A project the size of the “jug-handle” bridge north of Rodanthe is like some intricate dance routine carried out with mammoth custom-built gantry cranes, massive 155-foot pilings and teams of workers each with their own tasks.

“The whole system is one big train. You only move as fast as your slowest part of the train,” said Adrian Price, project manager with Flatiron Construction Corp., the Broomfield, Colorado-based contractor for the project.

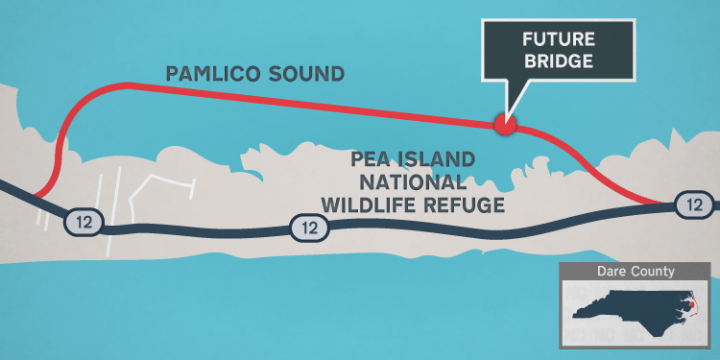

The process of building a bridge 2.4 miles in length is familiar to those who witnessed construction of the Marc Basnight Bridge, which was completed last year, and it’s complex. Pilings are driven deep into the bed of Pamlico Sound and capped, girders laid, then subsurface and surface layers go into place, all while heeding the natural surroundings.

Construction began in 2018. Bypassing the frequently storm-washed S-curves of N.C. 12 north of Rodanthe and jutting out over Pamlico Sound, the jug-handle bridge, so named because of its distinctive shape that was designed to minimize adverse effects on the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, is in numerous ways different than most bridge projects.

“Typically, a bridge like this, you build it with a temporary road on the side or you build it with barges,” Price said. “But with the shallow water here and the limited right of way, we had to come up with something different.”

What Flatiron has come up with is a temporary rail system on the outside of the bridge. Moving along the rails are two huge gantry cranes that are used to maneuver the pilings and other heavy items into place.

“The two big yellow gantries that you see, the gantry cranes, we purchased from a company in Italy,” Price said, adding that the cranes were a custom design built for the project.

As each section is completed, the rail system is disassembled and removed to the far end of the project.

“A rail cart then delivers it to the front of the rail to the lead crane, so that we’re able to leapfrog the whole system forward,” he said. “The train only works as fast as the slowest piece.”

That’s something that Ricky Hires knows well. Hires runs the pile driver at the front end of the project. The piles support the gantry rail system.

“We make the bridge work,” he said. “I think it’s one of the best systems I’ve ever seen, and I’ve done this for a long time, about 32 years.”

Hires noted how important it is that his team stays in front of the rest of the project.

“We’ve got a crew of four, counting myself … everybody knows his job. (If) anybody falls behind, we all fall together,” he said.

Maneuvering a piling into position is a carefully choreographed, half-hour dance that begins with the piling being lifted from a truck and fitted into a cradle that supports it and keeps it from swinging too much in the wind. Then giant rings clamp onto the piling and lower it into place. Next, a massive plywood ring is fitted over the top. That is what the hammer of the pile driver strikes, not the pile itself.

At times, there are two pile drivers simultaneously pounding pilings into the bed of Pamlico Sound as Hires and his team extend the railings forward with one as the larger crane drives a bridge piling.

Price said that the jug-handle bridge is also unlike other projects that he’s supervised because of the environmentally sensitive areas that surround it. But Pablo Hernandez, the North Carolina Department of Transportation’s resident engineer here, said that what the Flatiron project manager sees as unique is the norm for highway construction on the Outer Banks.

“We’re used to the entire project being in an environmentally challenging area. Whereas somebody who hasn’t worked here on the Outer Banks before, or in eastern North Carolina, has come from a more inland area (where) the project may be several miles long but only have just a few isolated environmentally sensitive areas,” he said. “It’s pretty well known those are the no-go zones. But here, it’s a completely different scale and can be easy to forget that you’re always in an environmentally sensitive area.”

Also for Hernandez, who has worked out of the Manteo office for years and was the resident engineer for the Capt. Richard Etheridge Bridge over New Inlet, which was dedicated in February 2018, and the Marc Basnight Bridge, which was dedicated last April, there is something different about this project. The jug-handle bridge involves work on private property and cooperation with private property owners.

He had to think for a moment about when he last worked on a major project that involved private property.

“Not since probably 2010,” he finally said.

If all goes as planned, the bridge will probably be open by late summer 2021. There’s a lot of factors that could delay completion, mostly weather related, and there has already been at least one hiccup along the way.

Back in December, inspectors noticed cracks in some of the pilings being fabricated in Chesapeake, Virginia. The size of the cracks didn’t matter; any crack is a disaster waiting to happen.

Creating a hollow tube of concrete 150 feet or more in length is complex process.

“Just to say you’re going to make something hollow sounds simple, but then when you start thinking about it, how do you make it be hollow? Then how do you pull that piece?” Hernandez asked.

What NCDOT and FlatIron Construction discovered was the removable form inside the piling had been moving during casting.

“We found that that formwork had been shifting around a bit. We were seeing certain areas needed additional support as well as some repair work,” Hernandez said. “That also forced us to go back and look at what we’ve installed in the ground. Fortunately, we only had installed 42 pilings of that style.”

Driving the piling the 120 to 130 feet deep into the sound bed might seem like a straightforward operation: A gigantic weight falls through a shaft, striking the piling, then hydraulics lift the weight before it falls again and again until the piling is at the right depth. It is, however, far more complex than that.

Electronic sensors monitor the force of each blow to the pile and how many times it’s struck. There are also handwritten observations as the crew looks for potential problems.

“Fortunately, all of that review revealed that we’re very confident what we’ve got is correct,” Hernandez said.

The bridge is being built from the north and from the south simultaneously, although progress on the north end is running a little behind the Rodanthe end to the south. The discovered defective pilings were supposed to go to Pea Island at the north end of the project.

Price said he was confident the north end will catch up, however, pointing out that there is a strong sense of teamwork and competition.

“No one wants to be the slowest crew,” he said.