Gathering the oddly shaped shellfish Crassostrea virginica, better known as the common oyster, has long been an important part of Ocracoke Island’s fishing tradition, and freshly gathered oysters one of her finest culinary delights.

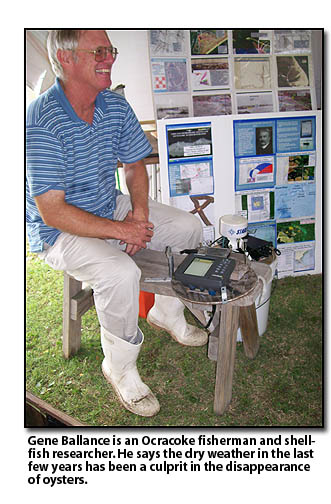

Ocracoke fisherman and shellfish researcher Gene Ballance explains that for his grandfather, Elisha Ballance Sr., oystering was the main source of income in the winter. He and other Ocracoke fishermen sailed their skiffs into Pamlico Sound and gathered the oysters using hand-held tongs. They sold them to what were called “buy boats,” which took the shellfish to New Bern, N.C., or sent them to such places as Washington, N.C., on freight boats.

Big Al Styron, the owner of the grocery called Styron’s store, lost his life one winter day while oystering in Pamlico Sound. His boat was recovered but his body was never found.

Ocracoke fishermen and residents look forward to winter days when they can feast on the odd little shellfish, eating them raw, roasted, steamed, or fried.

This past December, however, at the Ocracoke Working Watermen’s Association’s (OWWA) annual oyster roast, all the oysters had to be bought from Swan Quarter. Ocracoke’s oysters were too scarce to harvest.

Oyster communities, or reefs, as they are called, are important for many reasons other than their culinary desirability. They create important habitat where many other aquatic species live and feed, and they filter and cleanse the water as they feed on plankton.

As Ocracokers realized over the past fall that most of the offshore oyster reefs were dead, they wondered what had killed them. The first thought that came to many people’s minds was “pollution.” Everyone has heard stories about shellfish bed closures along the North Carolina mainland due to run-off from agri-businesses and sewage plants, and oystering is no longer allowed in Silver Lake or along certain other shores of the island because of local pollutants.

According to Gene Ballance, however, most of Ocracoke’s waters are still clean and safe for oysters. The culprit, according to Ballance, was the dry weather that plagued the state during the last several years.

In dry years when there is less rainfall to dilute the salt in the waters of Pamlico Sound, salinity increases. Ocracoke, being close to Atlantic Ocean inlets, typically has a higher salinity than mainland areas, such as Swan Quarter, which receive more freshwater from rivers. Oysters require a certain level of salinity to thrive–somewhere between 12 and 18 parts per thousand, which in normal years Ocracoke has.

Some of the water around Ocracoke tested as high as 30 parts last year, however, and the oysters could not survive. Oysters in waters nearer the mainland thrived as the salinity there reached ideal conditions, which is why the Ocracoke Watermen’s Association was able to obtain a healthy crop from Swan Quarter.

Why is the salinity level so important for the oysters’ well-being?

One of the reasons, explained Ballance, is because one of the oyster’s main predators, the boring sponge, thrives in salty water. The sponge secretes an acid which bores holes in the oysters’ shells, causing them to be brittle and vulnerable to other predators, such as crabs.

Blue crabs and sometimes tiny mud crabs have always preyed on Ocracoke’s oysters, but now there is a new danger. Stone crabs, once rare in these waters, have been migrating north, possibly because of climate change and global warming. They have become an increasing threat to oyster beds, and in a year when high salt levels encouraged boring sponge predation and extra vulnerability, they may have been the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back.

Disturbing as this situation is, it is far from hopeless. Ocracoke’s oyster beds have existed for hundreds of years, and they have seen natural and human-induced declines before. There is a plan in place for replanting them, and the Ocracoke Foundation’s oyster restoration project is already underway.

A shallow draft barge was purchased with funding from the Golden LEAF Foundation, which received money from the tobacco settlement to help communities create and maintain jobs. The barge, named the Francis Winslow II, will be used to replant Ocracoke’s shallow reef oyster beds, identified on a map created by U. S. Naval officer Francis Winslow II in 1888. The map identifies about 6,000 features that will help scientists determine where to plant the oysters.

“Planting oysters” really means setting out cultch material (a substrate of seasoned oyster shells or sometimes scallop or broken clam shells) for swimming oyster larvae to attach to. Seasoned shells are those that have been dried out for six months to a year, so that parasites and predators such as oyster drills are no longer attached to them, and they form a slick surface.

Timing for planting the oysters is critical. Oysters spawn in summer, producing larvae that swim around until they find a place to attach. Once attached, the young oysters, known as spats, never move again.

The larvae compete with barnacles and other organisms for appropriate substrate, so it is important to set out the cultch when the oyster larvae start moving around and can get there first. That happens when the water temperature is around 68 degrees, typically in June or when crabbing season ends.

This should be a good year to plant the oysters, Balance says, since El Nino weather patterns call for a wet season, with better salinity levels.

The North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries already has five major oyster spawning sanctuaries in Pamlico Sound. One is two miles north of the sunken dredge Lehigh near Ocracoke.

Additional monies for funding the oyster restoration project come from the newly created American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRK), which is better known as the stimulus plan.

Marine Fisheries recently sent out an announcement the agency will be hiring fishermen to plant oyster shells in four coastal counties this spring, including Hyde County, of which Ocracoke is part.

Fishermen who are interested in participating can call Clay Caroon, the head of the cultch planting program, at 252-808-8058.

Gene Ballance and other Ocracoke watermen are optimistic that the oyster restoration project will be a success, and that Ocracoke’s shallow-water oyster reefs will be providing habitat, clean water, and good eating in a few years.