Never again will there be a beachcomber’s haul on the Outer Banks – or anywhere – to match what Nellie Myrtle Pridgen collected in a lifetime that straddled World War II and the banks’ nascent tourism industry. Her astonishing collection has been housed in a small museum inside the Mattie Midgette Store in Nags Head, where she had lived, but the building is rarely open to the public.

It’s past time to change that, say the proprietors of the Outer Banks Beachcomber Museum, who have recently launched a crowd-funding effort so the museum can be opened year-round. The goal is to purchase the undeveloped property behind the store and relocate the building and the 1933 family house farther from the beach. The site would also provide more parking for visitors, an issue that has stymied accessibility to the museum since it first opened 14 years ago, and opened sporadically since then.

“We’re not coming at this empty-handed,” said Chaz Winkler, who lives above the museum with his partner, Dorothy Hope, owner of the building. “We have the most significant cultural asset on the northern Outer Banks. There’s nothing like it. It’s true authentic history that’s important.”

The 1914 store, listed in 2004 on the National Register of Historic Places, had been the centerpiece of the soundside community of Old Nags Head, serving the earliest tourists who flocked to the beach for the salt air. Later, it was moved to its current location across from the ocean, where the store remained open until the 1970s to serve the growing summer population who stayed in nearby oceanfront cottages – now the Nags Head Beach Cottage Row Historic District.

A self-taught environmentalist and notoriously unforgiving tourist scold, Nellie Myrtle, as everyone called her, obsessively roamed the beach for decades, when the surf still coughed up remnants of wars, pirates, shipwrecks and European exploration. Up at dawn, she had little to no competition. Her best days were when she caught low tide in early morning, and again at dusk. Nellie Myrtle gathered every bit she deemed interesting, which she stuffed into her large pants pockets or on especially fruitful days, tossed into a plastic grocery bag.

“The entire collection is like a microcosm of what went on in history between 1930 and 1980,” said Richard LaMotte,” author of “Pure Sea Glass, Discovering Nature’s Vanishing Gems,” a reference book for beachcombers published in 2004, and “The Lure of Sea Glass” published in 2015. “The relics that she found are not only extremely rare, they’re components of that era. “

Coastal geologist Stan Riggs, with East Carolina University, saw the collection as a reflection of supply as much as a window of opportunity that has closed forever.

“The possibility of finding the kinds of things she found is impossible – even after a storm,” he said after visiting the museum in the mid-2000s.

In a recent telephone interview from his Maryland home, LaMotte said he believes the museum’s collection would be an enormous success if it were arranged with better flow in the new location, with revolving displays added of beachcombing finds from from other states and countries.

Nellie Myrtle’s bounty had captured a unique time at a uniquely exposed location on the coast near the mighty Gulf Stream and the infamous Graveyard of the Atlantic. With Nags Head about the midpoint on the barrier islands, storms would often churn up the sea floor, casting sea glass and odd toys from the ocean to join exotic shells and skeletons of sea creatures in the beach wrack. And Nell would be there at the first light to scoop it up.

She also witnessed firsthand the devastation of the U-boat campaign off the Outer Banks in 1942. German submarines, or U-boats, targeted Allied merchant shipping off the North Carolina coast, sinking nearly 400 ships in the area that became known as Torpedo Alley.

One photograph she took of oil from a shipwreck spoiling the beach was published in National Geographic magazine.

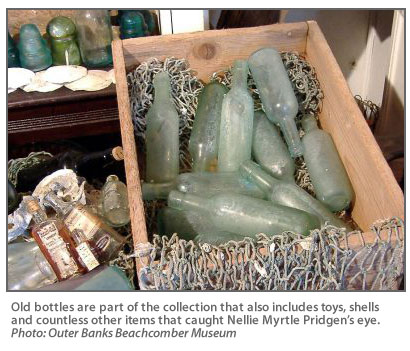

When she died in 1992 at age 74, Nellie Myrtle left behind an enormous collection of sea glass, sorted by color; rare sea shells; old dolls and children’s toys; military gear; old coins, arrowheads, glass bottles; lightning glass, including one piece the size of a bicycle wheel; fishing gear and buoys – literally decades of detritus tossed from the sea or unburied from wind-blown dunes.

She didn’t just collect things, she also collected every tidbit of knowledge she could glean about the ocean and the environment. A big reader, she clipped newspaper articles constantly and read scientific books and journals.

“It’s phenomenal,” said Nags Head Mayor Pro Tem Susie Walters, a 33-year resident. “The fact that she found all those items and was able to research them through National Geographic, it was incredible.”

In her later years, when more tourists starting invading “her” beach, Nellie Myrtle became a stalwart guardian of the beach and the ocean, to the point where she could be aggressive, even nasty.

The late Outer Banks author and historian David Stick, who grew up with Nellie Myrtle, recalled in a April 2006 essay that “thin and wiry” Nellie Myrtle was known to be “unfriendly” and “caustic in her comments,” but she was also witty and possessed “remarkably broad knowledge.”

She started her life on the sound side, where her mother “Miss Mattie” had opened her general store at age 17 to serve the wealthy visitors who summered in Nags Head – one of the best examples of entrepreneurial foresight on the Outer Banks. Her father Jethro was a commercial fisherman, and she had a brother, Jethro Jr. In the 1930s, the family rolled the store across the sand to the ocean side – another brilliant business decision.

A neighbor in the oceanfront cottage across the road from the store who was also named Mattie, dubbed Miss Mattie “Peach,” – she reportedly had big rosy cheeks – and the nickname stuck.

Nell eventually had two unsuccessful marriages and two children, Elwood and Carmen. During the war, she worked as a hydraulic mechanic for the Navy in Norfolk during the week, while Peach watched her children. After the war, Nell opened a boarding house in the big house, with her parents living above the store. After Miss Mattie died in 1972, Nell moved into the apartment above the store, where she lived for the rest of her life. Despite her love of walking, she was a smoker and suffered at least three heart attacks.

It took Carmen Gray, Nell’s daughter who died in 2007, an entire decade to sort and organize her mother’s collection, with the help of Winkler and Hope, who was a close friend of Gray’s. Button Daniels, also a founder of the museum and a Wanchese native, also helped. The first time most fellow Nags Headers saw the collection was the day the museum opened in 2002.

“Next to Jockey’s Ridge and the Wright Brothers Memorial, it is the most historically significant place on the northern Outer Banks,” Stick said about the museum in a 2004 article in The Virginian-Pilot. “It is an integral part of the Nags Head Historic District.”

Hope, who had bought the property from Gray, said she is trying to work with the town of Nags Head to resolve zoning difficulties that go back to the days Gray owned the buildings. The conflict centered on parking requirements that the museum founders felt were unreasonably strict for a historic structure and would destroy the integrity of the building.

For years, the museum has opened to the public only on a few weekends a year. But Hope said, with the recently renewed dialogue, she is optimistic that a solution can be found so it can open year-round.

As one of the founders of the museum, Daniels sees the effort as a chance to save what’s left of the heritage of old Nags Head.

“Our goal is to preserve this,” Daniels said. “With help from people – because we can’t do this by ourselves – we want to open it back up, for all those people who haven’t been able to come this summer. I just love it when people come in and say ‘I remember that!’”

Andy Garman, Nags Head deputy town manager, said that he believes that the museum would be able to qualify as an owner-occupied gallery/museum, which has minimal requirements for parking. The fire marshal and the building inspector would also have to inspect for basic safety requirements, such as exit lights and fire extinguishers.

Garman said that preservation is a concern in the town’s new comprehensive plan now in the works.

“We do acknowledge the museum being an important cultural resource,” he said, adding that the plan recognizes its “extraordinary and diverse collection of seaside relics.”

Walters is a member of one of the advisory panels looking at the town’s land-use plan, ordinances and other issues with development.

“We have discussed legacy buildings and things that need to be preserved,” she said. “We do understand the importance of some structures in Nags Head that really are pure treasures.”

And in a way, Nellie Myrtle’s eclectic collection is the best souvenir of Nags Head anyone could ask for.

“I really, really hope it comes together before it is lost,” said Walters.

OCTOBER 8 OPEN HOUSE

The Outer Banks Beachcomber Museum will hold its annual Columbus Day weekend open house 10 a.m.-4 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 8. Admission is free. The museum is at 4008 South Virginia Dare Trail in Nags Head

(This article is provided by Coastal Review Online, an online news service covering North Carolina’s coast. Sam Walker is a reporter for the Outer Banks Voice. For more news, features, and information about the coast, go to www.coastalreview.org.)