Restoring an Ocracoke salt marsh

“No wetlands, no seafood” is the logo on a bumper sticker from the North Carolina Coastal Federation (NCCF.) It is quite appropriate, therefore, that one of the group’s latest projects is restoring wetlands on Ocracoke Island.

The federation teamed up with the North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching (NCCAT) to replant an acre of marsh at what was formerly the Ocracoke Coast Guard Station and is now an NCCAT teaching campus.

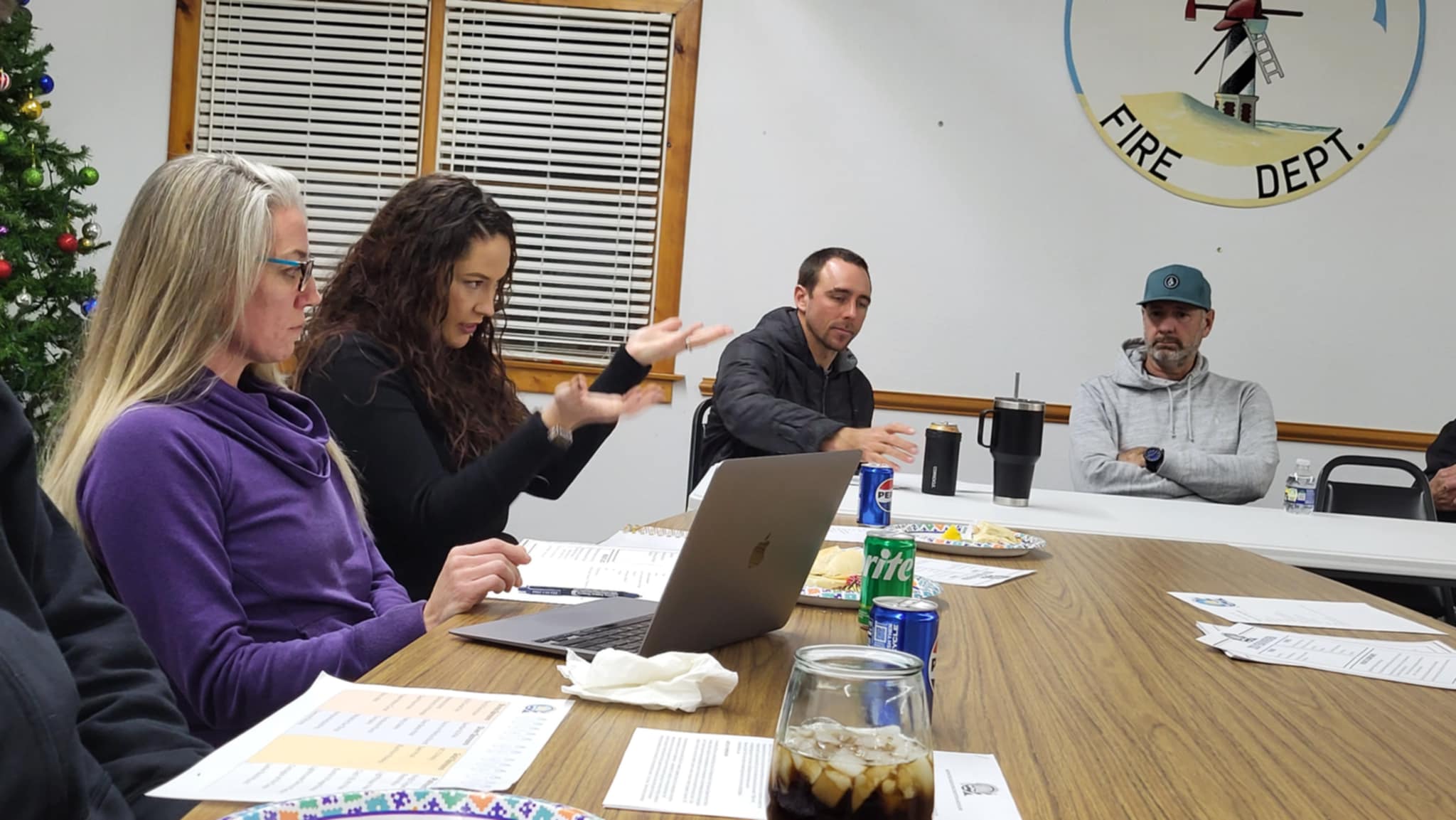

Recognizing the importance of coastal wetlands not just for producing seafood but for a number of ecological reasons, the federation wrote a grant for funding to buy 25,000 marsh grass plants and set aside the last part of April to work with NCCAT teachers, community volunteers, and students from Ocracoke School in planting them.

North Carolina’s coastal wetlands, or salt marshes, edge the soundside shores of barrier islands and the mainland and may extend for hundreds of miles along intercoastal waterways, wherever the water is saline. They filter and clean our ground water, provide flood control, and provide vital habitat, not only for the permanent marsh dwellers, such as ribbed mussels and periwinkles, but for many of our ocean and estuary species as well. Young fish and shrimp find food and shelter in the creeks that meander through salt marshes.

Coastal wetlands are comprised for the most part of three kinds of grasses, each occupying a separate ecological zone in the marsh. The North Carolina Coastal Federation purchased starts of all three species to be set out during the week, and volunteers waded in shallow water and tramped through sand to plant them.

Spartina alterniflora, or marsh cordgrass, grows in the sub-tidal zone, which is inundated by estuary water at each high tide. Its root system, composed of rhizomes, spreads out like a net as it grows. When marsh plants die, they are caught in this net. As they gradually decay, they turn into rich alluvial soil, building more salt marsh and constantly expanding into the sound.

Juncus roemerianus, or black needlerush, inhabits the upper intertidal zone, growing in areas that are covered by saltwater only during unusually high tides. It has needlelike blades which were used by early settlers for sewing.

Spartina patens, known also as salt meadow hay, was planted farther inland, above the high tide line, as it cannot survive regular tidal inundation. This is the grass that used to provide fodder for Ocracoke’s wild ponies.

The project was coordinated with NCCAT’s professional development seminar, “Planet Wetlands: Living Marshlands of the Outer Banks,” designed to educate North Carolina teachers about the important part wetlands play in the ecosystem. The restored wetland will serve as a living classroom for teachers who come to future seminars. The 22 teachers who attended the April seminar participated in the planting, getting hands-on experience in wetland restoration, as did the students from Ocracoke School.

Ocracoke’s U.S. Coast Guard Station property was transferred to the state of North Carolina in 2001, and two years later money was allocated to reclaim the eroded shoreline and provide protection for the property. In 2005, the Moffatt and Nichol engineering firm was engaged to design the shoreline, after which an environmental assessment was developed and the permitting process begun.

NCCF coastkeeper Jan DeBlieu, who helped coordinate the project, said that the federation had long conversations with NCCAT before deciding how to stabilize the shoreline and finally decided upon constructing a rock sill. Construction began in December of 2009, and the rocks were laid so that water and fish could pass through the structure, providing a safe zone where fish can feed.

NCCF educator Sara Hallas worked with the Ocracoke School classes who participated. Rita Thiel was among the teachers who accompanied her class to the site. She described an activity, which she called the rain-drop game, in which her fourth graders acted out the role marsh grasses play in preventing the runoff of pollutants into the sound. She said that the planting provided “an enriching and engaging experience for the students to be involved in, showing how each individual can have a positive impact for the good of their island.

“They worked us hard!” she added. “Teachers and students were tired when we got back!”

Some local Canada geese chopped off the tops of some of the grasses before they were planted, but the project for the most part went well.

Not all of the grasses are expected to live until next year. A 50 percent survival rate is considered a successful planting. NCCF staff will check back on the wetland next spring and replace grasses that have died.

It is hoped that gradually other marsh plants, such as sea oxeye, glasswort, and marsh mallow, will move in and take hold in the marsh, as well as marsh crabs, periwinkles, and similar native salt-marsh inhabitants. Juvenile fish and shrimp have already moved into some of the pools created by the rock sill, and should find the new wetland a safe haven.

The wetland restoration project is a good example of how different organizations can work together to create positive results on many levels.