Island History: The Unfathomable Tragedy and Mystery of the Wreck of the Robert H. Stevenson

The schooner Robert H. Stevenson has almost been lost to the historic records. She was only three years old when she disappeared forever on the infamous Diamond Shoals. Very little makes sense about the wreck and ensuing non-rescue, and there remains a hugely significant amount of a mystery surrounding the whole affair.

The Services

The Services

From 1871 until 1915, the United States Life-Saving Service (USLSS), a land-based water rescue service, had the singular mission of saving lives in peril from the sea. Its sister maritime organization, the United States Revenue Cutter Service, (born “Revenue Marine”), also had a singular mission: water-based law enforcement. When these two services merged in 1915, the name was changed to the United States Coast Guard (USCG).

Each U.S. maritime rescue Service – the U.S Life-Saving Service and the U.S. Coast Guard – has had an incredible record of success. In the 44-year history of the Life-Saving Service, America’s Forgotten Heroes nationwide responded to over 178,000 lives in peril from the seas, of which they saved over 177,000. Their own loss of life during rescues – with cork lifejackets as their only safety equipment – was less than one percent. Today’s Coast Guard continues this amazing rate of success, usually with little publicity.

Each Surfman then, and each Coastie since, lives to serve, to protect and – mostly – to save. The few times that they were unable to save a life were the most dreadful, heart-felt losses for them. The saddest of all sad situations, however, going beyond a loss, was simply not even being able to attempt a rescue. Many circumstances accounted for these rare events. The story about to be told is one of these instances.

Early 1900s

If Hollywood would have made a movie of this event, during this time, it would have produced yet another extremely exaggerated story that no one would have believed. But this was real.

There is scant public reference to this dramatic event. The account in the Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1906 has but a single word beside the schooner’s name: “Stranded.” There was no article in David Stick’s famous classic book, Graveyard of the Atlantic; Shipwrecks of the North Carolina Coast. There were only two small newspaper articles. One a nine-inch column in the New York Times five days later, and a four-inch column in The Boston Daily Globe thirteen days later, albeit on the front page.

Yet there were notable names involved in this story – the cities of Boston and Savannah, the country of Germany, a ship named Europa, and the most iconic name, the Diamond Shoals of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Even stranger, and to repeat, there is a hugely significant amount of a mystery surrounding the whole affair.

The Ship

Little is found about this vessel. The Robert H. Stevenson was a 1,290-ton, four-masted schooner, built in Bath, Maine in 1902, according to the Steamboat Inspection Service. Her homeport was Boston, Massachusetts. Thus, she was only three-years old when she met her demise. Her payload was not specified, but being a large cargo vessel coming from Cuba in 1906, a good guess would be sugar or tobacco.

Newspaper Articles

The first report came from the New York Times. It had a dateline of Savannah, Wednesday, January 17, but was published in New York on the 18th. The headlines read:

“ADRIFT ON GANGPLANK.

Castaway Saved. After Three Days –

Twelve May Have Perished.”

Details were sketchy at best, all based entirely on the accounts given by Karl Sumner, a sailor on the schooner Robert H. Stevenson, and the sole survivor of the thirteen aboard.

According to Sumner, the schooner was bound from Havana to Philadelphia. On Saturday, January 13 at 3 a.m. during a nor’easter, the Stevenson went hard aground on the treacherous Diamond Shoals off Cape Hatteras. Sumner then described the “falling dominoes” of the fate of the other twelve persons aboard.

Captain Higbee ordered a lifeboat to be lowered. First Mate Lewis and two seamen entered it when the violent surf smashed the lifeboat into the schooner, exploding it to bits and immediately drowning the three of them as the rest on ship’s personnel witnessed the horror.

A second but smaller ship’s boat was successfully lowered and filled with the captain’s wife, two of his female relatives, an African American servant, and the reluctant Captain Higbee himself. Sumner saw all of this, but never saw them again, nor did anyone else. Eight persons lost so far, leaving five left, including Sumner. Three of those decided to leave “as best as they could,” and two of those quickly assembled a make-shift raft and launched into the boiling surf. The fourth decided to remain on the schooner, which by then was soon going to pieces, as can happen to a wooden ship bashed with the enormous power of gigantic, rushing waves.

As a last resort, with the vessel coming apart all around him, (and acting mostly out of desperation and panic), Sumner found a loose gangplank. It was three-feet wide and around twenty-feet long, and he threw it in the ocean. He jumped overboard, crawled up on the gangplank, and somehow managed to tie himself to it with a stray piece of rope.

“Ship after ship passed,” the Times article continued, “but none within distance to discover him until the Europa approached more closely and saw the coat he waved. He was picked up more dead than alive.” If you need a visual, this episode feels a lot like the scene with Tom Hanks in the 2000 feature film Castaways, (with “Wilson”), as the gigantic steamer drifted silently by. Picture that.

The Boston Daily Globe

The Boston Daily Globe

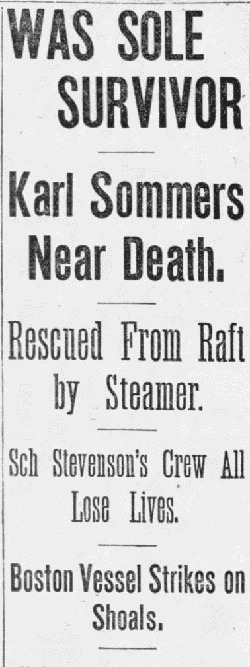

Published on Friday, January 26, 1906, (thirteen days after the incident), and being in the schooner’s homeport, the Globe was able to afford greater detail. These were her actual headlines that day:

We now learn the names of many of the other twelve: Captain Jonas E. Higbee, his wife of Northport, Long Island, Miss Wicks, a neighbor of the captain’s family at Northport, “a colored stewardess,” first mate William Lewis of Everett, steward Frank Carroll of East Boston and a sailor named Olaf Olsen. Sommers did not know the other names – the second mate, the engineer, and three of the sailors.

The Boston Daily Globe reports that Sommers “was adrift on a 20-foot plank from the morning of Jan 13 until the evening of the 15th, lashed by a piece of rope to prevent his being washed overboard, and during that time he was fighting off sharks which hovered about the plank waiting to devour him.”

A Necessary Tangent

“Yellow Journalism” is a term for the use of lurid features and sensationalized news in newspaper publishing to attract readers and increase circulation. The phrase was coined in the 1890s to describe the tactics employed in the furious competition between two New York City newspapers, the World, owned by Joseph Pulitzer and the Journal, owned by Randolph Hearst. He brought in some of his staff from San Francisco and hired some away from Pulitzer’s paper, including Richard F. Outcault, a cartoonist who had drawn an immensely popular comic picture series, “The Yellow Kid,” for the Sunday World. After Outcault’s defection, the comic was drawn for the World by George B. Luks, and the two rival picture series excited so much attention that the competition between the two newspapers came to be described as “yellow journalism.” 2

So, was the description about the sharks accurate? Probably not. Note also the different spelling of Sommers. This was common at the time to have conflicting “facts” in early newspaper accounts.

Continuing the Newspaper Accounts

Here, the Globe report has more details to add to the Times account. In the rescue of Sommers by the German steamship Europa, the report says, “His tongue was swollen and protruded from his mouth, and his limbs were so weak that he was unable to stand. He was tenderly lifted into the lifeboat sent from Europa and taken on board where he was put between blankets and carefully nursed until the vessel reached Savannah.” Sommers remained in the Savannah hospital for another four days, until January 19, when he had recovered enough to return home back north. While he was still in the hospital in Savannah, the New York Times was able to interview him for their story.

Scorecard

It can be a little confusing here who was going where and when:

- Schooner Robert A. Stevenson, homeport of Boston, going from Havana to Philadelphia, wrecked on Cape Hatteras January 13, 1906.

- Sailor Karl Sommers drifts on a gangplank on January 13, 14 and 15.

- German steamship Europa, leaving Philadelphia bound for Savannah, spots and picks up Sommers on January 15.

- Europa takes two more days to reach her destination, arriving in Savannah on January 17 with Sommers taken to the hospital there. New York Times posts an article

- Sommers recovers and returns to Boston, January 19. Boston Globe publishes account January 26.

The Unknown Tragedy

The initial reaction to hearing the basics of this saga for the first time is, “why didn’t the U.S. Life-Saving Stations in the area respond?” There were at least six in that vicinity: Big Kinnakeet, Cape Hatteras, Creeds Hill, Durants, Hatteras Inlet, and even Ocracoke, all being only miles apart from each other. The most obvious answer to that good question, after examining all of what was known as well as what was not known at the time, is – they never knew about it. The stations did not see anything, nor did they hear anything. To find all this out days after the tragedy would be the saddest of sad situations for these souls dedicated to saving lives from the peril of the seas at their own utmost risk. Why this did NOT happen is a mystery that makes no sense.

The Makings of a Mystery

What is known:

- The schooner Robert H. Stevenson wrecked at 3:00 a.m. on January 13. That was in the middle of a stormy, pitch-black, cold night.

- It wrecked on the Diamond Shoals off Cape Hatteras. The farthest reaches of those shoals go out for twenty miles.

- The distance to the horizon for a six-foot person at sea level is three miles.

- The distance to the horizon for a six-foot surfman on watch from the thirty-foot high floor of the station’s watch tower is still only 6.7 miles.

- So, if this wreck was seven miles or more off the coast, it would have been impossible for any watchmen to see it, even in daylight on a clear day.

- All U.S. Life-Saving Stations in this 6th District station logs are kept on file at the National Archives, Atlanta location. A search of those logs for all nearby stations from January 12 to January 19 of 1906 reveal no trace of any shipwreck or distress signals or even shipwreck flotsam. No flares were sighted, no International Signal Code Flags shown, no rockets fired, no wireless messages of distress – no CQD, no SOS.

- We also know this was a very large schooner with probably a very valuable cargo.

- We know it had come from Havana, Cuba in 1906. A revolution had just begun there.

- We know that it had an unusual contingent of people on board: not only four women – highly unusual at the time for a huge cargo vessel – but they were a tight-knit social group: the captain’s wife, his female relatives, neighbors and even a servant.

The Unknown ‘Whys’ of the Mystery

- Why did the schooner have no warning of an impending wreck?

- Why was the Captain unsure of where he was – a cardinal rule of navigation violated; especially during a storm, at night, and in one of the most notorious shipwreck locations?

- Seaman Sommers reported that after the “schooner struck with a terrific force,” it was then “pounded heavily for two hours.”

- This was plenty of time to fire distress flares and/or rockets; why did they not?

- Plenty of time to send multiple telegraph distress messages; why did they not?

- Plenty of time to come up with a much better survival plan than they used; why did they not?

The Surfmen of the United States Life-Saving Service stations around the Diamond Shoals off Cape Hatteras deeply regretted that the crew of the schooner not do even one of the above things.

In the End, the Real Tragedy

For the Lifesavers to learn of a shipwreck – after the fact – when no help could be offered, was almost more than they could handle. With all of their extensive training, commitment to their duties, with the utmost fidelity and vigilance, that outcome was heartbreaking. Yet, it will be these very circumstances that would lead to continued improvements and increases in their astounding records of success, so that others may live.

In the End, the Real Mystery

Long before the Outer Banks of North Carolina’s most famous maritime mystery, the “Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals” – the schooner Carroll A. Deering – in 1921, and before the multitude of unanswered questions for the inexplicable loss of the “unsinkable” Titanic in 1912 whose fatal telegram was received in Hatteras Village, was another Outer Banks nautical mystery on par with both of these stories. Yet, while the stories of the Deering and the Titanic are wildly famous, what happened to the Robert H. Stevenson is still virtually unheard of by the public.

So, perhaps the greatest mystery of this mystery is: Why is this incident still so unknown to this day?