Gill net closure delivers a tough economic blow to local fishermen By JORDAN TOMBERLIN

When the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries announced that, effective Sept. 26, 2012 at 10 a.m., the shallow waters of the Pamlico Sound would close to large-mesh gill net operations in an effort to protect threatened and endangered sea turtles, the regulators effectively shut down the commercial southern flounder fishery for the remainder of the year.

The fishery, which operates under a highly-monitored permit system, can be closed when the number of encounters between turtles and nets exceeds prescribed limits.

This year, four interactions were observed, a number that was sufficient to prompt the fishery closure.

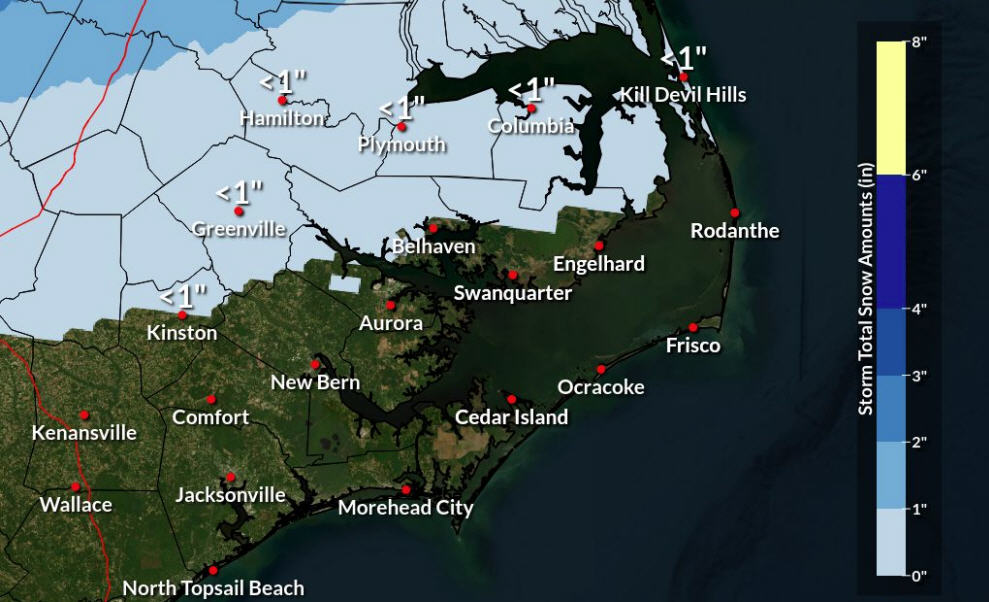

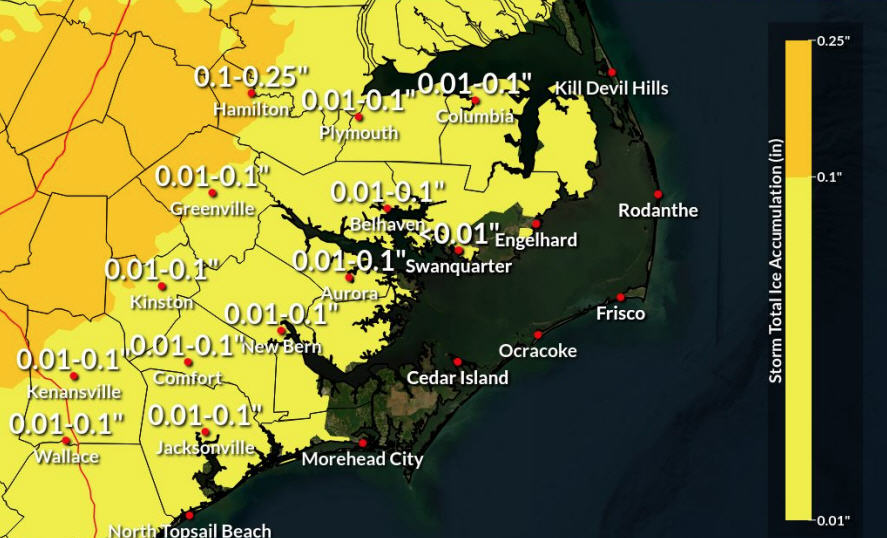

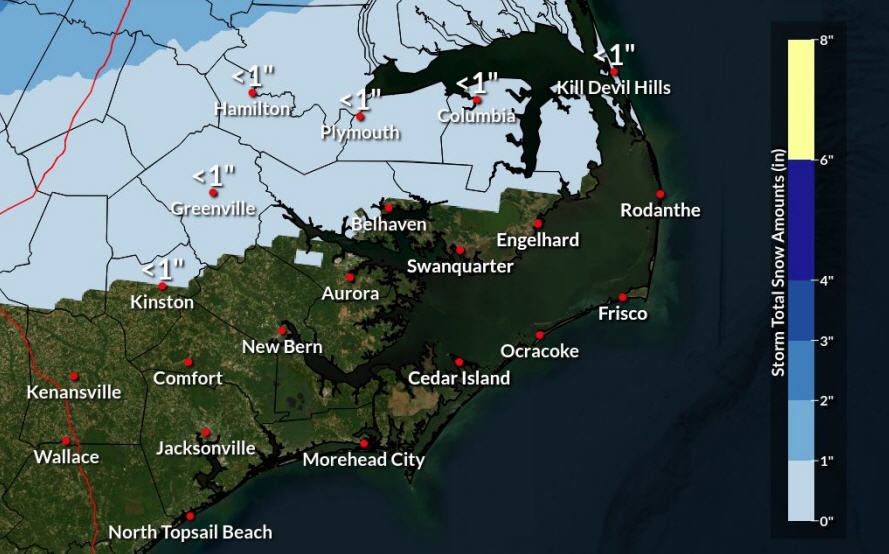

Two interactions involving live green turtles were reported near Rodanthe on Sept. 21, and two interactions involving endangered Kemp’s ridley turtles—one live and one dead—were reported near mainland Hyde County on Sept. 20.

A few days later, announcement of the closure came down from state officials.

The closure was unexpected, and it’s hitting local fishermen where it hurts them most—their pocketbooks.

“Bottom line,” said Steve Bailey, a commercial fisherman and the owner of Risky Business Seafood, “[this closure] is going to cost me about $20,000.”

Bailey said that he sets nets every day during the flounder season, and, in addition to selling the flounder in his seafood market, he said his business aims to put away several thousand pounds of the fish each season.

But that won’t happen this year. Not if the closure isn’t reversed. And many other local fishermen, Bailey said, will have it much worse.

“I’m going to make it,” Bailey said. “But there are a lot of guys around here who, fishing is all they do, and it’s really going to hurt them.”

Tony Burbank, another local commercial fisherman, who also works Avon Seafood in Hatteras, said he estimates that he will lose about $1,000 per week as a result of the closure. He also said that, through is work at the fish house, he knows of at least seven or eight other fishermen who will lose the same.

Given that the commercial harvest of southern flounder closes statewide on December 1, the most recent closure will—if it isn’t reversed—mean that each of those fishermen will take an estimated $9,000 loss.

When you consider the wider impacts of that—a reduction in fish-house profits, fewer hours for fish house employees, and a loss of stock for retailers like Bailey—you’re looking at an estimated loss upwards of $100,000. And that’s a significant amount of money, especially for a community about to enter the economic doldrums of winter.

Not only is that a significant loss at a really bad time, it’s essentially money that can’t really be reclaimed elsewhere.

Southern flounder—essentially the only species targeted by large-mesh gill net operations in the Pamlico Sound—are highly seasonal, and they spend their fall feeding in the warm, shallow waters of the sound before they are pushed out into the ocean by annual drops in water temperature.

“Flounder are very seasonal,” Bailey explained. “Nature tells them when it’s time to for them to go in the ocean,” he said. And once that happens, it won’t matter whether the fishery is open or not—there won’t be anything for them to catch.

“It would be like telling a charter fisherman that he can run trips January through March, but not May through July.”

The problem is that federally-protected sea turtles apparently march to the same biological drumbeat as the flounder, hanging out back in the sound, feeding and enjoying the warm waters, until cooler temperatures move them out to the ocean.

It’s hardly surprising then, that sea turtles and flounder nets occasionally come into contact. And it is perhaps equally unsurprising that these encounters prompted lawsuits and restrictions aimed at ensuring the safety of sea turtles—all species of which are federally listed as either threatened or endangered.

In 1999, as a result of “several instances of fishery interactions with threatened and endangered sea turtles,” the Pamlico Sound large-mesh gill net fishery was closed completely from Sept. 1 through Nov. 30, by federal rule.

However, the following year, the National Marine Fisheries Service set up a system that allowed gill net fishermen to access limited areas of the fishery during the closure.

That system relied on a series of what’s known as incidental take permits—which allow for limited takes of threatened or endangered species in the course of otherwise lawful activity—and required that the fishery be highly monitored, both through self-reporting practices and government observations.

Under this system, every fisherman granted a permit to fish during the closure is required to report each week how many yards of net he fishes, as well as any interactions he has with sea turtles.

In addition, he must allow any of the 10 to 15 state observers that monitor the fishery to accompany him on a trip, any time one asks to go. Failure to allow an observer on the boat could result in revocation of the permit.

The system allowed for a certain number of interactions with sea turtles.

These total allowable catch numbers reflect the estimated number of interactions the Marine Fisheries Service expects to occur between turtles and fishermen, based on observed or reported interactions from previous years.

If the number of interactions that observers report exceeds the number allowed under the permit, then the fishery has to be shut down.

This year, there were actually no official regulations. North Carolina’s incidental take permit expired Dec. 31, 2010, and the application for renewal has been under review since May of that year.

The National Marine Fisheries service allowed the state to operate under the provisions specified in their application. However, the National Marine Fisheries Service requested more information from the state, and when the state re-filed its permit application on Sept. 6 of this year, regulators included lower available catch numbers for the fishery.

Under those most recent catch limits, fishermen are allowed 173 interactions between live green turtles and 86 interactions with dead green turtles; 16 interactions between live Kemp’s ridley turtles and eight interactions with dead Kemp’s ridley turtles.

It was on those numbers that the fishery was operating when the four interactions that prompted the fishery closure were observed.

“The dead Kemp’s ridley is what gave us the most trouble,” said Chris Batsavage, chief of the Protected Resources Section at the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries.

“It was definitely a worst-case scenario that we encountered a dead Kemp’s ridley in the first week [of observations].”

It was a worst-case scenario indeed.

Because of the fact that observers can’t be on every boat that fishes, every day that it goes out, Marine Fisheries has an “extrapolation” process that essentially determines—based on the percentage of the fishery that is observed—how many interactions they’re not observing for every interaction that they see.

The total number obtained from that process is what goes against the allowable catch.

For example, if an observer sees one dead Kemp’s ridley turtle, and the fishery is operating at 50 percent coverage, that one dead turtle counts as two dead turtles.

However, if the fishery is operating at 10 percent coverage—as it was on Sept. 21—then that one dead Kemp’s ridley counts as 10.

The other part of this “worst-case scenario” situation was the recent reduction in the total allowable interactions for dead Kemp’s ridley turtles—from 14 to eight under the new permit guidelines.

Essentially, that one turtle counted as 10, and the fishery was allowed only eight.

“This is the earliest we’ve ever had to close it,” Batsavage said, “but it has happened a couple times before.”

Batsavage said there’s a chance the fishery will re-open this year, but few fishermen have expressed much hope that it will.

“It would definitely help us out,” Bailey said, “but I just don’t see it happening.”

According to Batsavage, the decision will depend on observation of water temperatures, as well as reports of turtle sightings from field staff and other observers working in the sound. He was not specific about when, or if, the closure would be re-evaluated.