A boatload of shingles was going down, not up. The captain feared that “Hatteras will batter us.”

This is the story of a New Year shipwreck with a happy ending, as well as an impromptu stay on Hatteras Island for the six crew members aboard the schooner Hester A. Seward. Hauling timber from South Carolina to Maryland, the voyage began with a promise, and almost ended in disaster.

The Promise

Timber has been part of South Carolina’s economy since the late seventeenth century. Over time, timber grew into a major employer with millions of dollars in invested capital that, in the process, altered the landscape of South Carolina. The hardwood trees there were prized for making durable roofing shingles. From the Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers to the Secretary of War for the Year 1895, we learn that in that year South Carolina exported 238,350 tons of timber for “shingles, cross ties & other articles” valued at $1,683,000 (over 51.5 million in today’s dollars).

The small schooner Hester A. Seward had taken on a load of these shingles in Georgetown, South Carolina, bound for roofing new houses in Baltimore, Maryland. It should have made for a Happy New Year for many new homeowners there, as well as the crew and Kirwan Brothers Company of the Hester A. Seward. But a promise is only about a potential happening.

The Ship

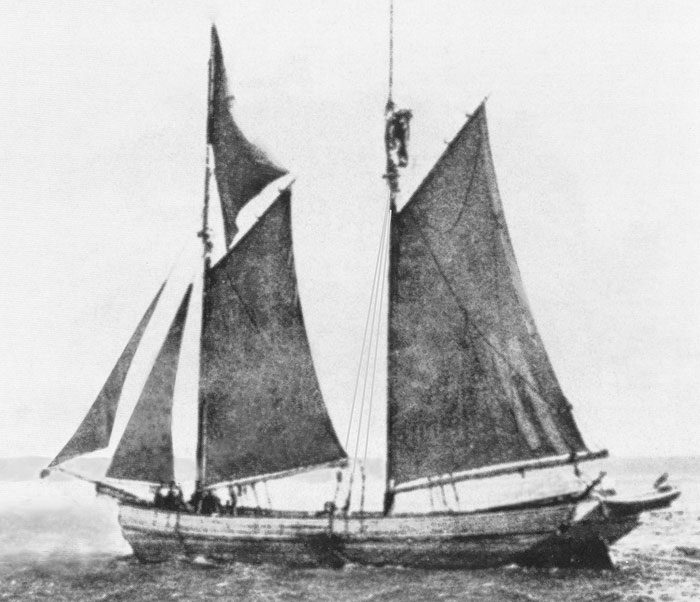

The Hester A. Steward was a small vessel, and was only a two-masted, 150-ton schooner. She was built ten years prior, in 1885, at Taylor’s Island on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay, Maryland. During its early history, Taylor’s Island was an important center for farming, ship building, and seafood. The schooner was owned by a Mister T. J. Seward, Postmaster of Hill’s Point Post Office in Dorchester County. The vessel had a home port in Baltimore. On its fateful final voyage, the Seward’s captain was Dixon Younger.

Wreck & Rescue

Amazingly, this was not the only shingle-laden small schooner owned by T. J. Seward that was lost on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The two-masted, 141-ton schooner Francis E. Waters in 1889 had also taken a cargo of Georgetown, South Carolina shingles bound for Baltimore. It was also a total wreck, this time at Nags Head, and with all lost including six lives – but that is another story!

The weather for Sunday, January 6 of 1895 off the Outer Banks was typical for that time of year. A heavy gale had sprung up, and the high winds had produced rough seas, as always. Struggling slowly against these forces on her north-bound journey, trying to clear the dangerous coast around Cape Hatteras, the Hester A. Seward finally sprang a leak. Knowing this could quickly become fatal, Captain Younger immediately ran for what he hoped would be the safety of Hatteras Inlet. But, as the merciless, shallow sands unseen below so often did, the bar there grabbed the schooner and held her stationary as a target for the pounding surf. As usual, the surf won, and the schooner sank in what turned out to be a fortunate spot, as several United States Life-Saving Service stations were nearby.

The Hatteras Inlet Station was the closest, and a surfman on beach patrol had spotted the wreck and reported it to his keeper, James W. Howard.

Score card: The Changing Names and Locations of Life-Saving Stations

Like so many other matters then and now, the United States Life-Saving Service was an evolving organization. The following were developments along the North Carolina Coast alone: the first seven stations were built in 1874; eleven more were added in 1878; between 1880 and 1888, six more were added; the final four were built during the period of 1894 to 1905, for a grand total of twenty-nine.

During those evolutions, six of the stations were renamed, (some more than once), and many were slightly relocated. Two were actually changed from one side of the inlet to the other. Hatteras Inlet station was one of those. Today, the Hatteras Inlet USCG Station is near the southern tip of the island, but the original Hatteras Inlet station was built in 1883 at the eastern end of Ocracoke Island. That is the location for this rescue. Some of the pilings for the pier of the original station are even still visible as the Hatteras-to-Ocracoke ferry arrives.

Keeper Howard instantly launched the station’s surfboat. Reaching the wreck after a four-mile rough trip, the lifesavers found that a pilot skiff had been near the wreck, and had safely taken off all six crew members.

Howard offered assistance, but it was not needed at the time. Shortly following was the arrival of the Durant Station crew from Hatteras Island in their sail-oar equipped surfboat. Keeper Zera G. Burrus of this station was requested by the Seward crew to take them to his station and, following standard procedures, they spent several days there, were quickly provided with dry clothes, and were taken care of in typical U.S. Life-Saving Service manner.

The captain and crew of the Hester A. Seward concluded with this verbatim letter of acknowledgement and thanks:

HATTERAS, NORTH CAROLINA, January 6, 1895

SIR: The master and crew of the schooner Hester A. Seward, of Baltimore, MD, who were wrecked at Hatteras Inlet on the above date, wish to express out [sic] gratitude and thanks to the keeper and crew of Durant’s Life-Saving Station for the prompt and faithful manner in which they responded in making the effort they did. Had it not been for the pilot boat he would have been of good service to us; but under the circumstances, could not reach us in time, as the pilot boat was on hand, lying in wait to pilot my schooner in. Keeper Burrus met us one-half mile from the wreck, and we were transferred to his boat, taken to Durant’s Station, kindly treated, furnished with dry clothing, and properly cared for. We hope no blame will rest on him or crew, as they did their duty. Yours truly, DIXON YOUNG, Master ; T.D. GRIFFISS, Mate.

The vessel splintered and all uninsured cargo of shingles and timbers was lost, but starting the New Year with six lives saved is a Happy New Year!