Deeper Dive into the World of NC’s Sea Jellies

In this second of a two-part look at sea jellies and their relatives found in North Carolina waters, we’ll examine the world of siphonophores and ctenophores.

Siphonophores are hydrozoans and include the threateningly named and potentially dangerous Portuguese man-of-war.

“The Portuguese man-of-war is actually a colony of zooids (small animals) that work together for survival,” said North Carolina Aquarium Education Curator Dia Hitt. “This is called a siphonophore. The tentacles have venom-filled structures called nematocysts on them that they use to capture prey. Unfortunately, these structures can also cause a powerful sting in people. They are not considered jellyfish since they are not one animal but many. They don’t have a propulsion system; instead, they are at the mercy of the wind and the currents, which is why some years we see them and other seasons we don’t.”

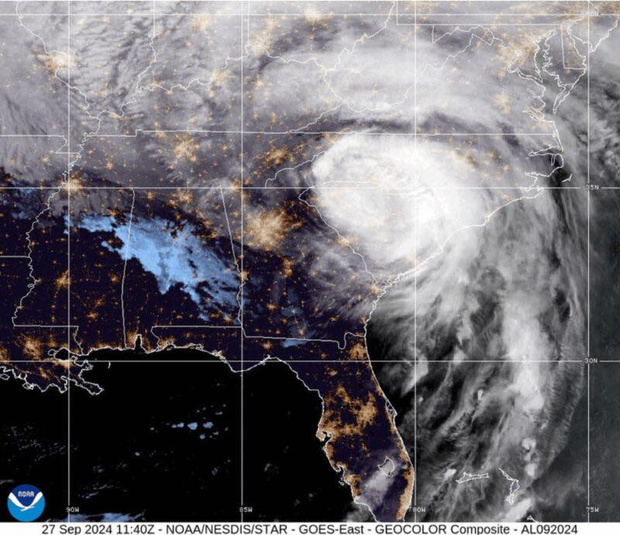

Hitt said the number of Portuguese men-of-war seen during a season depends on the storm tracks and the winds and waves, or swells, they generate.

“We can go without any all season or we may get several episodes,” said Karen Duggan, interpretive park ranger at Cape Lookout National Seashore. “The number coming ashore will vary and it is often really hard to estimate as we have four individual islands — two are about 20 miles in length, one is about 9 miles in length and the last is only a mile or two.”

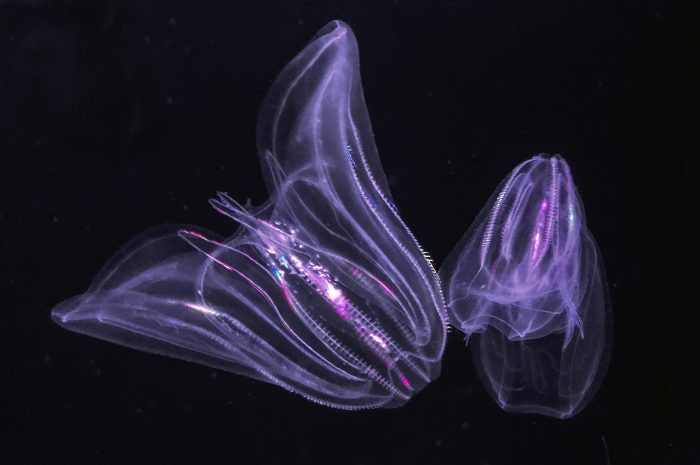

Comb jellies

The pink comb jelly is a member of a group of gelatinous zooplankton called ctenophores, which do not swim like true jellyfish. They do not contract and relax the bell, or top of the jelly, for propulsion. Rather, ctenophores rely on eight rows of hair-like structures called cilia that move in a wavelike pattern and slowly propel this animal through the water.

The pink comb jelly is about the size of a golf ball, lacks lobes like a true jellyfish and, as the name implies, tends to be pinkish and sometimes brownish in color.

This species is longer than it is wider in shape, sealed on the top and open at the bottom. Its rows of cilia give off a rainbow spectrum of color when struck by a light source, such as a dive light or camera flash.

During spring and summer months, comb jellies, like moon jellyfish, congregate in huge numbers in coastal waters. I have had to gently push several out of the way to get a photo of a single animal.

Comb jellies’ range in the Atlantic is from the Arctic to the Mediterranean Sea in the east, and from Maine to Florida in the Western Atlantic.

Comb jellies are predators that feed in large gatherings, or swarms. Its cilia not only propel but also function by creating a feeding current that delivers fish eggs, fry, copepods and other tiny zooplankton to be eaten.

Another interesting ctenophore is the sea gooseberry. These are much smaller that their larger cousin the pink comb jelly and have two tentacles that hang down beyond the bottom of the animal.

The clear, transparent body has a slightly oval shape about 1 inch in diameter. Like all comb jellies, the sea gooseberry has eight rows of cilia.

Though small, this voracious predator with its tentacles that can be up to 20 inches long, feeds on eggs, larvae, small mollusks, arthropods and almost anything else that it can catch.

The tentacles can be withdrawn inside the body and have sticky filaments all over that almost guarantees success in capturing prey. Once caught in those tentacles, it’s almost impossible for any prey to escape.

True jellies and comb jellies also differ in that the comb jellies have no venom to paralyze their prey.

Sea gooseberries are considered intersex, meaning they have both male and female organs. Eggs and sperm are released into the water at the same time when fertilization takes place. They can live in depths ranging from just under the surface down to as much as 656 feet.

Sea walnuts

Quite common in North Carolina, the population of this jelly soars seasonally, usually during summer months, but they are usually around the North Carolina coast year-round.

Sea walnuts are shaped like their name implies, like the shell of a walnut. As adults, they do not have tentacles, and can grow to several inches in length. Sea walnuts are yet another species of comb jelly and have the same “light show” qualities and method of propulsion.

Sea walnuts are typically transparent or white. They can produce light when disturbed and can be seen flashing brightly in the waves of passing boats at night, similar to waving a hand through the water and seeing green bioluminescence.

This animal is also found in almost every ocean on Earth.

Many-ribbed jellies

The many-ribbed jelly is saucer-shaped with a well-developed bell. The top of the bell is called the velum and is a membrane that points inward from the margin of the bell. These jellies can be identified by the 80 or more narrow, unbranched radial canals, or rows, that extend all the way to the margin of the bell.

According to Walla Walla University, the slender gonads run along most of the length of the radial canals and do not hang down. Gonads are bluish in males, rosy in females. They have one to several unbranched tentacles for each radial canal. All tentacles hang from the margin of the bell. The tentacles are in a single row around the margin of the bell, can be extended long or held very tightly inside the bell. These tentacles are irregular in size.

The bell can have a diameter of more than 3 inches with ruffled edges and is usually transparent. They range from Texas to Maine and east to the Mediterranean Sea. They are typically seen nearshore.

Many-ribbed jellies feed mainly on gelatinous plankton such as other hydromedusae, ctenophores, polychaetes and appendicularians. It may occasionally be cannibalistic, and also eat larval fish such as Atlantic herring.

This species is also bioluminescent and may flash brightly when disturbed.

Blue buttons

The blue button is not really a jelly at all. They are actually a hydroid and, like the Portuguese men-of-war, are colonial animals made up of individual zooids, each specialized for a different purpose such as eating, reproduction or defense.

This species can be quite small, measuring only about an inch in diameter, but can grow to be as large as several inches across. They are made up of a hard golden-brown, gas-filled float in the center surrounded by blue, purple or yellow hydroids, which look like tentacles. The tentacles have stinging cells called nematocysts. Blue button jellies are found in warm waters off Europe, in the Gulf of Mexico, Mediterranean Sea, New Zealand and in southern U.S. waters, including North Carolina.

These hydroids live on the ocean surface and are frequently blown to shore by the thousands. Blue buttons eat plankton and other small marine life. They rely on prevailing currents and winds to move around the ocean and are often prey for sea slugs and sea snails.

By-the-wind sailors

Finally, and again, not really a jelly, the by-the-wind sailor is a hydroid polyp that floats at the surface of the Atlantic Ocean for most of its life. It’s only ever completely submerged during its larval stage.

This species begins life in the middle of the ocean, is brought in closer to shore by the wind, and is typically blown up on a beach where it dies and then disintegrates.

This jelly is most common on the high seas, in the warmer regions of the Southern and Northern hemispheres.

The by-the-wind sailor is sometimes mistaken as a smaller version of the larger Portuguese man-of-war with its cellophane-like floats and erect triangular sail. The sail is blue to purple in color with a flat oval, transparent balloon, or float. The angle of the sail is such that the by-the-wind sailor can take best advantage of the wind. This species may have sails oriented from left to right or right to left.

In late spring and early summer, they arrive on the North Carolina beaches.

The joy of diving

Jellyfish are the coolest critters I have ever had the opportunity to dive with and photograph.

They are another reason that we call scuba diving a sport that takes you into “inner space.” Swimming and breathing with fish and invertebrates is my way of feeling like an astronaut, but instead of being in outer space, I’m underwater!