Future Seasons’ Oysters Need Recycled Shells

It’s the time of year when North Carolinians feast on that culinary delicacy, the humble oyster. But dining on oysters needn’t, and shouldn’t, be the end of the story. After the oyster’s gone, there’s the oyster shell, and advocates say it should be returned to the water where it can provide a safe harbor for future oysters.

That’s where the North Carolina Coastal Federation’s Oyster Shell Recycling Program can help. The federation is publisher of Coastal Review Online.

“The North Carolina Coastal Federation is working with volunteers, local governments and businesses to rebuild the oyster shell recycling effort in North Carolina,” said Ted Wilgis, the federation’s coastal education coordinator in Wrightsville Beach. “We know oyster shells are important and that people want to be a part of the recycling effort.”

Oysters’ Vital Role in Our Ecosystem

Oysters could be called the powerhouses of the sea. These small organisms provide food, filtration and fish habitat, said Leslie Vegas, a coastal specialist with the federation’s Wanchese office.

Oyster Shell Drop-Off Sites

All three Coastal Federation offices:

Brunswick County

New Hanover County/Wilmington:

- Seawater Lane, Wrightsville Beach.

- Bridge Barrier Road, Carolina Beach State Park.

- Entrance to Airlie Gardens.

- Trails End Boat Ramp & Park.

- New Hanover County Landfill.

Onslow County:

- Morris Landing in Holly Ridge.

- Onslow County Landfill.

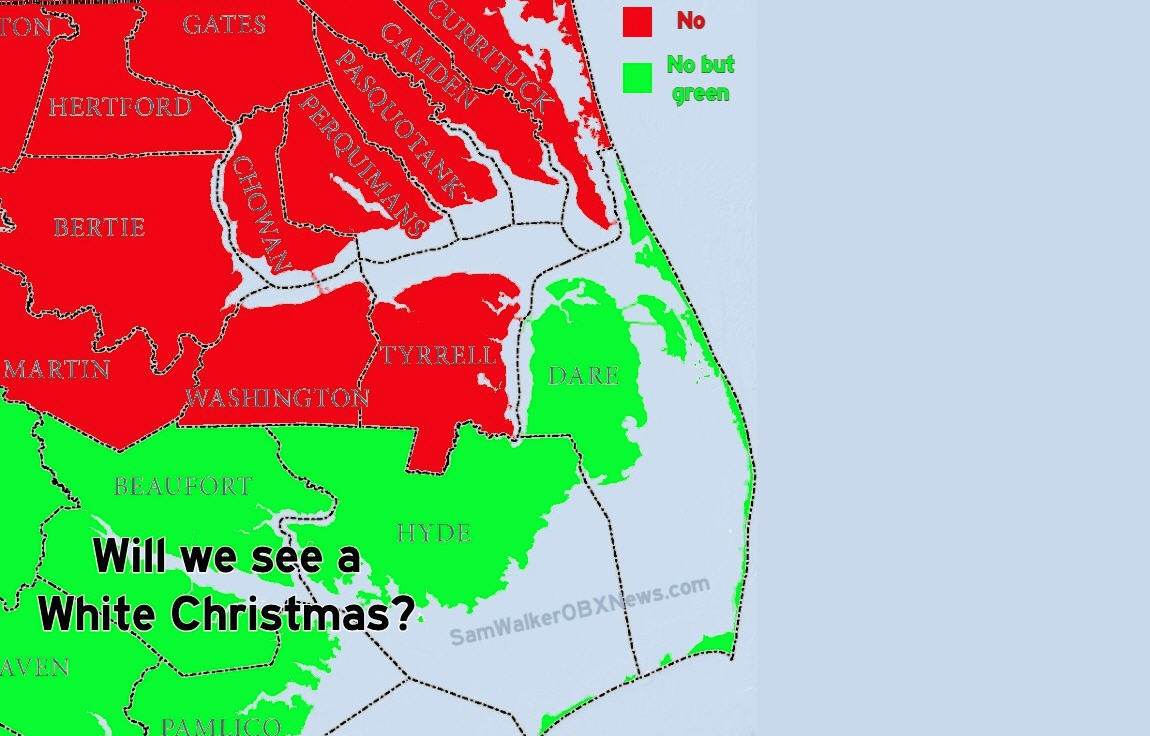

Dare County:

- Kill Devil Hills Recycling Center.

- The Nature Conservancy at Nags Head Woods.

- Wanchese Marine Industrial Park.

Orange County

First, oysters are central to the food chain. They are a food source for numerous animals including crabs, sting rays, skates and birds. And oysters, in turn, eat phytoplankton, the small bits of algae in the water. Second, oysters are one of nature’s most efficient and hardworking filtering systems: Just one oyster cleans 30 to 50 gallons of water per day. Third, oyster reefs are not only home to 75% of the fish and shellfish we eat, they also serve as spawning sites and nurseries for several species, said Wilgis. Finally, oyster reefs help stabilize the shoreline by buffering it from erosion.

Because they are necessary for both habitat restoration and ensuring a healthy oyster population, oyster shells may be as important as the oysters themselves.

“Oyster shells are essential to having a sustainable or resilient oyster population,” said Wilgis. “Oysters need coastal reefs, and coastal reefs need oyster shells.”

Though coastal reefs are often made of cultch material, such as crushed concrete, limestone or granite, this base must also include oyster shells, and the more the better. Oyster shells provide a hard surface with lots of nooks and crannies that oyster larvae prefer, because they can easily latch onto it and then grow their own shells.

“They (oyster larvae) prefer to land on themselves,” said Vegas. “If they don’t find a place to land in the water, they’ll die off.”

Oyster shells are deemed so valuable that in 2010 the North Carolina General Assembly made it illegal to dispose of them in landfills.

A Declining Resource

The state’s coastal regions are in dire need of oyster shells. Years of overharvesting has interfered with the oyster reproduction cycle, so much so that the state is at 15% of its historical harvesting rate, according to Vegas.

Climate change, too, has contributed to the decline of the oyster population. Changes in the ocean’s acidity and salinity as well as extreme weather patterns can make it difficult for oysters to spawn, make them less healthy and thus vulnerable to predators, or cause them to die. As an example, the influx of fresh water into the Cape Fear River during Hurricane Florence killed many of the river’s oysters.

“The Cape Fear River went from a brackish mixture of fresh and saltwater to a freshwater river, even almost to the mouth of ocean, for three weeks,” Wilgis said. “Oysters can’t tolerate that amount of fresh water, so most of the oysters in the Cape Fear River died.”

With the declining oyster population, demand for their shells is high. North Carolina and other coastal states compete for the same shells. In addition, businesses such as chicken feed manufacturers also vie for the shells. As a result, oyster shells are at a premium. The cost of a bushel of shells has risen from 25 cents in 1998 to the current price range of $3.50 to $7 a bushel, Wilgis said.

Oyster shell recycling fills the gap between the number of shells organizations can buy to build oyster reefs and how many are needed.

“Shell recycling is a way to get every last bit of shell that we can while trying to get it at the same cost as the other materials out there,” Wilgis said.

Rebuilding the Recycling Program

The Coastal Federation is working to rebuild the state’s oyster shell recycling program, which was phased out last year when it lost the last of its funding. In southeastern coastal areas of the state, the organization is partnering with counties and nonprofits to provide shell dropoff sites. In addition, New Hanover and Orange counties are hauling shells to the stockpile sites at no charge.

“The program is slowly getting off the ground, but we’re excited about the opportunities and that local governments are interested,” said Wilgis. “The local municipalities are excited because it keeps valuable shells out of the landfill. They also get the benefit of recycling and getting the shell back into the water.”

Wilgis said he plans to expand the program in the future. In addition to increasing the number of shell-collection sites, he wants to involve more businesses in the program. Wilgis said he is looking to convince restaurants, which are often big contributors to oyster shell recycling, to recycle their shells. Another goal is getting private waste hauling and recycling companies to take shells to stockpile locations at no charge. Through these efforts, Wilgis said he hopes to increase the number of shells recycled in the area from last year’s 1,000 bushels to 30,000 bushels.

“That’ll involve a lot of partnerships and getting the private companies and restaurants involved,” he said.

The federation’s northeast region is piloting a Restaurant to Reef recycling program. Volunteers, with backup help from federation staff, collect shells from participating restaurants and deliver them to public drop-off sites. The federation also, on a case-by-case basis, helps organizations holding large events coordinate the transport of their shells to a drop-off site, said Vegas. A third prong of the recycling effort is educational programming provided by the federation.

Like Wilgis, Vegas is working to grow the recycling program by securing more drop-off locations, adding more restaurants to the program and engaging more volunteers. Vegas said she also wants to secure funding for educational materials, outreach and supplies.

Volunteers are needed for both programs. Their assistance can be as extensive as volunteering regularly or by simply bringing a bag of five or six shells to drop off points.

“People get very excited about oyster shell recycling,” Wilgis said. “They feel a connection, that they can do something to help, whether it’s just a few shells or a lot of shells.”

The federation urges the public to enjoy oysters and then to take the next step: participate in oyster shell recycling. Volunteer or ask restaurants to participate in the oyster shell recycling programs and recycle oyster shells from family’s and friend’s dinners and oyster roasts.