How Hurricane Irene Changed the Outer Banks, 10 Years Later

Every generation or so, the Outer Banks experiences a major storm that changes the landscape. These changes include alterations to the literal geography of the islands, for sure, but they also entail shifts in our perspectives, and in how the local community responds to storms going forward.

Hurricane Irene was one of these life-altering storms, and 10 years later, the effects of Irene are still visible, and still fresh in many locals’ memories.

Hurricane Irene made landfall on Saturday morning, August 27, at about 7:30 a.m. near Cape Lookout. Having diminished in strength from a Category 3 to a Category 1, there was widespread hope that the storm would leave behind minimal damage, like 2010’s Hurricane Earl, which had a similar path. But as Irene passed over the barrier islands and turned north, heading up the Pamlico Sound, it became clear that this would not be the case.

Hurricane Irene made landfall on Saturday morning, August 27, at about 7:30 a.m. near Cape Lookout. Having diminished in strength from a Category 3 to a Category 1, there was widespread hope that the storm would leave behind minimal damage, like 2010’s Hurricane Earl, which had a similar path. But as Irene passed over the barrier islands and turned north, heading up the Pamlico Sound, it became clear that this would not be the case.

Southern Hatteras Island and Ocracoke Island remained relatively unscathed, but in the northern villages of Avon, Rodanthe, Waves, and Salvo, (and some areas of northern Dare County), the surge was catastrophic, with up to 10-12 feet of water, per National Weather Service records.

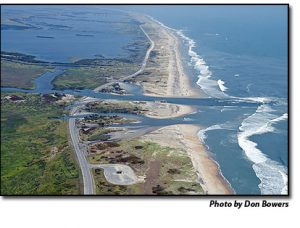

Irene cut two distinct inlets along Pea Island, created multiple dune breaches, and resulted in unprecedented soundside flooding to homes and structures in Avon and the Tri-villages. Power was tenuous for more than a week, evacuated residents weren’t able to come home for about 10 days, and N.C. Highway 12 was closed from August 27 until October 10, meaning that residents had to utilize the two-hour-long emergency ferry from Rodanthe to Stumpy Point to exit the island for seven weeks.

In the days and weeks that followed, the island was clouded in both a frustrated and shell-shocked atmosphere. Towering piles of flooded home parts lined the sides of N.C. Highway 12, and both evacuated residents and the folks who stayed vented their exasperation on how the county, state, and federal response went wrong.

In the days and weeks that followed, the island was clouded in both a frustrated and shell-shocked atmosphere. Towering piles of flooded home parts lined the sides of N.C. Highway 12, and both evacuated residents and the folks who stayed vented their exasperation on how the county, state, and federal response went wrong.

There are still small indicators of Irene’s destruction floating around Hatteras Island, such as faded signs advertising cash for salvaged materials, or waterline marks on derelict homes that were abandoned after repairs were deemed impossible. But there are much larger changes too, which are far more prominent, and which have altered the Outer Banks for the long term, and generally, for the better.

Here are just a few examples of how Irene changed our world, 10 years later.

The Captain Richard Etheridge Bridge was constructed

Though the terrain under the Captain Richard Etheridge Bridge today is mostly sand, after Hurricane Irene, this Pea Island locale was the site of a massive new inlet, that was casually dubbed “Irene’s Inlet,” or the “New, New Inlet” in local circles.

After weeks of work to reopen N.C. Highway 12, NCDOT constructed a patchwork temporary bridge with a 25 mph speed limit, known as the “Lego Bridge,” and in 2018, its permanent replacement – the Captain Richard Etheridge Bridge – was completed and opened to the public.

Category became less important, and the focus shifted to storm surge

Hurricane Irene proved that a Category 1 storm could be devastating. Leading up to Irene, most residents made their decision on whether to evacuate based on a storm’s category alone. For example, islanders might evacuate for a Category 4 or 5 storm, but would likely stay put for a Category 1 or 2.

But Irene shifted the conversation from category number to the potential for storm surge.

In September of 2012, a Town Hall Meeting was held at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras to discuss the effects of Hurricane Irene, and potential improvements going forward.

It was at this meeting that National Weather Service (NWS) representatives started to emphasize the importance of paying attention to storm surge in a hurricane forecast, as opposed to wind strength, category, and other less-important elements of Irene. Years later, the NWS would launch an interactive online storm surge map as one of its forecasting tools, and today, media outlets from the Weather Channel to local newspapers tend to concentrate on the potential for flooding during a storm, as opposed to other effects.

Dare County launched a new online hub for emergency management

Obtaining accurate and timely information was a persistent problem during Hurricane Irene, and especially for the residents who evacuated. With online resources scarce, and social media still in its infancy, it was difficult for evacuees to determine the timeline for returning, what information would be needed to board the emergency ferry, and who would be allowed to come back, (i.e., non-resident property owners versus full-time residents.)

Dare County officials took many steps to address these communication gaps, and one of the most notable changes was the launch of their “new” Dare County Emergency Management page on the county website. Dedicated to emergency incident information, from evacuation announcements to re-entry forms, the page is still a primary resource for the public to obtain information on current storms, nor’easters, and hurricanes.

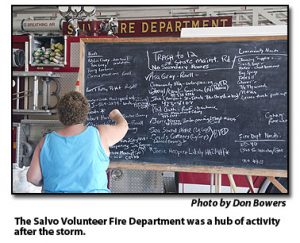

Island fire stations became the launching point for storm recovery

The local volunteer fire department stations on Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands have always been central locations for residents to gather after a storm, but after Irene, many residents did not go by the fire stations unless they needed a meal, or in Avon’s case, to check out the newly launched “Really, Really Free Market” for supplies. (10 years later, the Really, Really Free Market is still going strong, too.)

The local volunteer fire department stations on Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands have always been central locations for residents to gather after a storm, but after Irene, many residents did not go by the fire stations unless they needed a meal, or in Avon’s case, to check out the newly launched “Really, Really Free Market” for supplies. (10 years later, the Really, Really Free Market is still going strong, too.)

But at the aforementioned Town Hall Meeting post-Irene, county officials and the community at large determined that the fire stations would be a more prominent and all-encompassing site for the community to obtain assistance, with a designated county employee to coordinate long-term recovery needs, alongside other organizations and storm-response volunteers.

Today, our local fire stations are the frontlines of storm recovery efforts, with CERT, Cape Hatteras United Methodist Men, Dare County Social Services, and other volunteers coordinating the efforts to assist residents in a timely and comprehensive manner.

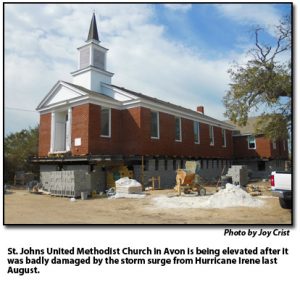

Homes and buildings started to rise

Hurricane Irene was also one of the first storms where local homes and structures began to be elevated on Hatteras Island on a large scale, as it was the first time that a number of low-lying residences on the soundside had been flooded since the big storm of 1944.

Hurricane Irene was also one of the first storms where local homes and structures began to be elevated on Hatteras Island on a large scale, as it was the first time that a number of low-lying residences on the soundside had been flooded since the big storm of 1944.

In Avon village, numerous one-story homes and buildings were raised onto pilings to protect them from future flooding events, including the St. John’s United Methodist Church in Avon, which was lifted roughly nine feet above the ground. More properties were elevated over the years, and today, Avon village is a mix of ground-level and raised properties, whereas prior to Irene, pilings were not a common sight in this primarily year-round community.

N.C. Highway 12 and ferry channels were put in the spotlight

The question of what to do about NC. Highway 12 has been lingering in the background for decades, but Hurricane Irene put more pressure on local, state, and federal entities to find long-term solutions. Several committees and task forces were formed to examine these issues after Irene, and these groups continue to exist, such as the Dare County Waterways Commission or the newly formed N.C. 12 Task Force.

The Bonner Bridge Replacement project, which had been in the works since 1993 but was bogged down by lawsuits for years, also became a more prominent goal in the Outer Banks community, and the official go-ahead to proceed was announced roughly four years after Irene in June of 2015.

Today, Hatteras Island is home to two, (and nearly three), new bridges that combine to make N.C. Highway 12 more reliable in the event of an Irene-like event, but Irene was not the first storm to drastically change the Outer Banks, and she won’t be the last.

As 2019’s Dorian proved, there will always be storms that catch the community off guard, present new challenges, and alter the landscape, again and again. The best that Outer Banks locals can hope for is that these events are remembered, dissected, and used as a launching point to create better storm responses and initiatives in the future.