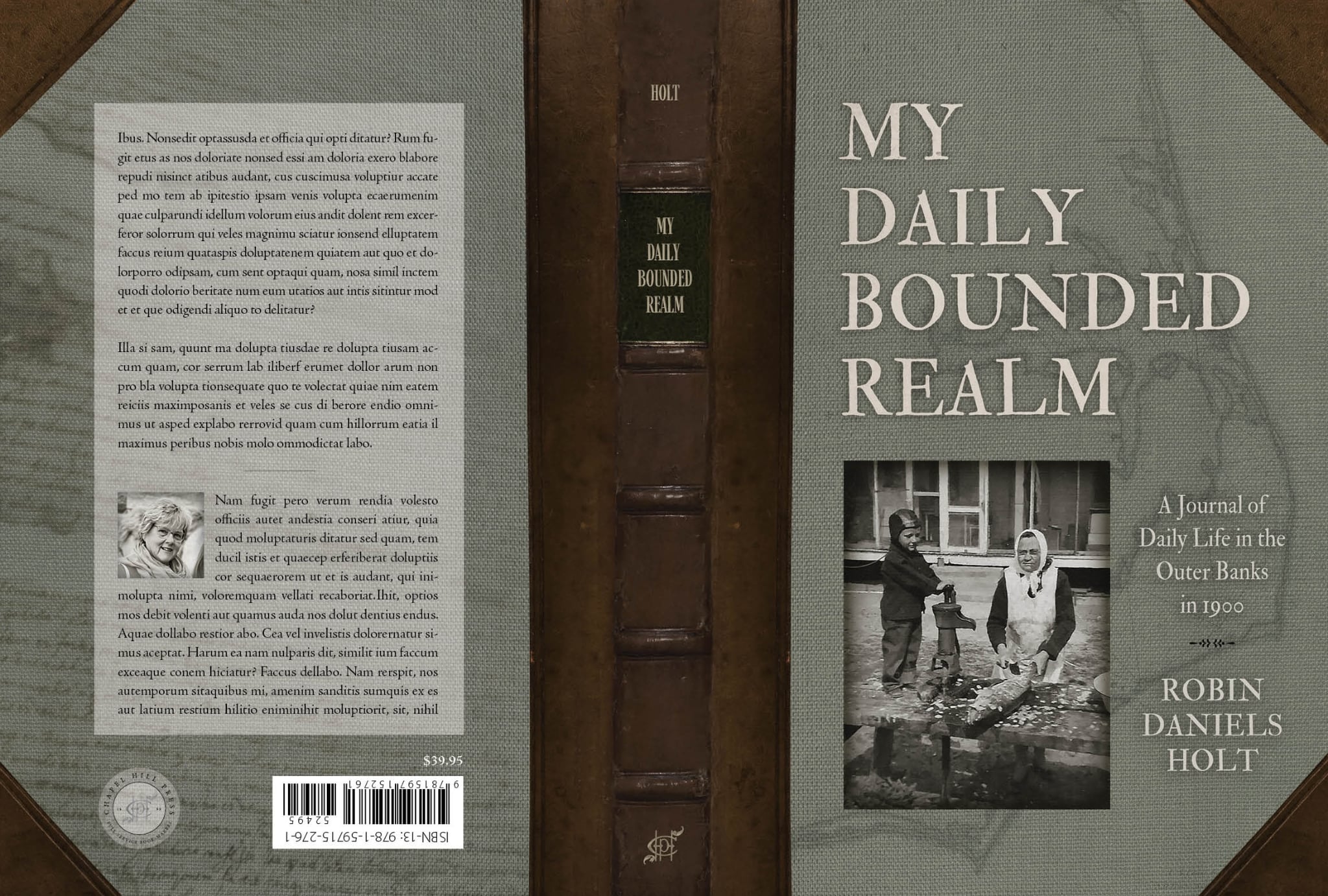

Going Native on the Outer Banks – A Step Back in Time

By Barbara Miller, Frisco Native American Museum & Natural History Center

When visiting the Outer Banks, it is easy to be in awe of our beautiful beaches, great fishing, excellent restaurants, fun water sports, and stunning sunsets. But we are here to remind you of the incredible history and stories of OBX! We have some amazing sites to see on these barrier islands that are full of historical firsts.

Long before modern visitors set foot on the beautiful wind-swept shores of Hatteras Island, the first “Outer Bankers” thrived in the coastal environment. Although much of what we know about them is based on early drawings by John White and sixteenth century records, many historians believe that Native Americans lived on coastal North Carolina as early as 500 AD; others date their appearance much earlier.

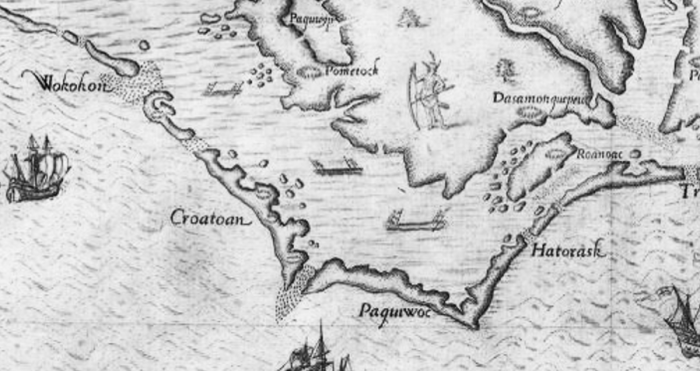

Ever wondered where Hatteras Island got its name? Along the length of Hatteras Island, there are seven villages that stand today. According to the John White map, Rodanthe, Waves, and Salvo were once home to the Hatorask Tribe, from thus “Hatteras” was derived. Traveling down to Avon, this stretch of coastal land belonged to the Paquiwoc Tribe, and continuing south you enter the areas of the Croatoan Tribe (today’s Buxton, Frisco, and Hatteras Village). If you hop over to Ocracoke, you will find there once lived the Wokokon Tribe.

All the tribes of the Outer Banks spoke languages of the Algonquian dialect, and appear to have been related. There are no reports of them fighting with each other, though some conflicts happened with inland tribes.

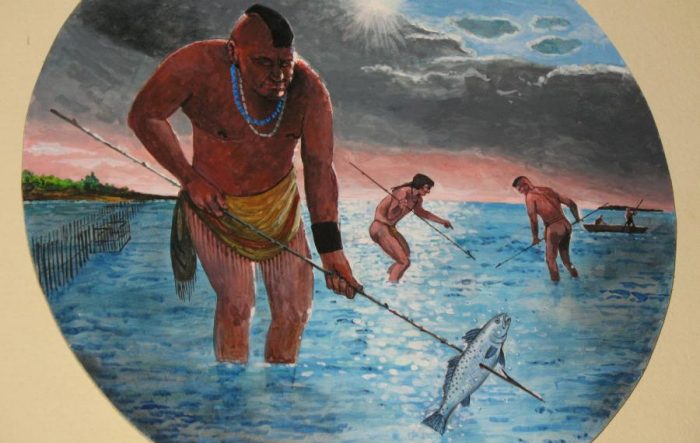

These were permanent societies growing crops, fishing, hunting, and reaping the rich resources that the land provided. Huge middens (trash mounds) of shells from oysters, clams, and scallops have been located, enabling researchers to gauge the size of the population. While numbers vary, Dr. David Phelps, East Carolina University professor and archaeologist, conducted studies on Hatteras Island in the 1990s that estimated an early population at 4,000—similar to current numbers.

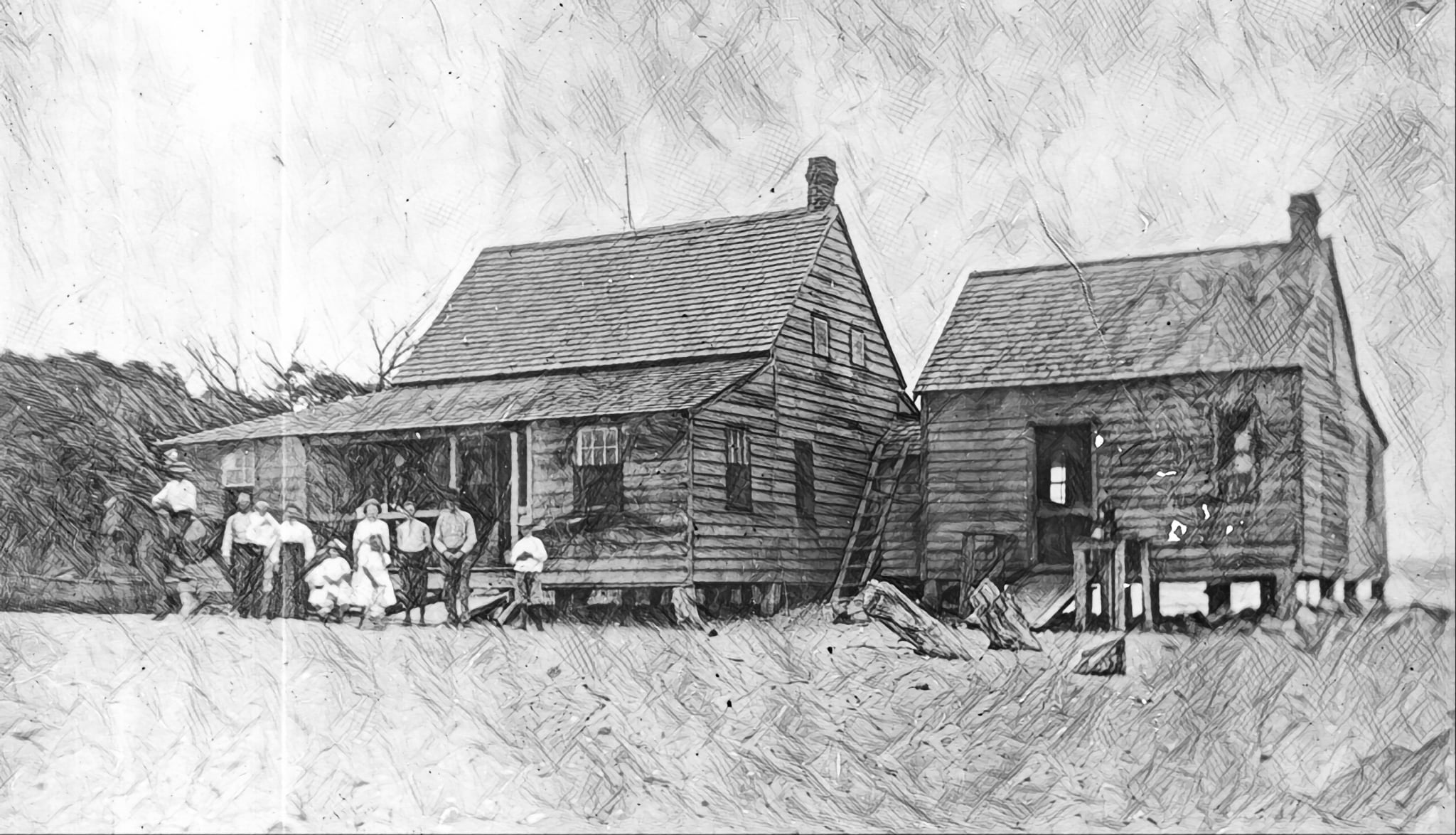

Although somewhat isolated, ancient travelers had access to Hatteras Island through an inlet just north of present-day Buxton that has long since been closed by Mother Nature. Rich fishing grounds and heavily wooded areas filled with game drew natives to the island. Evidence of several village sites have been found in present day Buxton, Frisco, and on Ocracoke Island. Early Native Americans were able to survive because they lived in harmony with their environment, recognizing the value of all living things and utilizing the gifts nature offered. The culture was sophisticated and complex, supporting an infrastructure that included hunting, fishing, trading, craft and tool production, and rotation agriculture. The people lived in “longhouses” covered by mats made by weaving Cattail stems. The simple cattail plants were used in so many ways; the flower fluff for soft padding, as fuel for starting fires, a root gel used for burns and scrapes, and 3 parts were eaten.

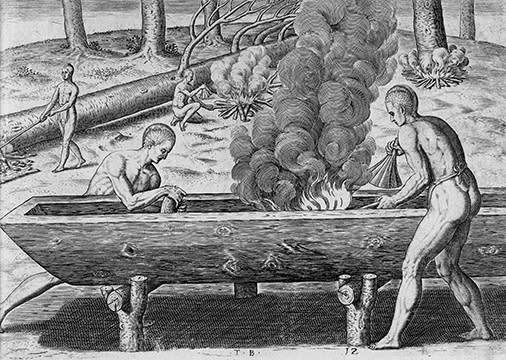

In addition to food resources, the dense forests provided a means for the original inhabitants to craft vessels that could expand their fishing area as well as take them off the island. Using cypress trees, they fashioned sturdy dugout canoes that could hold a number of people and glide swiftly and silently over sound waters. The canoes were heavy enough to handle ocean currents.

Tourists coming to Hatteras Island may be surprised to find a Native American museum, but the island is actually the site of a major historic event – the first recorded meeting between English and Native people. That fateful interaction took place in July 1584 near the present location of the Frisco Native American Museum. Records from that initial encounter indicate that the English found the natives to be “very handsome, goodly people, and in their behavior as mannerly and civil as any of Europe.” The early report also describes the clothes of the women and men as being quite similar, noting that “only women wear their hair long on both sides, and the men but on one.”

The Frisco Native American Museum & Natural History Center provides glimpses into that long-ago past.

While the museum includes nationally recognized displays on Native American cultures from across the United States, a large gallery is dedicated to the original inhabitants of the island. A life size cut-out figure of a native made from 400 year old John White drawings welcomes visitors. The tattooed and stately warrior is carrying a bow for hunting with a quiver of arrows slung over his shoulder.

Further, into the room, the dug-out canoe found on the museum property is flanked by life-size figures of an Algonquian woman and a child, both also tattooed.

The canoe shows indications of age and wear yet maintains its graceful original lines. Long, thin poles that have been shaped for spearing fish rest in the canoe and provide vivid reminders of the dexterity and skill of native fishermen. It is easy to imagine the hollowed-out and hewn log gliding silently through sound waters or resting on a sandy beach.

The gallery also includes artifacts found on the south end of Hatteras Island as well as items uncovered by Hurricane Emily in 1993 in present-day Buxton.

Recognizing the importance of the items exposed by the storm, the museum conducted several seminars to build a base of support for further exploration of the area. As a result, East Carolina University conducted a number of summer archaeological digs in the Buxton area. Items from those projects are also on display.

It is impossible for a museum to tell the complete history of any culture, but the Hatteras Island gallery in the Frisco Native American Museum & Natural History Center opens a small window to an ancient world that still ignites the imagination and inspires interest and concern. That ancient world merges with the present when museum visitors participate in workshops, special programs, or volunteer opportunities that are designed to keep old traditions alive.

————-