Hatteras Island Life: Riding out the Storm

Baxter Benjamin Miller stood 6 feet 8 inches tall with hands the size of a dinner plate. Almost every story I can recall about him begins this way, describing his physical stature, the size of his hands, his strength, fearlessness and stubbornness compared to that of an ox. He used every ounce of it he had. Stormy day after stormy night, he led his lifesaving crew into the deep, dark, violent unknown risking their lives in the service of saving passengers from vessels wrecked helplessly upon angry shoals, beaten weak by bitter currents.

Like so many who call Hatteras Island home, the weather shaped my great-grandfather. His pensive nature, his blistered, calloused hands, his courageousness, by all accounts, mirrored the petulant storms that have brewed for centuries over the Diamond Shoals. The weather defined his life, his character, his purpose. For the better part of my life, because of him, I’ve been on a mission to understand how the forces of nature shape a place and a people and to understand what a storm feels like on the edge of the earth.

This is a story about a few of the men and women whose home is a fleeting sandbar; whose lives are dictated by the wind and the water; whose resolves are unshakable. These are the men and women who have weathered the storm.

The moment you turn right onto Highway 12 South at Whalebone Junction, one of North Carolina’s most scenic byways, you feel as if you’re leaving a world behind. The breeze gently tugs at your car and egrets flank the pristine marshlands to your right. At golden hour, Bodie Island Lighthouse pierces through a radiant sunset. One last curve of Highway 12 South, and she appears: the criticized, condemned, celebrated and soon-to-be-replaced Bonner Bridge, your ticket across one of the most tumultuous and dynamic inlets on the east coast, Oregon Inlet. At the bridge’s crest, the curve of the earth extends in all directions. The world ahead, Hatteras Island, seems boundless, filled with possibility, adventure and freedom.

Stretching 48 miles from Oregon Inlet to Hatteras Inlet, Hatteras Island makes up almost the entire southern half of North Carolina’s Outer Banks; it’s the heart of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore and home to seven villages: Rodanthe, Waves, Salvo, Avon, Buxton, Frisco and Hatteras. It is miraculous, really: a simple sandbar, three miles wide at its widest point, posed between two mighty bodies of water – the Atlantic Ocean and the Pamlico Sound. This thin, sliver of sand stands sentry to the mainland against an often destructive and angry sea. Resolute, yet adaptive, the island is ever-shifting with the wind and tide, breaching periodically to cut new inlets that can close just as quickly as they open.

Hatteras Island is home to, arguably, North Carolina’s most recognizable feature on a map: the protruding elbow that reaches far east into the Atlantic. David Stick, the premier Outer Banks historian, describes that at the Cape, more familiarly known as The Point, “The Banks jut out so far into the Atlantic that the Gulf Stream currents caress the shoals, warming the atmosphere… Here the northbound Gulf Stream swerves out to sea as it encounters the cold waters coming down from the Labrador Current, and at the junction of the two is Diamond Shoals, the Graveyard of the Atlantic, a point of constant turbulence and of countless shipwrecks.”

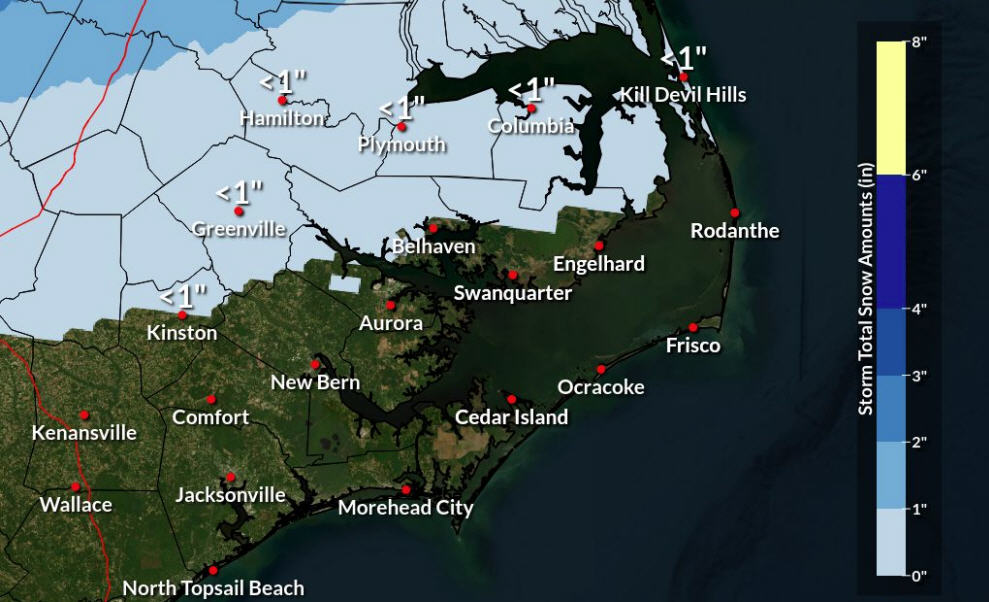

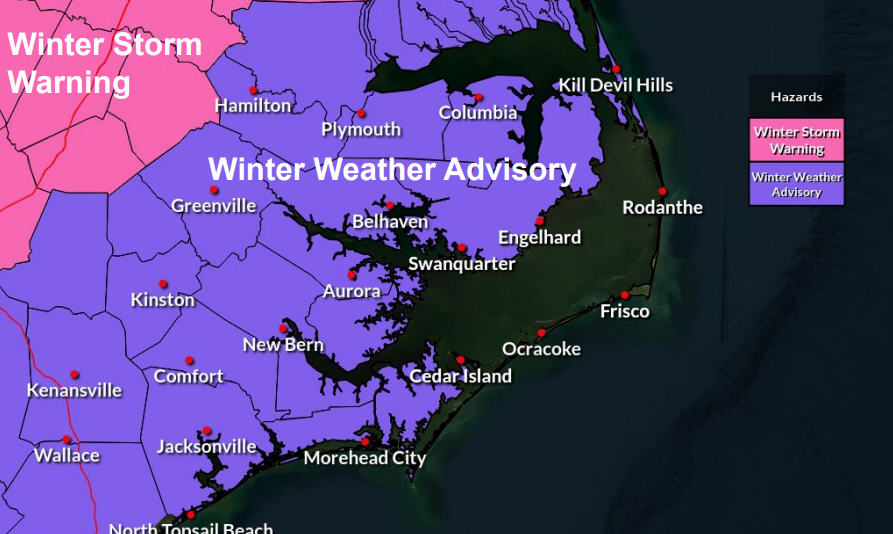

This convergence creates an ecosystem of marine life from southern and northern latitudes, representing one of the few places in the world where such different species, like warm-water dolphin and cold-water tuna, can cohabitate. It also produces unpredictable wind patterns that forecasters for the U.S. Navy in Norfolk, who are responsible for routing ships safely through the Atlantic, often underestimate.

Jan DeBlieu, native Outer Banker and author of “Wind: How the Flow of Air Has Shaped Life, Myth and The Land,” reports, “‘Something happens out there, some local phenomenon that we’re just missing,’ one meteorologist told me. ‘The wind speeds we predict will be off by ten or fifteen miles per hour, sometimes more. It’s got to have something to do with the temperature difference between the Gulf Stream and the cooler water along the coast. But in terms of sea conditions, it makes a huge difference.”

You can see the wind everywhere here. You can see it in the intensity of the weather: in the storm that moves in from miles offshore in minutes, engulfing you in its rapture. You can read it on people’s faces: a light breeze has the ability to heal, while a strong northeast blow is a humbling reminder of mankind’s insignificance.

And when you can’t see it, you can feel it in the sand biting at your ankles, and you can hear it in the yaupon trees hugging the sound, themselves bent and shaped by a powerful, persistent force. This island was formed by and revolves around the wind–its direction, its strength, its mood, its relationship with the ocean determines life here.

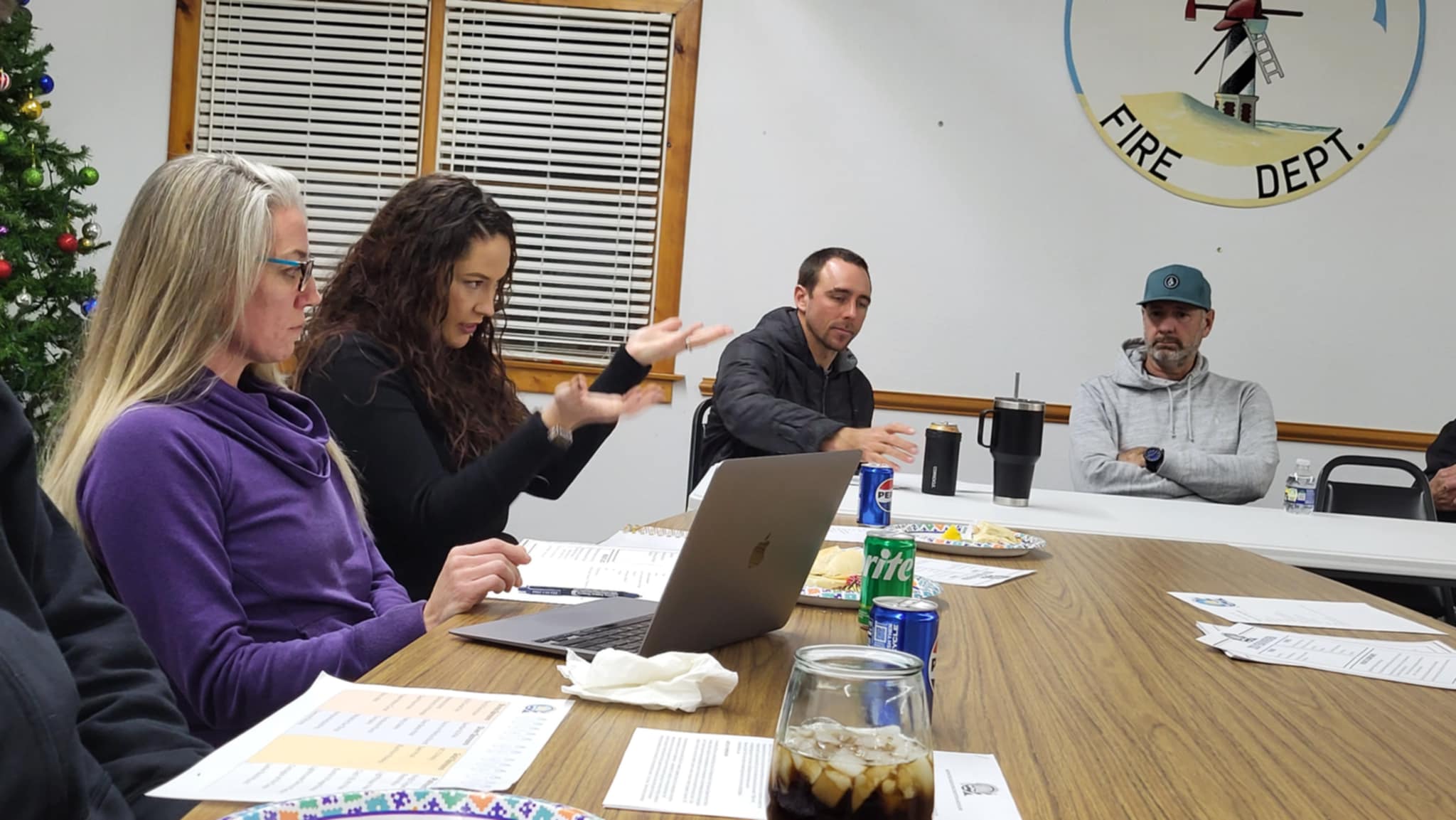

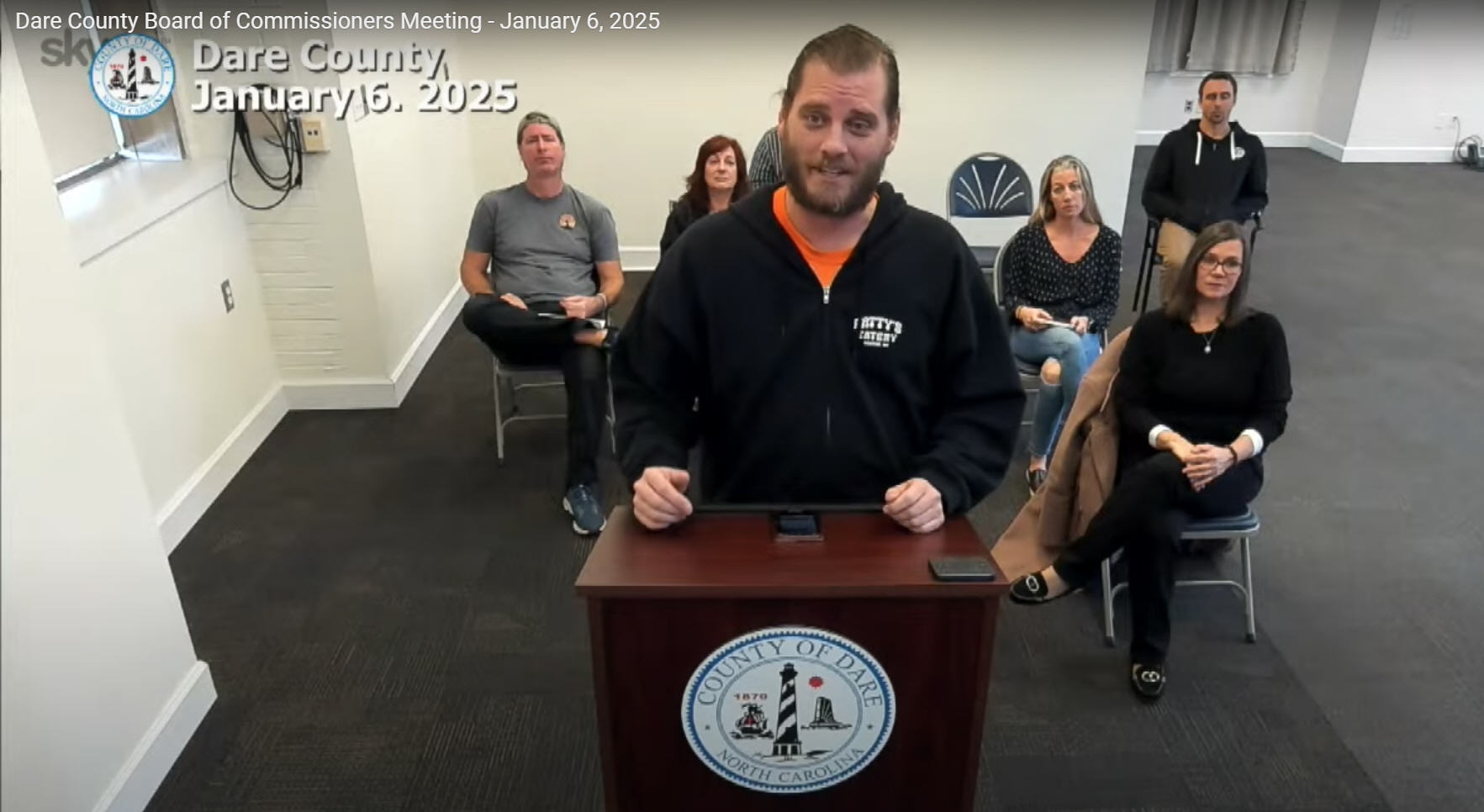

The day before I pulled up to Todd Ballance’s house in Hatteras Village, gray skies had engulfed the Island and intermittent bands of rain moved in across the horizon with a steady wind from the northeast. I walked under the stilted house, where Todd, who is a commercial fisherman and the chief of Hatteras Village’s Volunteer Fire Department, was repairing pound nets strung between two wooden posts.

“How about this weather?” I asked him.

Pausing to shake my hand, “Bad for me and good for you,” he replied. “If I could get out to set my nets, I wouldn’t be able to meet you. No nets means no money. And, it looks like this low’s going to hang around for awhile, too.”

As a commercial pound net fisherman, his livelihood depends on the weather. Like so many watermen on Hatteras Island, predicting the weather comes as naturally as hauling in the day’s catch. Throughout history and prior to modern technology, mariners have relied on observations of the wind, sea swells and currents, clouds, celestial signs, atmospheric colors, smells and animal behavior to forecast weather. Learned, genetic, or a product of patient observation, the ability of many Hatteras Island natives to read and understand the weather is almost a surreal phenomenon.

Todd, a descendent of a multi-generational Hatteras family, was raised on reading weather patterns that, today, help inform how he and his family prepare for storms. “We make decisions about when and how we’re going to prepare [for storms] from past experience and looking at the weather to see what size the storm is going to be,” he says. “And when I say weather, I don’t mean the forecast. I’m looking at barometric pressure to see where the lows are going to be – the lows coming off of Florida – and ‘Is there a high pressure that’s going to come down off the jet stream and suck it right up to us?’ I’m reading all of that and the water temperature, air temperature, wind direction, the wind shear – all that stuff makes a big difference.”

PREPARING FOR THE STORM

Storm preparation across the villages is no less of an art form than storm prediction. It’s always been this way.

Todd and his wife, Mary Ellon, explain, “When there’s a late season storm coming, we have to start deciding: ‘Are we going to pull [the pound nets]? It’s a three-day commitment to pick everything up out of the water and loss of income, [but] if you leave them out and a storm comes, too bad. You’re probably going to get wiped out.”

“We took a chance one year and left them out in a small storm with just 60 mph winds, and we got destroyed,” Mary Ellon remembers. “We found three sets of stairs that were racked up in one of the leads and tore it all to pieces. It’s your livelihood, so there’s a lot you have to think about and prepare for.”

This is one of many calculations Bankers make for a storm. They choose how to prepare their homes, whether to close up business and the ultimate choice – whether or not to evacuate. Each storm brings different variables to consider and Islanders have balanced these choices for generations.

“What you see from those who have experienced it before, is a very focused preparation,” says Ernie Foster, captain and owner of the Albatross Fleet, which gave birth to the charter fishing industry in the Outer Banks. “You get ready, you tie everything down, you batten down all the hatches. You do all the prep work with great focus, and then you’re ready. When the storm hits you go inside you and stay inside until the worst of it’s over.”

Because of sage experience and calculated preparation, islanders live with and experience storms in a rational and pragmatic manner. Ernie’s childhood home had two stoppers under the interior steps. “The purpose of the stoppers was literally to let the water in so [the house] wouldn’t float,” he explains. “It was a very practical, pragmatic thing to do. The tide would come up and the tide would come down; the worry was when to start cleaning. But what I remember is when you got six inches to a foot of water in the house, it didn’t shake as bad – and that was good.”

Everyone on Hatteras Island abides by a similar routine when preparing for a hurricane: take care of your business, then tend to your home; start outside and work your way in. There’s no time to think about the big picture or what might happen over the next few days – there’s too much work to be done.

Natalie Perry Kavanagh, co-owner of Frisco Rod and Gun, echoes this sentiment. “Preparing for a storm is pretty methodical. You calmly go through each step and mark it off the list. You get your insurance papers together. You put family photos in a plastic bag that you can grab in a hurry if you need to. Get your business settled and then get your house settled. And then you wait. A whole lot of waiting.”

While this scenario seems to play out across the coast of North Carolina, preparation feels different here because of it’s location and the character of its people. In Hatteras Blues, Tom Carlson describes Outer Banks people as “Hardworking and loyal… and stunningly selfless when such is called for. But, at the same time, these same people are fiercely headstrong, independent… and often sleeve-rolling angry with unethical bullshit. What’s right is right.”

Traits that likely stem from generations of geographic isolation and an understood interdependence and mutual respect throughout the community. While the island has become more accessible since Highway 12 was built in 1953 and Bonner Bridge was erected in 1963, the southernmost village, Hatteras, is still one-and-a-half hours from the mainland and three hours from the nearest major city, Norfolk, Va.

People have learned to be independent out of necessity. Irene Nolan, editor of the Island Free Press and Frisco resident, admits, “Believe me, we know if we stay we are on our own. But, most people know how to prepare and know what to do during and after storms. But we stay because this is home.” And in the aftermath of a destructive storm, Irene says, “The only way you get through it is community.”

Despite development, tourism, and changing ways of life, the heart of Hatteras Island has remained intact: a community of neighbors helping neighbors.

ONE GREAT STORM

Ernie Foster thinks that there’s one great storm in every Banker’s life. For Hatteras village, that storm was Isabel.

She was deceptive. Reaching official hurricane status on September 7, 2003, off the coast of Barbuda, Isabel spent the next 10 days moving northwest and vacillating between a Category 4 and 5 hurricane until it made landfall. A NOAA hurricane aircraft recorded an instantaneous wind speed of 233 mph, the strongest ever recorded in an Atlantic hurricane. On September 18, Isabel, having been downgraded to a Category 2 storm (80 to 110 mph wind speeds) two days before, made landfall south of Cape Hatteras, between Ocracoke Inlet and Cape Lookout, bringing with it a Category 5 ocean surge.

That day, a wall of ocean spilled across the island and cut a 2,000-foot-wide inlet on the north end of the Village. “For those of us who choose to stay,” Ernie explains, “There’s a resignation that stuff happens. But, what I saw happening [during Isabel] was so profound, I was in a state of shock.”

Physically removed from the outside world by the newly cut inlet, Hatteras village was severely damaged beyond any measure of the current generation’s memory. The water surge removed, relocated, or splintered most everything in its wake.

Mary Ellon compares her home to that of a war zone. “There was a side of a house wrapped around that tree with the blinds still in it,” she says. “There were propane tanks all over the place. There were ice chests from Dolphin Realty back here racked up in our trees. Tractor-trailers stuck in the middle of the highway. It was really unbelievable.”

“Cars were turned sideways,” Todd adds, “stuck up under a house between pilings, with big fish in them. We had a 7-foot hole in between our house where the water was coming through and the tide was so strong there were red drum in it. Trailers and houses were dropped in sinkholes or washed half a mile out in the sound. Caskets floated up out of graves.”

Beth Midgett, Reservations and Sales Manager at Midgett Realty, recalls “Fifty-six structures of the 170 managed [by Midgett Realty] were condemned… It took until the first or second week of June to be back online and fully ready for the season.”

Stories of destruction, peril, tragedy abound. Jeff Oden, owner of the Seagull Motel, understands this all too well. When Isabel hit, his daughter, Marci, was managing the mom-and-pop 45-room motel at the north end of the village. She’d wanted to stay and look after things during the storm. When imminent destruction became apparent, Jeff frantically made his way to his daughter. After numerous attempts, Jeff arrived at the hotel clinging his surfboard for support. The building he had instructed her to move into was gone.

Wading into the remaining structures past hissing propane tanks and fuel-filled water, he found Marci, “absolutely hysterical,” in the attic with her pug. He recalls, solemnly, “I had no idea she was going to be there. She was lucky… That day had a profound and lasting impact on her.” Today, the lot where the Seagull Motel stands is mostly open. Isabel washed away two of three buildings on the property. Only 15 rooms remain.

It took two months for electricity and water to be restored and for the road to be repaired. Isabel was the most destructive storm North Carolina has seen in the last two decades, costing the state nearly $450 million, $110 million of which was sustained in Hatteras village across a population of 634.

UNITING THE COMMUNITY

In a place like Hatteras the profound effect of the weather is evident. Perhaps, no more evident than in the aftermath of Hurricane Isabel. However, what had the power to physically rip apart a community, oddly united and restored it.

Beth Midgett recalls, “Weather, in a very strange way, makes for community. Sometimes in a small community things feel divisive, but never over a storm. You may be miffed with someone over something superficial, and then a storm happens, and everyone has everyone’s back.”

Isabel came at an interesting time for Hatteras village. Pervasive conflict over development and building regulations left competing sides battered and bruised. Isabel reunited factions. It was the great equalizer: people helped each other; people looked out for one another; people gave and received.

“It was truly the best of times and the worst of times,” Ernie explained. “The worst of times was the physical damage and the monetary damage: loss of jobs, loss of property above and beyond insurance. On the other hand, we had a communal experience and it literally brought out the best in everyone who was here.

Y o u saw good, good, and more good.”

Support from northern villages poured in. Volunteers and supplies arrived in droves. Restaurants sent down elaborate, catered meals. Dirty laundry from the village was loaded onto boats and sent to a neighboring community where it was cared for by church groups and returned the next day. A bicycle shop in Nags Head delivered bikes for villagers to use as transportation.

Vi llagers ate together communally. They gathered outside emergency showers in the evening for a few minutes of respite. They prioritized their own needs and repairs behind the elderly and infirm. They helped each other rebuild their lives physically and emotionally.

The village had become such a tight-knit, supportive community during the two months in which it was isolated from the rest of the world that leaving the island, only temporarily, was unsettling for locals. When Ernie left the village three days after the storm to take an aerial tour of the destruction, he realized, “I had this tremendous urge to get back here [Hatteras village] — to leave normalcy and get back to chaos. The notion that I just needed to be here, rather than be some place that was normal, was a clear indicator to me that I was dealing with some emotional forces that were pretty strong.”

As Highway 12 prepared to reopen in November, two months after Isabel, a different sense of loss emerged. This time, the loss of privacy and intimacy. A new floodgate was bulging: debris and personal effects were still piled high in yards; restaurants, motels and shops had been destroyed; those that hadn’t, stood damaged, yet to be repaired. And now, there was an audience. The village wasn’t emotionally or infrastructurally ready to host visitors — it wouldn’t be until the following spring.

Mary Ellon recalls, “It was a very vulnerable spot because the community had been through a huge ordeal that made us really close. We were really vulnerable. When they were ready to reopen that road, we thought, ‘We kind of like it just like this.’”

Hurricane Isabel left an indelible impact on the spirit of the Hatteras village. Every year since, the community has gathered for a Day at the Docks event in September where locals and visitors celebrate the heritage of the island and honor the lives of those lost at sea at the day’s keynote event: the blessing of the commercial and charter boat fleet. It is clear at Day of the Docks that Isabel remains a fresh part of the collective identity of the village. This year a minister and U.S. Coast Guard bagpipe player, who helped rebuild the community after Isabel, blessed the fleet.

“The Outer Banks have never been for the faint of heart or the dry of feet,” Tom Carlson writes. The unencumbered spirit of Hatteras Island and its abundant natural beauty come at the sacrifice of willingly submitting to the weather. In a place where life and livelihoods are shaped by the forces of nature and weather, survival depends on sheer grit, determination, and the support of community.

Carlson continues, “Early on, especially, it seems, the inhabitants of the Outer Banks didn’t merely adapt to their environment; they became indistinguishable from it – its moody, impetuous weather, its restless land, its willfulness, its stubborn insistence on beating the odds.”

That was certainly the case for my great-grandfather, Baxter, and the U.S. Lifesaving Service crews across the island, who faced perilous seas with bravery, courage, and fearlessness. And it’s true today. It’s in the stories and faces of locals like Ernie Foster, Todd Ballance and Jeff Oden. It’s written in sand and cast in the sky. It seeps from the waters that sustain the villages. It must be in the hearts of the people who choose to live on a sandbar on the edge of the world.

Just as the wind brings destruction, it ushers in, on a calm southwest wind, that transparent, blue-green ocean glow and saturates the sky before dusk, mystically binding you to the place.

(Baxter Miller is a co-founder of Bit + Grain, a new website dedicated to telling the story of North Carolina and its people, places, and culture. She was raised on front porch tales of shipwrecks, pirates and lifesaving heroes that her father relayed through a dimly lit hurricane lantern on Hatteras Island. She loves the Old North State mostly for the folks who live here, because it’s the people who bring a good story to life. To read more Bit + Grain, go to http://www.bitandgrain.com/.)