The Story Behind those Orange Boxes on the Islands By JOY CRIST

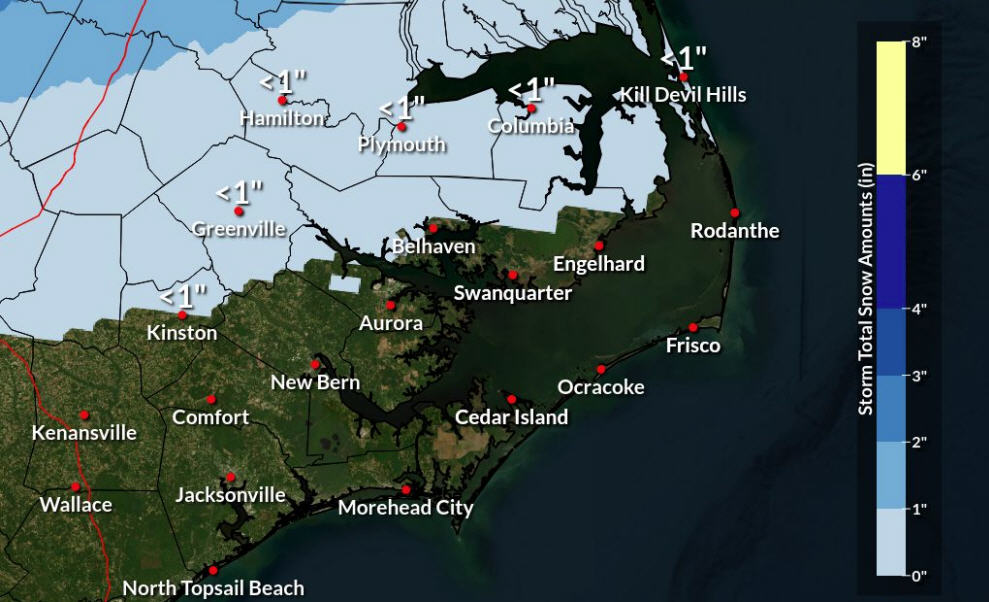

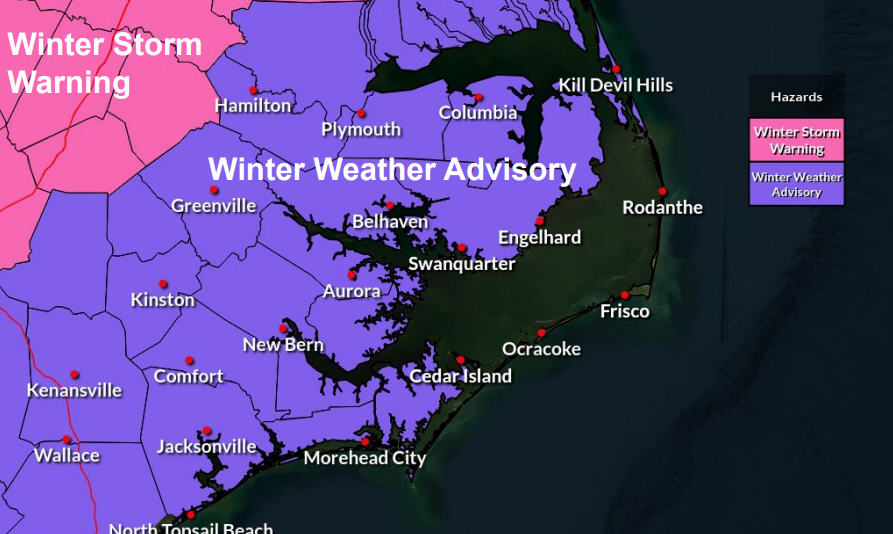

Travelers with a keen eye along Highway 12 may have noticed flashes of bright orange in the bushes, trees and beaches that line the road. Located from Nags Head all the way to Ocracoke Island, these small receptacles that resemble a mini-pup tent are part of the efforts of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture (NCDA) and Consumer Services’ Plant Industry Division to monitor and control the gypsy moth population.

“We have 20,000 of these traps across the state, and we put them in areas where the gypsy moth population is denser,” says Chris Elder, gypsy moth program manager in the Plant Industry Division. “There’s probably several hundred traps in between Ocracoke and Nags Head.”

Each trap emits a scent similar to the pheromones that female gypsy moths give off to attract their male counterparts. The males are subsequently drawn in, and get stuck in the interior of the small traps – formally known as Delta Traps – which are lined with a sticky material.

“They are not toxic to humans or other animals at all, and humans will not pick up on the smell,” says Elder. “But they are sticky inside, so people will want to keep their hands away from the traps.”

The purpose of these Delta traps is twofold. For one thing, each trap can hold a small amount of gypsy moths, which can potentially put a minor dent in the population, if needed. In addition, the traps help the Plant Industry Division survey and monitor how effective recent gypsy moth treatments have been in controlling and curtailing the population.

In 2015, an isolated infestation was reported in Buxton Woods State Reserve area of Buxton and Frisco – an infestation that threatened the maritime forest’s live oak trees with defoliation and eventually death. Gypsy moths feed particularly on live oaks on Hatteras Island, and heavy defoliation was observed on many of the live oaks in Buxton when the infestation occurred several years ago.

Most of the damage is done by the larval stage of the gypsy moth, which is a caterpillar. When the caterpillars hatch in the spring, they spread out and feed on the leaves. “That’s what happened down in Buxton in 2015 when we found the population there,” says Elder. “We intervened to keep that from happening, and we hope to eradicate this population. There was no [infestation] in 2016 and 2017 due to treatments, and this year we wanted to make sure that after Hurricane Matthew, which caused additional damage to the [local foliage], that the trees weren’t even more stressed.”

The gypsy moth, which is officially known as Lymantria dispar, is an invasive forest pest from Europe and Asia that was first introduced in the U.S. in Massachusetts in 1869. Since then, the moths have been slowly spreading south and west and can be spread via vehicles, trailers, and other outdoor equipment.

The entire state of North Carolina has been surveyed for gypsy moths since 1982. Since then, more than 100 intervention programs have been initiated to either eradicate isolated populations or suppress populations close to the leading edge of the gypsy moth’s advancing front.

In April, the NCDA contracted with a helicopter to treat 750 acres of area in Buxton three times. At roughly the same time, the orange Delta traps made their appearance along the island.

The traps will stay in place until early August, when they will be collected and reviewed to monitor the effectiveness of the treatments, and to determine the current gypsy moth population in the region. Most of the traps are located along the highway, which means that visitors with an attention to detail may be able to spot them while cruising along the island.

“They’re basically used as a follow-up to gauge the effectiveness [of our treatments] and to see if that population has spread,” says Elder. “Hopefully they are not intrusive to people, but it’s important to do this survey work to make sure the Outer Banks is OK.”