Commentary: A young Hatteras waterman weighs in on the absurdity of catch shares

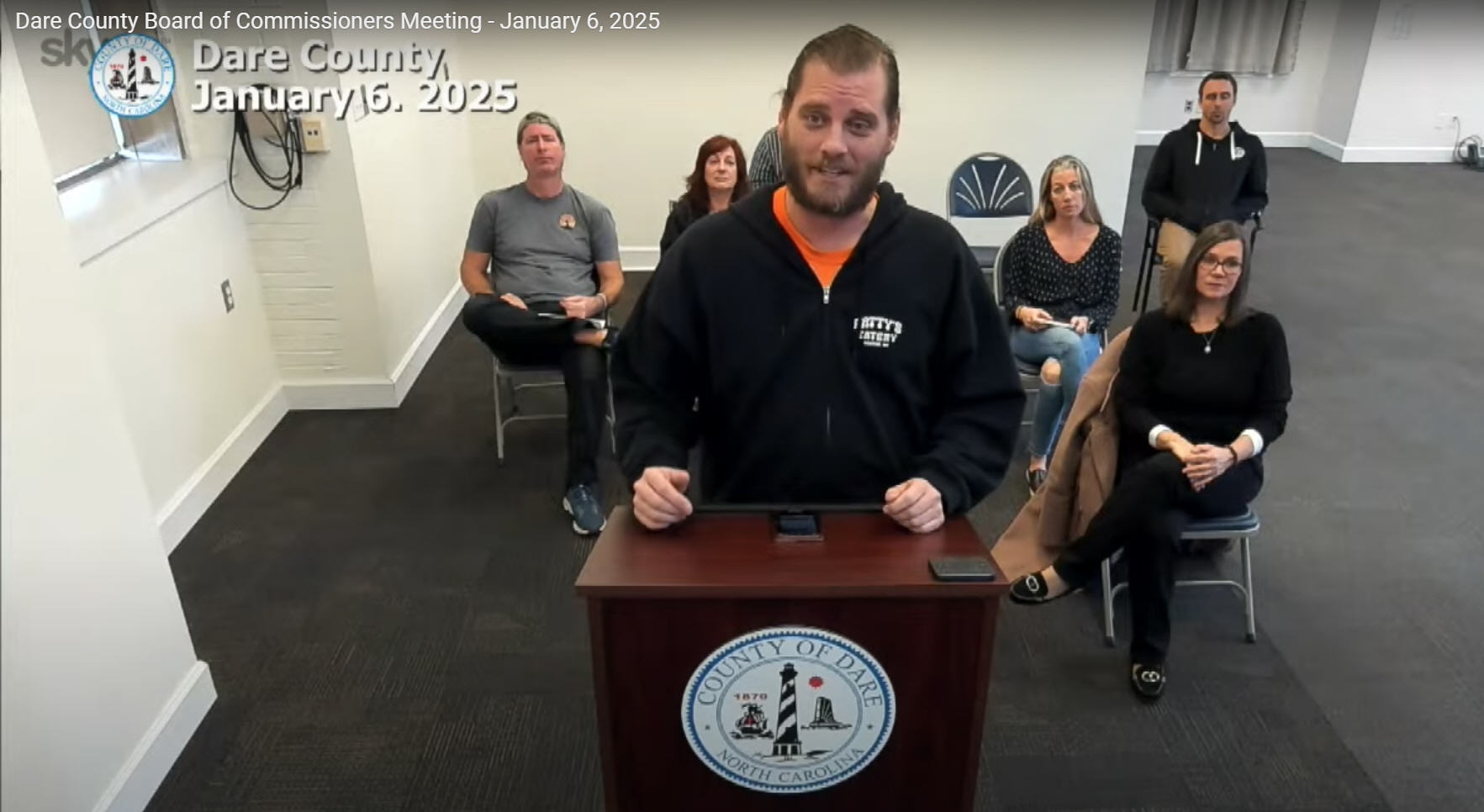

My name is Patrick Martin Caton. I am the owner and operator of the fishing vessel Little Clam. I purchased the boat in 2006, and for the past five years, I have been running recreational fishing charters in the summer and commercial king mackerel fishing in the winter. I operate out of Hatteras, North Carolina, a small village on the Outer Banks, whose cultural identity and economic viability is defined by, and dependent on, its relatively small but extraordinarily experienced fishing fleet.

The fleet here is largely composed of small, individual operations, such as mine, and for many of us, fishing is the only way of life we have ever known. It’s what we grew up doing, because it’s what our fathers and grandfathers did, and it’s what we hope our children may one day be able to do. Unfortunately, thanks to federal and regional policymakers, individual fishermen are being systematically phased-out, and the possibility of supporting one’s self, one’s family, and one’s community through fishing is fast becoming little more than a pipe-dream.

In the five years that I have been fishing, regulations have become increasingly stringent. Each year, quotas and catch limits shrink, new species of fish are outlawed, and more and more of the ocean is deemed off-limits. In addition, astronomical fines and wildly out-of-proportion punishments are imposed on fishermen who fail to comply with these randomly determined and economically devastating regulations.

There’s no doubt that times are hard for fishermen, but they could get much, much worse if Washington autocrat and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) director, Dr. Jane Lubchenco, gets her way.

Lubchenco is the author and steadfast champion of the “catch shares” management system (also known as Limited Access Privilege Programs, or LAPPs), in which the Total Allowable Catch (TAC) is parceled off and essentially sold to the highest bidder.

Make no mistake, this is a radical measure that effectively privatizes a public resource, and its ultimate goal (alternately disguised as “promoting conservation” and “ensuring economic stability”) is to get rid of all but a few, large-scale fishing operations.

The Environmental Defense Fund recently released a report entitled “Sustaining America’s Fisheries and Fishing Communities: An Evaluation of Incentive-Based Management,” in which they make outrageous claims about the benefits of LAPPs. In the report (which was commissioned by the EDF, carried out by the Redstone Group, and funded by the EDF and wealthy conservation foundations), the fishing industry is painted as the epitome of “the tragedy of the commons,” and catch shares are billed as a panacea for its woes.

According to the report, LAPP-managed fisheries boast increased compliance with catch limits, improved science and monitoring, reduced bycatch and habitat destruction, improved safety for fishermen, and sizable economic gains. They claim that LAPPs “[align] fishermen’s economic incentives with society’s conservation goals” and create “sustainable fisheries and vibrant fishing communities.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, none of the people who funded, researched, or authored this report are fishermen.

If they were, they would probably be more concerned with the report’s findings that, under LAPP management “the total number of available crew positions decreased by half” and that “the viability of some small-scale operators and ports may indeed be reduced as fishing businesses adapt.”

They would be equally concerned with the fact that an individual fisherman’s “share” of the resource is a fixed percentage—never changing, even when the TAC goes down, which it does, each year, because Lubchenco and others strive to “err on the side of caution.” Further, these “shares” are designed to be bought and sold, traded and leased. That way, when individuals are inevitably forced out of business, their shares will be purchased (at a fair price, I’m sure) by some large-scale operation—or worse, by private investors and wealthy special interest groups.

So much for those “vibrant fishing communities.”

The hugely adverse impacts that LAPPs will have on small, independent fishing operations is something that Lubchenco & Co. don’t even deny. She has been quoted as saying that catch shares are “a negotiable stock that fishermen can sell as they go out of business, allowing them to exit with some cash.”

Again, decreasing the total number of fishing operations is the unstated goal—and the unsung hero—of LAPPs. Obviously, if there are half as many working watermen, there will be less bycatch and habitat destruction, fewer search and rescue missions (their indicator of improved safety), more money for the fishermen who are lucky enough to still have a job, more monitoring of the remaining fleets, and increased compliance with catch limits.

You don’t need a multi-million dollar study to draw these conclusions.

When the EDF asserts that, in LAPP fisheries, “landings [on average] were 5 percent below the cap,” they not only ignore the 50 percent reduction in fishermen, they neglect to mention that shares can be purchased by third parties. To say that catch limits are more strictly observed under such circumstances—i.e., when scrutiny falls on just a few fishermen and the rights to a part of the TAC belong to entities that don’t actually fish—comically overstates the obvious.

The fact that such outcomes are hailed as the results of LAPP management and touted as indicators of its success is not just poor logic. It is a deliberate and egregious manipulation of data. It represents a proverbial slap-in-the-face to science, and it should call the credibility of this report—and Lubchenco’s leadership—into question.

And the fallacies don’t end there.

Many of the “problems” that LAPPs purportedly solve are issues have been created by the authors of this study for the sole purpose of skewing the perception of LAPPs. For example, this study frequently harps on the “danger” of fishing. While fishing is more dangerous than, say, filing papers or answering phones, it is no more dangerous than any other form of manual labor, and in nearly two decades on the water, I haven’t heard a single fisherman voice concerns about the danger of his work.

Similarly, the EDF report claims that LAPPs “stabilize” employment: “Averaged over a year, a typical crew position before catch shares would have provided the equivalent of just one-half day of work per week. Afterwards, that potential [emphasis mine] rose to more than four days of work per week.”

This statement not only represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of fishing, it demonstrates the lengths to which the authors of this study have gone to manipulate the truth. Lubchenco and the EDF can call this a “welcome increase in full-time employment” if they want. The rest of us should call it what it is—a red herring, thrown in to obscure the fact that the number of jobs available in LAPP-managed fisheries are fewer.

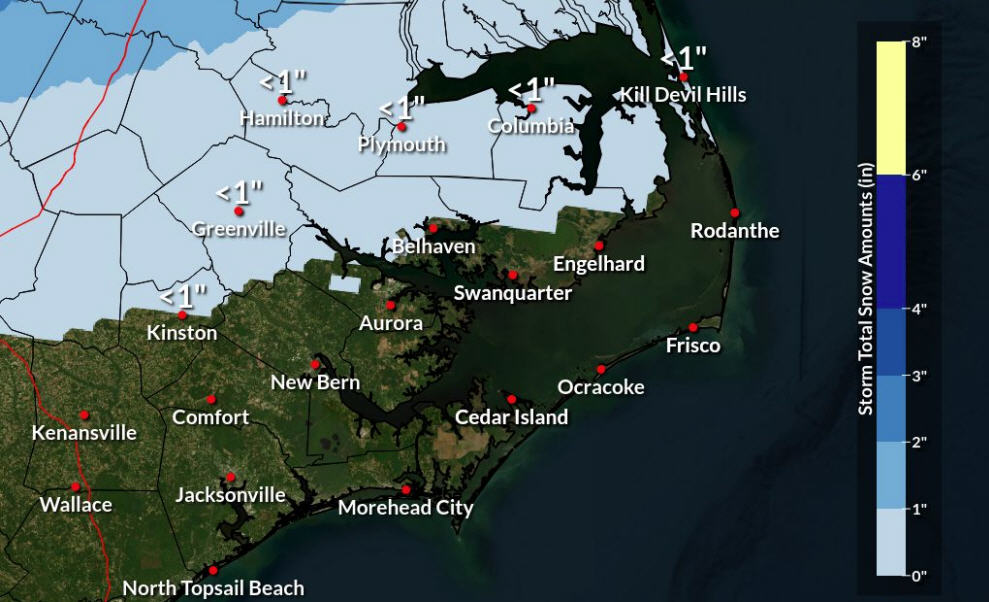

Fishing is not an office job. There exists no such thing as “full-time employment.” The work is inconsistent, inextricably linked to weather and climate events, biological and temporal rhythms, the migratory patterns and reproductive cycles of fish, and other natural phenomena. No one can control these factors—not even NOAA.

To insinuate that LAPPs can make fishing, especially in North Carolina, somehow unseasonal is absolutely absurd. You can’t catch a cobia or a pompano off of Hatteras, in January, regardless of the management plan. And it’s just as impossible to fish during a 30-knot northeast wind under LAPP-management as it is under the current system.

Despite the way it has been billed, implementation of LAPPs is not a conservation measure. It’s quite the opposite, in fact. If NOAA scientists are really concerned with conservation, they would be trying to get rid of the large-scale, multi-fleet operations—the very operations that will flourish under LAPPs—and they would be coming up with ways to support the small-scale, hook-and-line fishermen.

These fishermen have built-in incentives to minimize bycatch and habitat destruction. Such operations are literally not big enough to contribute significantly to overfishing. They are already local, sustainable, and economically viable. Yet, inexplicably, they will be the ones sacrificed on the altar of conservation.

If it sounds hyperbolic or paranoid to assert that getting rid of individual fishermen is the ultimate goal of Lubchenco’s catch shares policy, then consider it from the management angle. It is much easier to manage 10 employees than it is to manage 100. Likewise, it is much easier to control an industry that consists of a few large-scale, multi-fleet operations—that are essentially owned by corporate shareholders— than it is to manage an industry with an abundance of small, independently owned and operated vessels.

Private investors and shareholders are already being recruited, just as Lubchenco is ramping up efforts to force LAPPs on the nation’s fisheries.

At the 2009 Milken Institute Global Conference, which was held in Los Angeles, the new EDF vice president, David Festa, pitched catch shares to wealthy, would-be investors by projecting a 400 percent return on their investments in the program.

Hopefully, you can see that LAPPs are not about conservation, and they are definitely not about fishermen. Their implementation would have devastating consequences for all fishermen in the South Atlantic and would effectively ruin North Carolina’s small fishing communities.

We cannot let Lubchenco and her well-funded, radical environmentalist cronies privatize such a valuable public resource and seize control of one of the few industries that remains dominated by independently owned and operated businesses.