down and that they never came back up and urged him to get out of there. Even with that information, Capt. Johnny and his crew continued to look for survivors – in an inferno – because that is what they do.

Finally realizing there were no more survivors there, Capt. Johnny and his crew went back through the wall of flames and finally headed for shore. The British sailors must have explained that when their ship was split in two, they saw nineteen of their shipmates on the stern. It was engulfed in flames and was going down like a rock. If there was a sliver of a ray of hope, this is it: The stern is where the captain’s launch is kept. It is not a lifeboat, it is just a small vessel for the captain and a few crewmen to go to shore, but at least it is something.

Indeed, it was. These were desperate men in a highly desperate situation, and it was all they had. They launched it. As soon as it hit the water, they discovered that they were in even more trouble. The small boat was far too overloaded, the water reaching to the gunnels and about to sink the small craft. Even worse than that, it was so crowded that there was no room to row, putting them at the mercy of the south wind, which carried deadly flames. Hearing this, Capt. Johnny, already five miles offshore, took his crew of five, the six English sailors, and Surfboat No. 1046 a mile farther south searching for more survivors. They went three miles. Then six. Nine miles later, they came upon a small boat with nineteen men aboard. Covered in oil, blistered and battered, but alive. Capt. Johnny took that boat in tow, struggled the nine miles back, against the wind, met the other lifeboat they had instructed to wait, and began to ferry the survivors ashore one boatload at a time. It took four trips. By 9:00 p.m. that night, 42 English sailors stood on the sands of Hatteras, headed for Chicamacomico, alive due to the impossible heroics of the men of Chicamacomico.

After enduring a 6.5-hour hellish ordeal and traveling a total of 28 nautical miles in Surfboat No. 1046, the gallant crew of Chicamacomico had been successful. In his wreck report, Captain Johnny concluded, in typical lifesaver understatement “Returned to Station 11:00PM. Myself and crew (sic) very tired.”

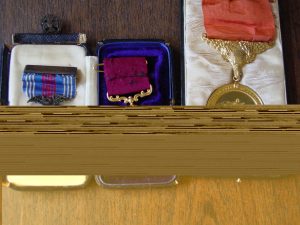

The Grand Cross of the American Cross of Honor

In the early 1900s, Congress created the supreme medal for valor. It was to be the ultimate recognition for outstanding bravery. It was called The Grand Cross of the American Cross of Honor. It didn’t matter whether the person was military or civilian, man or woman, black, white, or whatever. It had to be “extreme valor to the utmost degree.” Consequently, the requirements were so lofty and stringent that rarely did anyone ever qualify for it; so, sadly, eventually it was dropped. In its 30-year reign, nationwide, only eleven were ever issued. Six of those recipients rowed together on August the 16th, 1918 in Chicamacomico’s Surfboat No. 1046. That made it the most-highly awarded maritime rescue in U.S. history. That very boat is on display in Chicamacomico’s 1874 Life-Saving Station. It is a testament to the Mighty Midgetts of Chicamacomico, whose sheer will, dedication, determination and commitment rose above all others in the annals of life saving history. They would not be deterred, because that is just what they were born to do. That’s why at Chicamacomico, we said “the Midgetts are big around here!”

These are only excerpts from Chapter 3 of my book, Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks: Dramatic Rescues and Fantastic Wrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic, Globe Pequot Press. The complete chapter contains much greater detail. This is one of the stories that I will be presenting at the Bald Head Island National Lighthouse Day Event on August 5. I will also be signing books at the “Nora’s Wish Chicamacomico Treasures & Nostalgia” Shop on August 16. The quaint and gem of a shop is located in Rodanthe on Highway 12 just opposite of the North Beach Campground and Convenience Store.