An army of volunteers aim to save sea turtles from the cold weather

By JOE WARD

By JOE WARD

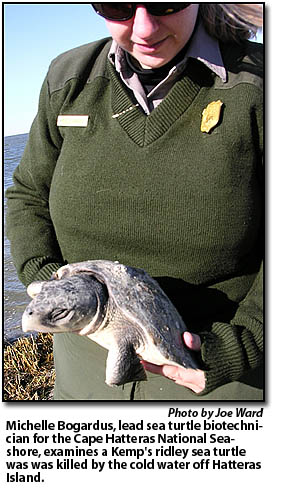

Michelle Bogardus, the Cape Hatteras National Seashore’s 26-year-old lead sea turtle biotechnician on Hatteras Island loves sea turtles.

“They are really interesting animals,” she observed on a recent turtle patrol. “So different from other species. They are in one of the oldest groups of animals in the world.”

But Bogardus does not hesitate to admit that “They don’t really have much brain power.”

And that is part of the reason she was on this particular patrol.

Sea turtles are reptiles with no internal heater, and, unlike some of their landlubber cousins, they do not burrow into the mud and hibernate for the winter. When it gets cold, they are supposed to swim south where it’s warm. Some don’t go in time and are subject to lethargy-inducing “cold-stunning,” an affliction that is ultimately pretty much fatal unless they are rescued.

Bogardus heads a program through which she and a small army of volunteers scour the banks of Hatteras and Ocracoke islands and part of Bodie Island, on both the ocean and sound sides, hoping to find stunned creatures before they succumb.

Sea turtles are endangered or threatened species, in large part due to actions of humans, and Bogardus’ patrols are part of much broader protection programs from government and other organizations.

She and the volunteers find a lot more dead sea turtles than live ones in the late fall and early winter when the water turns cold. In December, for example, they found 123 turtles, only 43 of them still among the living. In January, by the time of this patrol, they’d found another five live turtles and 15 dead ones.

The living turtles are quickly warmed up with dry towels and loaded into volunteer vehicles for a trip to a rehab facility in an outbuilding at the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island. Forty-four made the trip in 2009 — a record, up from 28 in 2008.

But Bogardus said the significance of those numbers is far from clear.

“There were probably just as many last year, if they’d been found,” she said. Her job was created in 2007, and she started organizing patrols. At first, volunteers mostly participated by calling in turtle sightings. Then they started actively looking for turtles.

Last fall she set up a program that trained more than 40 volunteers, and the number of recorded strandings soared.

The trouble is that it’s not really clear to anybody what was going on with cold-stunning before her effort began, at least in terms of numbers for this area. Locals saw dead and dying turtles, she said, but they didn’t really think that much about it.

“We don’t know if this is just what naturally happens. At this point, we’re just trying to deal with the situation as we find it,” she said.

On that particular patrol, Bogardus and Maria Logan, 33, a full-time volunteer who stays in housing provided by the program, drove some beaches just north of Buxton and south of Hatteras village, with a couple of reporters in tow.

Bogardus’ territory includes about 70 miles of beaches on both the oceanside and soundside of the islands. The soundside doesn’t offer nearly as much access to vehicles, and much of the patrolling is done on foot, and by kayak.

Frank Welles, a star volunteer who lives in the Frisco area of Hatteras Island, rescued nine live turtles in his kayak in one December day, bringing his total of live rescues to “20 or so” for the season, Bogardus said. A few days after she spoke, he sent another to rehab.

The patrols try to go out twice a day. Logan had been out earlier on the day in question, and had found a dead green turtle, the species most commonly found in Bogardus’ territory.

Greens are considered an endangered species in Florida, and a threatened one in North Carolina. Under the federal Endangered Species Act, an “endangered” species is one that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range. A “threatened” species is one that is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future.

Bogardus said green sea turtles are one of five species that visit North Carolina waters, one of seven that exist worldwide. Most of the cold-stunned greens found in Hatteras waters are juveniles, she said, 2 to 7 years old, and about the size of a football. They will grow to be 4 feet long and 3 feet wide and reach 400 pounds before they reproduce.

“They aren’t green,” Logan noted. “They’re called greens because of what they eat and because they have green fat. Old-time sailors said greens were the tastiest turtles.”

As the patrol moved along a beach south of the ferry docks in Hatteras village, the women spotted a turtle hunkered on the sand and stopped the truck. It was about the size of a small wash basin and lying very still.

Sometimes such a turtle will show life with the twitch of an eyelid or a flipper that retracts slightly when touched, but Bogardus determined quickly that this one had slipped out of the gene pool. She pointed out that its eyes were dry and papery, a sure sign. Its skin was waxy and had some pinkish splotches that she said indicate cold-stunning.

It was a Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, the second most commonly found in the Hatteras district. Kemp’s ridley turtles are the most endangered species in the world, Bogardus said. They nest “arribada”-style, which is to say, all in one place – a strategy that apparently worked for millennia against most predators, but did not anticipate the effects of humans. They don’t nest in North Carolina, but they love to eat blue crabs, which are plentiful here.

The other sea turtles Bogardus and her troops see are loggerheads and hawksbills. Loggerheads are the major species that nests on the Outer Banks. They sometimes grow to 350 pounds and are very primitive turtles that have been around since the dinosaurs and that get to be “the size of Volkswagens.” Hawksbills, which reach 150 or more pounds in size, are rare in North Carolina.

The two sea turtles that stay clear of these waters are olive ridleys, which are arribada-nesting, similarly-endangered cousins of the Kemp’s, and flatbacks, which live in Australia.

When Bogardus and the group do find live turtles, they transport them to Manteo, first to the Roanoke Island Animal Hospital and the ministrations of Dr. Mary Burkhart.

Burkart and others in her office insert an intravenous tube into a flipper pit to get some fluids into the animal. They take blood samples to check for diseases that might hamper rehabilitation. Pneumonia is a problem they encounter. They check blood sugar and adjust it if necessary. They inject antibiotics if a turtle has an injury, from say a boat prop or an entangled fishing line. They x-ray the turtles to check for intestinal blockages, which are sometimes caused by ingesting plastic objects of various kinds.

As at all other steps in the process, beginning with the volunteer who finds the live turtle, the vet workers write down a lot of information.

The whole effort is about saving turtles, but it is also about research.

Over at the North Carolina Aquarium, for example, where the turtles go when Burkart is through with them, volunteers carefully monitor the turtles’ activity levels, food intake, how much and what the excrete, and various kinds of dimension and weight measurements. They don’t get out of rehab until their feces no longer includes plastic.

On a recent day, Volunteer Kathy Fitz was slicing up small fish there. Her husband, Allen Fitz, and Barbara Helm were feeding the turtles by dropping the slices into the bottoms of plastic tubs to make the turtles find in on their own, a way of gauging their readiness to be released.

“It’s sardines today,” Kathy Fitz said. “Sometimes it’s shrimp. Loggerheads like crabs.”

The rehab facility consists of several large tubs with smaller tubs inside, enough to keep each turtle in its own enclosure so its intake and output can be monitored. The water temperature is 73 degrees, and the room temperature 77.

There were 24 turtles there that day, four short of maximum capacity. When maximum is reached, Bogardus and the volunteers have other facilities north and south where surplus turtles can be sent.

The turtles remain lethargic for a day or two when they enter rehab, then gradually begin moving around and showing interest in eating and such things. The turtles clearly display different personalities, but there was disagreement among the volunteers about whether anybody names them. Apparently, some get names.

The Fitzes and Helm are volunteers from the Network for Endangered Sea Turtles, NEST, a northern Outer Banks non-profit organization that runs the rehab center in cooperation with aquarist Christian Guerreri.

“She’s fantastic,” Kathy Fitz said of Guerreri. “She’s the one who trains us all.”

NEST comes up with the money to run the operation, from grants and donations. Expenses include $200 per turtle for the veterinarian services, if all the turtle needs is a checkup. Otherwise, it’s more. That day there was concern because the organization is not only short of rehab room, but also running low on funds.

For more information on how to help NEST with your contributions, check out http://www.nestonline.org/

Most turtles make it through rehab in a week or two, and then, Bogardus said, they typically get “a free ride to the Gulf Stream,” courtesy of helpful charter boat captains and others. The Gulf Stream is 10 or 20 or so miles out into the ocean, and it is warm.

Part of the adventure for the volunteers is getting the turtles up to Manteo, which they usually do in their own vehicles. And sometimes, as in the case on a recent trip by Anita Bills of Frisco, a patient can take up most of the back of a jeep and be “just barely cold-stunned enough.”

Bogardus said Bills is another of her star volunteers. She is a rapid-talking woman who gets some of her turtle sightings from friends who are kiteboarders, the people who hop on narrow boards and go skimming over the surf towed by large kites in high winds. It’s an activity Bills enjoys herself, even though she lost an arm below the elbow in a dune buggy accident years ago.

“Dan Cramer called and said he had a turtle just north of the haulover,” Bills said.

She drove her jeep to the sound and backed it to the beach.

“He couldn’t get a hand under its head, so he wrapped his arms around the body thing, and it started flailing.” He wrestled it into her jeep, she said, and “that sucker was head-butting me.”

At one point, the turtle snapped the cover clean off the console between the jeep’s front seats which, was enough to alarm even a middle-aged, one-armed kiteboarder. Driving with her good, left hand and managing the rampaging turtle with her stub, she called Bogardus, whose advice was “watch your fingers.”

It’s a story they both enjoy telling, and it ended with the turtle safely in Manteo and no further adventures.

Getting the turtles to Manteo is not the end of the story for Bogardus and her two full-time volunteers, though. Besides Logan, she has Ben Porter. In addition to finding and rescuing live turtles, they gather all kinds of data from the dead ones. That involves necropsies, which have to be done outside because they don’t have a lab. In recent weeks it’s been cold work.

They try to determine cause of death, in case it wasn’t the cold. They determine sex, which in sea turtles is an iffy thing short of a necropsy. They try to determine age, which can be done by cutting into a flipper and using a process something like finding a tree’s age by counting rings. They take various samples, such as a flipper and an eye from each turtle, and genetic samples. It’s all part of the research.

“They try to learn as much as they can, about their habitat, what they eat,” and that sort of thing, said Bills, the ace volunteer, who takes an interest in all of it.

Bills noted that necropsies are not her favorite thing, though. She said she was invited to the dissection of a huge leatherback found on Ocracoke Island not too long ago and she went along to write down any measurements and other data she can help with.

“But I stayed upwind,” she said.

She said she took her own vehicle on that adventure, too, because she wasn’t too interested in riding back across on the Hatteras Inlet ferry in a truck with people who had been doing a necropsy on a turtle.

(Joe Ward is a retired reporter who worked for almost 40 years for The Courier-Journal in Louisville, Ky. He decided to spend part of a very chilly vacation on Hatteras doing some reporting and writing.)

Subject

Name

(required, will not be published)

(required, will not be published)

City :

State :

Your Comments:

May be posted on the Letters to the Editor page at the discretion of the editor.

May be posted on the Letters to the Editor page at the discretion of the editor.

May be posted on the Letters to the Editor page at the discretion of the editor.

May be posted on the Letters to the Editor page at the discretion of the editor.