Island History: A spotlight on stories from the Outer Banks’ Life-Saving Service

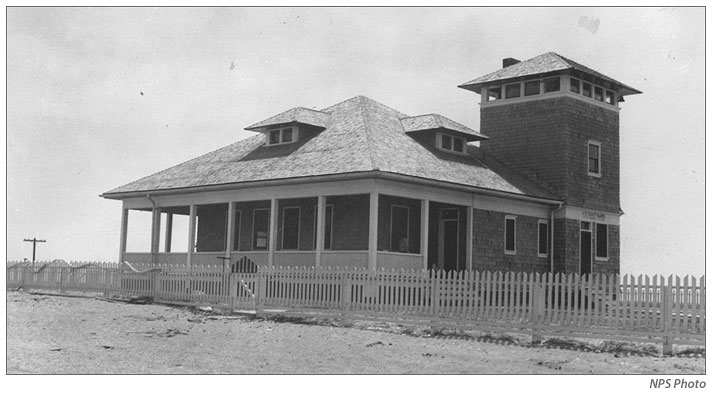

The Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station (CLSS) is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year, as one of the seven original Life-Saving Stations to be built in North Carolina in 1874.

As such, the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station and Historic Site in Rodanthe will be sharing stories about the seven 1874 Outer Banks stations in the months ahead, leading up to the official October celebration of the United States Life-Saving Stations’ 150th anniversary in the state.

The following is the next of these Life-Saving Station feature articles to honor the #LegacyofLifeSaving, written by Jen Carlson for CLSS.

Gentle Kindness – A historic rescue by the Little Kinnakeet Life-Saving Station

On February 22, 1892, a schooner was spotted through the wind and fog by a small boy who lived near the Little Kinnakeet Life-Saving Station.

He alerted John A. Midgett, and the experienced Keeper realized that while the schooner hadn’t grounded yet, the trajectory of her course indicated it wouldn’t be long.

He immediately called the sister stations of Gull Shoal and Big Kinnakeet to assist in the rescue. Within 45 minutes of the boy’s message being delivered, all three stations were on site where she had beached about two miles south of the Little Kinnakeet station. The breeches buoy was quickly set up, and within an hour, all surviving sailors from the Annie E. Pierce had safely landed on shore.

Sadly, one of the seaman had been killed by a rogue wave before grounding. The crew had sought safety in the vessel’s cabin as they passed through the breakers, and the force of the wave threw the cabin doors open, fatally injuring First Mate Alonzo Driscoll, who had been attempting to hold them closed.

The continued assault of the waves on the vessel forced the remaining sailors to climb the riggings when another large wave swept over the schooner and broke Captain Joseph R. Somers’ leg.

Upon landing on shore, Captain Somers was transferred to the station in the keeper’s cart where he received as much treatment as Keeper Midgett could provide with his medicine chest. Efforts were made to have a doctor come from the mainland, but the bad weather continued for several days, which prevented additional medical help from arriving.

About a week after the incident, a surgeon arrived via a revenue cutter that had been sent by the Department, and Captain Somers was finally able to receive the medical assistance he needed.

During the wait for the cutter to arrive, the surfmen were eventually able to launch the surfboat to retrieve Mate Driscoll as well as clothing for the survivors. A funeral service was held, and a grave was added to a neighborhood cemetery. After the departure of the seamen, an investigation was launched due to the death of the first mate. However, a notarized statement from the survivors indicated the loss of life and the captain’s injury were not the fault of the lifesaving crews, and happened before the vessel grounded. They were grateful the stations responded so promptly and gave all possible assistance.

All in a Day’s Work at the Kitty Hawk Life-Saving Station

Sometimes it’s about being a navigator: On December 11, 1896, Keeper Samuel J. Payne and one surfman from the Kitty Hawk Life-Saving Station responded to a steam signal and found the Teaser had grounded lightly when she missed the channel. Soon, they were able to get her floated where Keeper Payne then guided her through the channel into the Currituck Sound. Before moving back to the surfboat, Keeper Payne gave the Teaser’s master further directions for proceeding to her destination.

For more stories like these, visit the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station where history is alive.