Is the Ocracoke Brogue on the endangered list?

By Maggie Miles From OuterBanksVoice.com

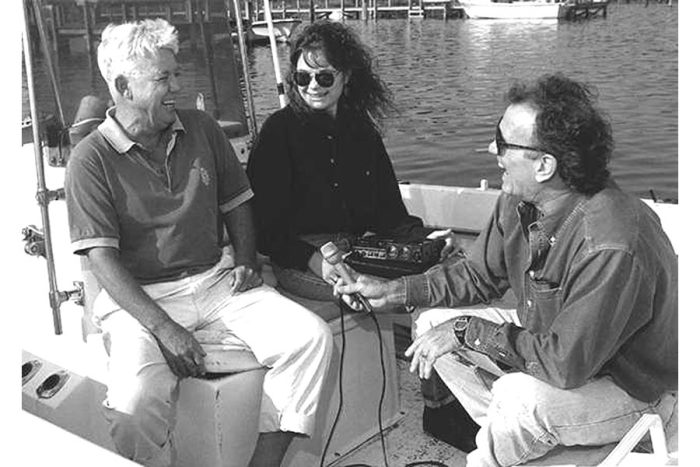

Recent research from the Linguistics Department at North Carolina State University has found that southern dialects of North Carolina are disappearing at a rapid rate. The primary contributing factor to this, according to Walt Wolfram, American sociolinguist and William C. Friday Distinguished University Professor at NC State who leads this research, is the influx of out of state residents moving to North Carolina.

One of the southern dialects that is becoming increasingly rare is found right here on the Outer Banks. According to Wolfram, Ocracoke Brogue, or the “Hoi Toider” accent, as it is commonly known, is derived mainly from early settlers of Ocracoke who came to the island in the 1700s from Jamestown, which was the first permanent English settlement, and Philadelphia, which consisted of mostly Irish settlers.

“So what’s really interesting about Ocracoke is that the Ocracoke Brogue, along with the dialects on the other islands like Smith Island [Maryland], and Tangier Island [Virginia], is that they are the only dialects in America that don’t sound American,” says Wolfram.

As part of their research project, Wolfram’s team once had a prominent British dialectologist, Peter Trudgill, visit the Outer Banks. He took back some recorded samples of Outer Banks speech and played them to a group of native speakers of British English. “And not one person said they were from the Americas. They all thought they were from England somewhere,” he recalled. “And that makes it unique.”

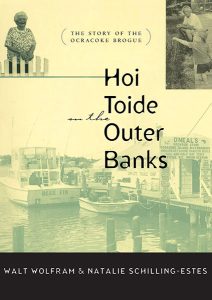

Wolfram and his team of linguists at NC State have been studying Ocracoke Brogue for more than 30 years, conducting and recording more than 130 interviews with local residents and teaching classes on the dialect at NC State. Wolfram and his team have published 30 articles and numerous books including Hoi Toide on the Outer Banks: The Story of the Ocracoke Brogue (1997 UNC Press) and a forthcoming book that will be out this spring titled Language and Life on the Outer Banks: The Ocracoke Brogue. It includes QR codes that give readers the ability to hear audio and watch videos of the brogue speakers quoted in the article.

In addition to the Elizabethan accent with its distinct vowel pronunciations, such as “soid” instead of “side,” “saind” instead of “sound” and “far” instead of “fire,” Ocracoke Islanders have their own distinct vocabulary. “O’cocker” is a person born and raised on Ocracoke who can trace their family history there back a couple of centuries. According to Wolfram’s talks with locals, 300 to 350 people now on Ocracoke are “O’cockers” and he estimates that around 100 of them can speak the Brogue, with many of them being in the older population.

In addition to the Elizabethan accent with its distinct vowel pronunciations, such as “soid” instead of “side,” “saind” instead of “sound” and “far” instead of “fire,” Ocracoke Islanders have their own distinct vocabulary. “O’cocker” is a person born and raised on Ocracoke who can trace their family history there back a couple of centuries. According to Wolfram’s talks with locals, 300 to 350 people now on Ocracoke are “O’cockers” and he estimates that around 100 of them can speak the Brogue, with many of them being in the older population.

“I think the thing that is really sort of interesting is that the whole region used to be identified by their speech, and they were called “The Hoi Toiders,” he says, referring to the relatively small group who still use the dialect. “But of course, things change over time, and that’s how things are.”

Then you have the “dingbatters” which is someone who isn’t originally from the island. That term, Wolfram says, originated from the show All in the Family. (“Dingbat” was a term that the irascible Archie Bunker used on the show to refer to his long-suffering wife Edith.)

Wolfram credits the isolation of the island for the preservation of the distinct dialect. But he says that began to change in the mid-twentieth century when it underwent an economic and social transformation with the development of roads and ferry services that made it easier for the outside world to travel to the island. That ushered in a busy tourism economy, with 4,000 to 8,000 “dingbatters” on the island on a summer day.

According to Wolfram’s research, this became even more significant when Ocracoke became recognized in national media as the best beach in the US about 15 years ago. It has since been on numerous lists across news and travel sites and publications.

In addition to the interactions of locals with tourists, Wolfram cites other factors in the fading of the dialect, including an increase in locals marrying outsiders and younger locals moving away to go to college and find jobs off the island.

One interesting thing the researcher pointed to was a gender divide. Among the older generations, Wolfram and his team found that men and women used the brogue relatively equally. But among younger generations, the percentage of women using it has declined, because as Wolfram explains, women spend more time dealing with the tourists.

With the erosion of a distinctive dialogue with such strong cultural significance and history, the question is how it will affect the identity of the island. After his conversations with Ocracoke residents, Wolfram says the most important factor in their identity is their generational roots on the island.

In a quote from Wolfram’s forthcoming book, Candy Gaskill, a local O’cocker known for helping preserve the history of Ocracoke says: “It’s not the Brogue that’s home, it’s the people and the warmth, you know, the love and the community, the togetherness…I don’t really think it’s the Brogue or the dialect. I think it’s more the people that makes it.”

American accents started disappearing when network TV demanded neutral accented voices, and people learned to speak from watching TV more than listening to family. Almost no one under 40 has any kind of distinguishing accent.