One Remains Upon a Pedestal of Coast Guard History to This Day. They Happened 122 Years Ago This Month.

By James D. “Keeper James” Charlet

Two of the most daring and dramatic shipwrecks in American history occurred off of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. They were not only in the same month and year of 1899, but they were also on two consecutive days. The first incident was the mystery of one of the strangest, most bizarre, and most inexplicable shipwreck stories of all time. The second is a nearly unbelievable story of individual heroism that is still unmatched today. Both wrecks were responded to by the unheralded United States Life-Saving Service (1871 – 1915). In 1915, it merged with the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, and was renamed United States Coast Guard.

The Setting

Most Americans have never heard of the United States Life-Saving Service – regardless of their age, education, travel or worldliness. But during the Life-Saving Service’s 44-year history, nationwide, (and using no more than small, open, wooden boats and cork life belts), they responded to over 178,000 lives in peril, of which they saved over 177,000.

The date was August 1899. The most violent and destructive hurricane to ever hit the U.S. Atlantic Coast up to that point had arrived. Warnings were given through newspapers and telegrams. The hurricane had wreaked havoc in the Caribbean, destroyed thousands of homes and other buildings, killed hundreds of people, and sank an armada of an untold number of ships. After leaving the Caribbean, the storm began leveling the Florida coast and moved slowly and relentlessly north. As it crawled up the Atlantic coast, it took dead aim at Cape Hatteras.

It struck Hatteras Island on August 16. When it was over two days later, seven vessels were lost as total wrecks on the beach; six more disappeared in the tumultuous seas without a trace. This story focuses on only two of those unfortunate vessels.

First Wreck & Rescue: Schooner Aaron Reppard

The first known Hatteras Island victim of the 1899 August storm was the Aaron Reppard, a three-masted, 459-ton schooner. Carrying coal from Philadelphia to Savannah, she had a crew of seven and one very unfortunate passenger. Her voyage was a constant series of mistakes from the very beginning. What unfolded next is one of the strangest, most bizarre, and most inexplicable shipwreck stories of all time. First, she departed Philadelphia on Saturday, August 12, at 2:00 p.m. by being towed some 50 miles down the Delaware River. At 5:00 a.m. three days later, Aaron Reppard set sail heading south, already into the face of increasing winds. If only she had waited another few days.

By the following morning, the Reppard was fully engulfed by the ferocious hurricane. The now somewhat confused and disoriented Captain Wessel reckoned he was somewhere around Cape Henry, Virginia; his next big mistake. He was actually much farther south, off the Outer Banks. Earlier, he could have ducked into the safety of the Chesapeake Bay.

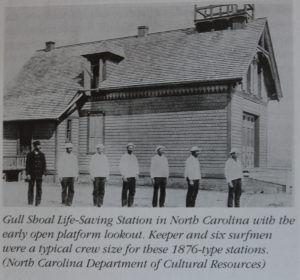

The captain’s next mistake was colossal: he decided to anchor off the coast of Hatteras Island and “ride out” the hurricane. That is when the Aaron Reppard was spotted by Surfman William Midgett on beach patrol from Gull Shoal Station. Midgett immediately knew that the schooner was in big trouble, and reported to Keeper Pugh of his Gull Shoal station upon his return. Pugh telephoned stations Chicamacomico (its northern neighbor) and Little Kinnakeet (its southern neighbor). All three stations took up positions on the beach opposite the Aaron Reppard with their survival equipment. They watched helplessly.

Although anchored, the violent wind and waves were dragging the Aaron Reppard closer to shore, closer to wrecking, and closer to certain doom. There was still time to hoist anchors and be saved from crashing onto the shore. But the captain not only didn’t do that, but instead, he did the worst thing possible – he ordered the sails raised! This naturally increased the speed at which the ship was being dragged to shore, where it hit bottom. Seeing the inevitable, all the crew of the ship and Mr. Cummings, the passenger, climbed the rigging to higher ground. Being stationary, the schooner was now taking the full brunt of each horrific wave. Each hit was so violent, that the survivors had to literally hold on to some part of the ship for dear life. The hurricane wanted to shake them off into the sea. She soon had her way.

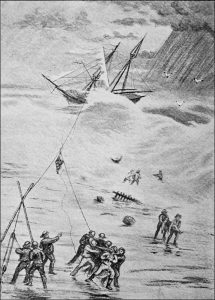

The Reppard finally was at the farthest edge of the Lyle gun range. This enabled the lifesavers to eventually establish a “zip line” with a single seat – the breeches buoy – to haul survivors to shore, but it required actions by the shipwrecked crew. They would have to retrieve and haul in a successful Lyle gun shotline. Two shots were fired and failed. The third was perfect, but the crewman could not let go of his hold to grab the line, so it did no good. Horrifying to witness by the assembled life-savers, the mariners began falling from their lofty perches. Mr. Cummings fell from the mizzenmast, caught a foot in a rope, and then became a pendulum repeatedly slamming into the mast. One by one, the crew were lost until only three remained.

Sworn to oath, yearning to save, but thwarted by the extreme violence of wind and water, the Lifesaving-Station crew members’ frustration was unbearable. They formed a new plan: Members of each station began an improvisation where one would strap on a cork life belt and tie a shotline around themselves, while two other surfmen would be their anchor onshore as they waded into the incessant, raging surf. The high winds and heavy surf carried a lethal arsenal of debris from chunks of the broken ship, even huge spars. Seventy-year-old Keeper Hooper of Station Little Kinnakeet was one of the rescuers entering the surf. Almost immediately, deadly pieces of debris struck his right leg and broke it. He continued on because he could see three sailors still alive, and that is truly what Life-Savers do. When the life-savers all finally emerged, they had those three sailors with them, still alive.

A dreadful and exhausting day…some failures but some successes. Yet all these men knew full well that it was not over yet.

Second Wreck & Rescue: Barkentine Priscilla

All the surfmen from those three Life-Saving stations returned to their stations exhausted. Nevertheless, regulations said every station required two surfmen to walk “beach patrol” in opposite directions every night, halfway to their neighboring station. Poor Rasmus Midgett, Surfman Number One at the Gull Shoal Station, drew one of the next beach patrols.

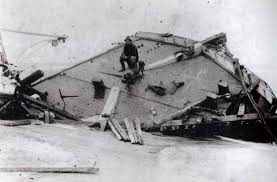

He left his Gull Shoal station at 3:00 a.m. on his personal horse. The tide was washing over the island, so he rode through the swash and rough surf. He passed one shipwreck hulk after the next from his previous experiences the day before. It was dark, loud, unpleasant, and difficult to see due to the blowing sand, rain and sea spray, and lack of light. He soon spotted more flotsam and jetsam that might be new since the day before. Arriving at the wreck, he heard the terrified screams of survivors. They were huddled in the forward half of the barkentine Priscilla, which the hurricane had torn in two, and which was nearly ashore. Still, it was the middle of the night, and the middle of a violent hurricane, and those people aboard had no idea where they were.

Rasmus was faced with an ultimate dilemma: Go back to the station to get the full crew and rescue equipment? Or go in himself now? The first choice would take far too long, he reasoned. The second was extremely dangerous for him. As a trained Surfman, Rasmus observed that the waves were very high. The relationship between the height of a wave and the distance between them is called “wave length.” The higher the waves are, the farther apart they are. So, quickly, Rasmus devised a bold and daring plan.

He called out to the ship and instructed one person to jump off when he commanded, even though he was still exhausted from the day before and had gotten little sleep. Per his plan, he would then run out between the waves, retrieve that person, and bring them safely to shore. It worked. He did that again, and again. Seven times he risked his life to save another’s, but it was not over.

By then, Rasmus had discovered three more on board, too badly injured for this plan to work. Nevertheless, he braved the gigantic waves an eighth time. After he struggled to climb aboard, he rested on the deck for a few seconds to catch his breath and to renew his strength. Then he picked up a survivor, climbed back down, timed the waves, and rushed the survivor to the beach. He did that all over again – incredibly, two more times.

By himself, Rasmus Midgett saved all 10 shipwreck survivors; in the middle of a hurricane, in the middle of the night, and after two days of previous rescues. This is undeniably an extraordinary story of extraordinary heroism.

The full stories of each of these wrecks are separate chapters in my book “Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks: Dramatic Rescues and Fantastic Wrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic.”

James D. Charlet is the author of the new book “2020 Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks: Dramatic Rescues and Fantastic Wrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic,” Globe Pequot Press.