One day, when I was visiting my friend and mentor, the great Outer Banks historian David Stick, at his Kitty Hawk home, we discussed the durability of historical statements.

In the course of our discussion, he made a comment for which I had no reply: “You know, Kevin, in the past 50 years, not once has someone brought to my attention a factual error in any of my books.” At that moment I probably had the same thought that occurred to David’s other friends—silence is golden. That’s because I probably could have named at least three mistakes that David had made, but I did not want to be the first to point those out to him.

David Stick was rightfully proud of his research accomplishments and scholarship. He was a stickler for accuracy. But any historian who has published hundreds of thousands of words on a broad range of historical subjects in a dozen books is bound to make a mistake or two along the way, especially when there are always sources of information that elude the scrutiny of the most diligent researcher.

That historians make mistakes is not uncommon; what is rare these days are historians, or their publishers, who admit to their mistakes. I remember a time when loose sheets of paper containing lists of errata (production errors) or corrigendum (author errors) could be found in books. Not anymore.

Today we live in a bewildering age of propaganda, misinformation, variable “facts,” digitally altered images, blurred realities, and the unaccountability of content creators. Our time, classified by some as a “post-truth society,” might be fairly viewed as a Barnum and Bailey world, a trip through a carnival funhouse of distorting mirrors where reality is warped and nothing is as it seems.

History is often like that, too. Mark Twain described his view of history as looking through a kaleidoscope “constructed out of the broken fragments of antique legends.” My concept of observing the events of the past is like looking through the thick bottom of a green-tinted soda bottle.

The consequence of a historian publishing a factual error is that, while history does not necessarily repeat itself, historians frequently repeat each other. An error made 300 years ago becomes etched in stone by repetition over three centuries, and like kudzu, it is impossible to eradicate.

So, before it’s too late, I need to correct an error I have made regarding the history of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse’s first-order Fresnel lens, manufactured by the Henry-Lepaute company of Paris, and delivered to the United States in 1853. I unexpectedly discovered my mistake last week while researching previously undiscovered sources and official records from that year in order to unravel a different lighthouse mystery.

In the third edition of my book, “The Lost Light—A Civil War Mystery,” I wrote that the Cape Hatteras lens “dazzled its beholders at the Great Exhibition when it opened on July 14, 1853.” The fact is, the lens had not yet arrived from Paris, so on that date, it dazzled no one at New York’s Crystal Palace.

New Facts

My latest research reveals that on August 12, 1853, Theodore Sedgwick, president of the Crystal Palace Association, wrote to the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury asking for authorization to exhibit the lens at the event. He wrote: “A first class Fresnel light ordered by the lighthouse board, to be put up at Cape Hatteras has arrived from Paris, and is now in the warehouse here. It is not immediately wanted by the lighthouse board, and will not be for sometime, as the tower is not ready for it.”

The request was “cordially approved” but only under certain conditions. The U.S. Lighthouse Board required that the lens’ care had to be supervised by a competent officer/engineer and that it “be returned in the same condition as received, whenever it may be required for the public service. This will not be before the middle of October next.”

The competent officer/engineer assigned to the job was Lt. G. G. Meade of the U.S. Topographical Engineers. Over the summer of 1853, Meade had completed, at Sand Key Lighthouse in Florida, the installation of the “older sister” of the Cape Hatteras lens. It was also a first-order apparatus, (at the time, the largest of its kind designed for the most important seacoast lights), and it had arrived at New York from the Henry-Lepaute company in the autumn of 1849. No one in America had a greater familiarity with the elegant yet extremely complex French technology than Meade. The 38-year-old veteran of the Mexican-American war was soon on his way to Manhattan.

In my book, and also in articles I have written for the “Island Free Press,” I stated that almost ten years “to the day” after Meade had assembled the Cape Hatteras lens at the Crystal Palace, he was better known as Major General (volunteers) George G. Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, who stopped General Robert E. Lee’s advancing army at Gettysburg. Well, that statement—almost ten years “to the day”—was not entirely accurate either, but close. Meade completed the Cape Hatteras lens exhibit by September 20, 1853, according to press reports. Regardless, little could anyone imagine the impact that the tall, dignified lighthouse engineer would have a decade later on the future of the United States.

“To Diminish the Perils of the Sea”

The addition of the Cape Hatteras lens exhibit at New York’s Crystal Palace, the nation’s first “world’s fair,” was a widely acclaimed sensation. Many citizens returned to the exhibition a second time just to admire the miraculous French technology in the south nave off 40th Street. It was truly the one marvel that everyone wanted to see, especially in the evenings when the building’s gas lamps flickered dimly and the 24 brilliant beams of light from the Fresnel lens swept the galleries.

The praise in the “Journal of Commerce” could not have been more effusive: “Perhaps nothing in the Crystal Palace—varied as are its collections of whatever is beautiful and useful in art and science—nothing which it contains more strikingly illustrates the great utility of exhibitions of this kind than the Fresnel light. This Light, the last and most approved of all the ingenious and beneficent contrivances resorted to from the days of Homer to our own, to diminish the perils of the sea … is surpassed by nothing in the Palace.”

Clearly, it was recognized that the Fresnel lens in 1853 was a technological epitome of the Industrial Age. One newspaper reported: “The machinery … is exceedingly complicated, and its manufacture requires the utmost care, and involves a complete knowledge of the higher branches of Mathematics.”

Another correspondent writing about the lens in a Raleigh paper was not just effusive but exaggerated the facts by a considerable margin: “It can be seen fifty or sixty miles at sea, and will greatly diminish the terrors of the stormy head-land of Hatteras to the sailor.” That’s what we now call, rather inelegantly, “fake news.” The effective range of the light projected by the lens under ideal conditions at about 150 feet above sea level was estimated to be not much more than about 18 miles.

For 50 cents, attendees were awed by the future Cape Hatteras lens alongside fine sculptures, artwork, and the latest marvels of the world, including Elisha Otis’s miraculous elevator with a safety brake, (imagine how that invention changed the lives of New Yorkers), Eli Whitney’s revolutionary cotton gin, precision steam machinery, a side-stroke fire engine, Samuel Colt’s firearms, and Singer’s latest sewing machine. Ironically, the Henry-Lepaute lens in the south nave was guarded by a bronze sculpture of a dog, reported to be a cross between the St. Bernard and the English mastiff, titled, “The Sentinel.”

For two and a half months, the Cape Hatteras Fresnel lens, “blazing, and revolving, and flashing,” was seen by tens of thousands of exhibition visitors. One writer cleverly described the lens as a “little crystal palace within the Crystal Palace.” But soon, its destiny called; the improvements to the 90-foot-tall stone octagonal tower at Cape Hatteras were progressing, and the lens’ next assignment—and its tumultuous and tragic future—were nigh.

But before Lt. Meade disassembled and packed up the lens along with its pedestal and clockwork mechanism, a photographer commissioned by the Exhibition’s new manager, Phineas T. Barnum, arrived at the Crystal Palace on Thursday, December 1, the day after the fair officially closed for the season. The timing was fortuitous, especially for those of us who cherish the history of Cape Hatteras Lighthouse’s historic lens.

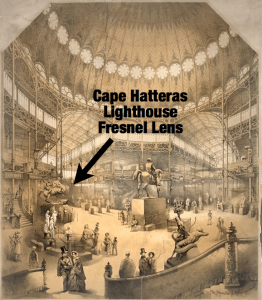

The photographer positioned his heavy oak wood camera stand on the lower gallery in the northeast corner of the 100-foot diameter rotunda, placed his rosewood veneer box camera atop it, slid the bellows backward and delicately adjusted the focus of the brass lens. A remarkable photo was taken, the original glass plate long gone, but the image preserved in a promotional lithograph published by the New York printing firm of Louis Nagel and Adam Weingärtner.

Barely detectable in the south nave, hundreds of feet away, stood the Cape Hatteras lens. It is the only extant image of the lens within the context of the Crystal Palace, although a hand-carved wood engraving of the lens and pedestal before it was removed for Cape Hatteras by Irishman John William Orr resulted in a faithful representation of the apparatus that compares well with the same historic lens at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum.

Meanwhile, at Cape Hatteras in December 1853, during lulls of intermittent nor’easters, a temporary light was placed outside the lighthouse tower about ten feet below the former array of lamps and parabolic reflectors in the lantern room. The iron works atop the old 90-foot-tall stone tower were dismantled and brick masonry was added, elevating the structure by about 35 feet. By March 1854, the already nationally famous Fresnel lens, pedestal, and intricate clockworks by Henry-Lepaute were assembled in the new lantern room of the lighthouse, casting out to lonely mariners at sea the same beams of light that once astonished throngs of New Yorkers at the Crystal Palace.

So, by a serendipitous research discovery, my previous error is hopefully corrected, and as a result, we know more of the unparalleled story. Now, I suppose I need to add little slips of paper into copies my book, “The Lost Light—A Civil War Mystery.”

———————————————

Kevin Duffus is the author of six books on North Carolina maritime history. In 2014, the North Carolina Society of Historians named Kevin Duffus, “North Carolina Historian of the Year.” In 2020, he was honored with the “Research Award” from the National Lighthouse Museum in New York City. Kevin and his family attended the 1964 World’s Fair at Flushing Meadow in Queens, NY, where they saw Michelangelo’s Pietà, loaned by St. Peter’s Basilica, among many other marvels from around the world.