Daybreak on Ocracoke Island, many winter mornings, finds Ronnie O’Neal heading out to one of his stake blinds in the Pamlico Sound, pursuing a tradition that his grandfather practiced years before.

Earl Gaskins, Beaver Tillett, and several other Ocracokers are doing the same thing, carrying visitors from North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia — some as far away as Michigan — across the shallows of the Pamlico in various kinds of boats, to pursue the sport of waterfowl hunting.

Hunting has been an important part of life on Ocracoke and Hatteras islands since the days of the first European settlers. Ducks and geese have always been the main target, but in the past islanders hunted not only waterfowl but also rails, robins, shorebirds (sanderlings), and cedar waxwings. Today, hunting is a recreational activity for most, but there are still many islanders who count on a few ducks and geese to supplement their meat supply.

Market hunting or “gunning” was the term used to describe hunting waterfowl in earlier years to sell to restaurants and other buyers. Before the Migratory Bird Act of 1917 was passed, hunters shot and sold dozens of birds per day. They packed the fowl, still wearing their feathers, in flour barrels, sometimes placing a stovepipe filled with ice in the middle. They shipped them north to New York, by way of Morehead City, New Bern, Washington, N.C., or Norfolk, Va.

In an interview before his death at the age of 96, Thurston Gaskill of Ocracoke talked about hunting geese and ducks with his father, Captain Bill. They hunted from blinds and batteries, Thurston said, using live and wooden decoys, with the goal of selling them. During the great freeze of 1918, they were trapped for three weeks on Beacon Island, an island off the coast of Ocracoke, and while there, they shot 325 ducks, brant, and geese. New restrictions brought an end to this kind of hunting and, as Thurston stated, “There are not as many birds as there used to be.”

Daybreak on Ocracoke Island, many winter mornings, finds Ronnie O’Neal heading out to one of his stake blinds in the Pamlico Sound, pursuing a tradition that his grandfather practiced years before.

Earl Gaskins, Beaver Tillett, and several other Ocracokers are doing the same thing, carrying visitors from North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia — some as far away as Michigan — across the shallows of the Pamlico in various kinds of boats, to pursue the sport of waterfowl hunting.

Hunting has been an important part of life on Ocracoke and Hatteras islands since the days of the first European settlers. Ducks and geese have always been the main target, but in the past islanders hunted not only waterfowl but also rails, robins, shorebirds (sanderlings), and cedar waxwings. Today, hunting is a recreational activity for most, but there are still many islanders who count on a few ducks and geese to supplement their meat supply.

Market hunting or “gunning” was the term used to describe hunting waterfowl in earlier years to sell to restaurants and other buyers. Before the Migratory Bird Act of 1917 was passed, hunters shot and sold dozens of birds per day. They packed the fowl, still wearing their feathers, in flour barrels, sometimes placing a stovepipe filled with ice in the middle. They shipped them north to New York, by way of Morehead City, New Bern, Washington, N.C., or Norfolk, Va.

In an interview before his death at the age of 96, Thurston Gaskill of Ocracoke talked about hunting geese and ducks with his father, Captain Bill. They hunted from blinds and batteries, Thurston said, using live and wooden decoys, with the goal of selling them. During the great freeze of 1918, they were trapped for three weeks on Beacon Island, an island off the coast of Ocracoke, and while there, they shot 325 ducks, brant, and geese. New restrictions brought an end to this kind of hunting and, as Thurston stated, “There are not as many birds as there used to be.”

Daybreak on Ocracoke Island, many winter mornings, finds Ronnie O’Neal heading out to one of his stake blinds in the Pamlico Sound, pursuing a tradition that his grandfather practiced years before.

Earl Gaskins, Beaver Tillett, and several other Ocracokers are doing the same thing, carrying visitors from North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia — some as far away as Michigan — across the shallows of the Pamlico in various kinds of boats, to pursue the sport of waterfowl hunting.

Hunting has been an important part of life on Ocracoke and Hatteras islands since the days of the first European settlers. Ducks and geese have always been the main target, but in the past islanders hunted not only waterfowl but also rails, robins, shorebirds (sanderlings), and cedar waxwings. Today, hunting is a recreational activity for most, but there are still many islanders who count on a few ducks and geese to supplement their meat supply.

Market hunting or “gunning” was the term used to describe hunting waterfowl in earlier years to sell to restaurants and other buyers. Before the Migratory Bird Act of 1917 was passed, hunters shot and sold dozens of birds per day. They packed the fowl, still wearing their feathers, in flour barrels, sometimes placing a stovepipe filled with ice in the middle. They shipped them north to New York, by way of Morehead City, New Bern, Washington, N.C., or Norfolk, Va.

In an interview before his death at the age of 96, Thurston Gaskill of Ocracoke talked about hunting geese and ducks with his father, Captain Bill. They hunted from blinds and batteries, Thurston said, using live and wooden decoys, with the goal of selling them. During the great freeze of 1918, they were trapped for three weeks on Beacon Island, an island off the coast of Ocracoke, and while there, they shot 325 ducks, brant, and geese. New restrictions brought an end to this kind of hunting and, as Thurston stated, “There are not as many birds as there used to be.”

After market hunting was made illegal, “guiding” — taking visitors out to duck blinds so they could hunt — became an important occupation. During the early years of the 20th century, hunting for waterfowl was a big part of life on Ocracoke and Hatteras islands. Hunt clubs at Green Island, Quork Hammock, and Beacon Island on Ocracoke and Gull Island and Gooseville at Hatteras drew men from all parts of the eastern seaboard to shoot waterfowl.

The Green Island Club was formed in 1923 at the north end of Ocracoke, by a group of men primarily from Pittsburgh. It was later purchased by “a sportsman gentleman” by the name of Sam Jones, from the Hyde County mainland, who also built Ocracoke’s “Castle,” which is now restored as The Castle Bed and Breakfast.

Quork Hammock Club, also located at Ocracoke’s north end, was built by David Keppel, an art critic and curator from the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Ocracoker Stanley Wahab later bought it. Uriah “Ri” Garrish was its caretaker for a while, and his daughter Ellen Robinson recalled in an earlier interview that “There were four, five, maybe six houses there…I remember all these geese and ducks lined up hanging on the porch…hundreds of them…”

Ri Garrish took visitors out to hunt, among them renowned hunter and author Rex Beach, whose book, “Oh Shoot,” described Ocracoke as the center of the goose-hunting industry.

Captain Bill Gaskill, according to his son Thurston, owned a hunting club on Beacon Island. The wooden building was about 30-by-26 feet with a fireplace and rooms lined with red paper. As a guide, he carried hunters to the camp in a big, flat-bottomed skiff made of cypress and cedar, and they would stay for four to five days.

Ocracoke native Clinton Gaskill remembered accompanying his father, Benjamin Gaskill, to a club at Harbor Island, which lay between Ocracoke and Atlantic, N.C.

“The storm of ‘33 washed it away,” he recalled, but before that, “There was a big hunting camp, and Daddy cooked for all the men who came to hunt.”

They used batteries and live decoys, which would honk the wild birds in.

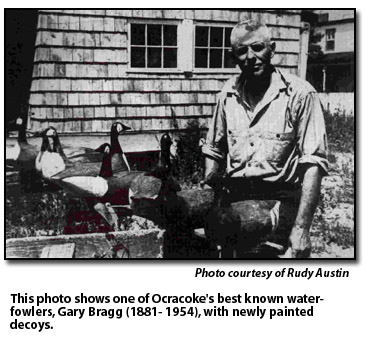

Clinton later worked as a hunting guide for Gary Bragg, one of Ocracoke’s most famous waterfowlers and the owner of Cedar Grove Inn. Dr. Edgar Burke, artist, writer, and decoy-carver, was often a guest of Bragg’s.

On Hatteras Island, the Gooseville Gun Club was built in the late 1920s or early ‘30s on property purchased from Andrew Austin near where the Hatteras Inlet Coast Guard Station is today. Luther Austin later became its caretake, and remained so until 1986.

The Gull Island Club was built on a small island off northern Hatteras Island in the early 1900s. It was destroyed in 1932 or ‘33 by a winter storm and was never rebuilt.

After market hunting was made illegal, “guiding” — taking visitors out to duck blinds so they could hunt — became an important occupation. During the early years of the 20th century, hunting for waterfowl was a big part of life on Ocracoke and Hatteras islands. Hunt clubs at Green Island, Quork Hammock, and Beacon Island on Ocracoke and Gull Island and Gooseville at Hatteras drew men from all parts of the eastern seaboard to shoot waterfowl.

The Green Island Club was formed in 1923 at the north end of Ocracoke, by a group of men primarily from Pittsburgh. It was later purchased by “a sportsman gentleman” by the name of Sam Jones, from the Hyde County mainland, who also built Ocracoke’s “Castle,” which is now restored as The Castle Bed and Breakfast.

Quork Hammock Club, also located at Ocracoke’s north end, was built by David Keppel, an art critic and curator from the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Ocracoker Stanley Wahab later bought it. Uriah “Ri” Garrish was its caretaker for a while, and his daughter Ellen Robinson recalled in an earlier interview that “There were four, five, maybe six houses there…I remember all these geese and ducks lined up hanging on the porch…hundreds of them…”

Ri Garrish took visitors out to hunt, among them renowned hunter and author Rex Beach, whose book, “Oh Shoot,” described Ocracoke as the center of the goose-hunting industry.

Captain Bill Gaskill, according to his son Thurston, owned a hunting club on Beacon Island. The wooden building was about 30-by-26 feet with a fireplace and rooms lined with red paper. As a guide, he carried hunters to the camp in a big, flat-bottomed skiff made of cypress and cedar, and they would stay for four to five days.

Ocracoke native Clinton Gaskill remembered accompanying his father, Benjamin Gaskill, to a club at Harbor Island, which lay between Ocracoke and Atlantic, N.C.

“The storm of ‘33 washed it away,” he recalled, but before that, “There was a big hunting camp, and Daddy cooked for all the men who came to hunt.”

They used batteries and live decoys, which would honk the wild birds in.

Clinton later worked as a hunting guide for Gary Bragg, one of Ocracoke’s most famous waterfowlers and the owner of Cedar Grove Inn. Dr. Edgar Burke, artist, writer, and decoy-carver, was often a guest of Bragg’s.

On Hatteras Island, the Gooseville Gun Club was built in the late 1920s or early ‘30s on property purchased from Andrew Austin near where the Hatteras Inlet Coast Guard Station is today. Luther Austin later became its caretake, and remained so until 1986.

The Gull Island Club was built on a small island off northern Hatteras Island in the early 1900s. It was destroyed in 1932 or ‘33 by a winter storm and was never rebuilt.

After market hunting was made illegal, “guiding” — taking visitors out to duck blinds so they could hunt — became an important occupation. During the early years of the 20th century, hunting for waterfowl was a big part of life on Ocracoke and Hatteras islands. Hunt clubs at Green Island, Quork Hammock, and Beacon Island on Ocracoke and Gull Island and Gooseville at Hatteras drew men from all parts of the eastern seaboard to shoot waterfowl.

The Green Island Club was formed in 1923 at the north end of Ocracoke, by a group of men primarily from Pittsburgh. It was later purchased by “a sportsman gentleman” by the name of Sam Jones, from the Hyde County mainland, who also built Ocracoke’s “Castle,” which is now restored as The Castle Bed and Breakfast.

Quork Hammock Club, also located at Ocracoke’s north end, was built by David Keppel, an art critic and curator from the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Ocracoker Stanley Wahab later bought it. Uriah “Ri” Garrish was its caretaker for a while, and his daughter Ellen Robinson recalled in an earlier interview that “There were four, five, maybe six houses there…I remember all these geese and ducks lined up hanging on the porch…hundreds of them…”

Ri Garrish took visitors out to hunt, among them renowned hunter and author Rex Beach, whose book, “Oh Shoot,” described Ocracoke as the center of the goose-hunting industry.

Captain Bill Gaskill, according to his son Thurston, owned a hunting club on Beacon Island. The wooden building was about 30-by-26 feet with a fireplace and rooms lined with red paper. As a guide, he carried hunters to the camp in a big, flat-bottomed skiff made of cypress and cedar, and they would stay for four to five days.

Ocracoke native Clinton Gaskill remembered accompanying his father, Benjamin Gaskill, to a club at Harbor Island, which lay between Ocracoke and Atlantic, N.C.

“The storm of ‘33 washed it away,” he recalled, but before that, “There was a big hunting camp, and Daddy cooked for all the men who came to hunt.”

They used batteries and live decoys, which would honk the wild birds in.

Clinton later worked as a hunting guide for Gary Bragg, one of Ocracoke’s most famous waterfowlers and the owner of Cedar Grove Inn. Dr. Edgar Burke, artist, writer, and decoy-carver, was often a guest of Bragg’s.

On Hatteras Island, the Gooseville Gun Club was built in the late 1920s or early ‘30s on property purchased from Andrew Austin near where the Hatteras Inlet Coast Guard Station is today. Luther Austin later became its caretake, and remained so until 1986.

The Gull Island Club was built on a small island off northern Hatteras Island in the early 1900s. It was destroyed in 1932 or ‘33 by a winter storm and was never rebuilt.

During the early years, hunters used batteries, which were narrow, watertight, coffin-like boxes that floated at water level. Hunters lay down in them as they waited for the birds to fly in, attracted by live decoys, often Canada geese raised in the village for that purpose. Iron decoys were attached to the sides of the batteries to hold them low in the water. They were extremely uncomfortable but very successful, so much so that their use was outlawed in 1935. Not long afterwards, the use of live decoys was also banned.

In the 1940s, hunters began using concrete pit blinds, also called sinkboxes, which were similar to batteries but were stationary and made with a concrete frame. Rolling blinds were often used on land, similar to regular blinds but with rollers that made them moveable.

Today limits and license requirements reduce the number of birds that can be taken. Most waterfowl hunters use stake blinds, which sit out in the marsh or in the sound and are reachable by boat.

Jack Dudley, author of “Mattamuskeet & Ocracoke Waterfowl Heritage,” described them as “a pulpit on four posts.” They look like little houses sitting above the water, and some are quite comfortably furnished. Plastic decoys have, for the most part, replaced the canvas and wooden decoys of bygone days.

Pintails, blackheads (also known as bluebills), red heads, buffleheads, and brant are the species that today’s hunters are seeing.

It’s a good year so far, according to hunting guide Earl Gaskins, probably because of the cold weather that settled on the islands after Thanksgiving. He and Beaver Tillett have eight or 10 stake blinds, and they use Carolina skiffs to carry hunters out to them. They have been booked, he says, every day since hunting season began Dec. 18. It usually runs through January.

Ronnie O’Neal has been busy with professional guiding as well, but he especially enjoys taking out his friends and giving the fowl to islanders who enjoy the meat.

The tradition of waterfowl hunting, while changed in many ways from the past, continues today on both islands.

During the early years, hunters used batteries, which were narrow, watertight, coffin-like boxes that floated at water level. Hunters lay down in them as they waited for the birds to fly in, attracted by live decoys, often Canada geese raised in the village for that purpose. Iron decoys were attached to the sides of the batteries to hold them low in the water. They were extremely uncomfortable but very successful, so much so that their use was outlawed in 1935. Not long afterwards, the use of live decoys was also banned.

In the 1940s, hunters began using concrete pit blinds, also called sinkboxes, which were similar to batteries but were stationary and made with a concrete frame. Rolling blinds were often used on land, similar to regular blinds but with rollers that made them moveable.

Today limits and license requirements reduce the number of birds that can be taken. Most waterfowl hunters use stake blinds, which sit out in the marsh or in the sound and are reachable by boat.

Jack Dudley, author of “Mattamuskeet & Ocracoke Waterfowl Heritage,” described them as “a pulpit on four posts.” They look like little houses sitting above the water, and some are quite comfortably furnished. Plastic decoys have, for the most part, replaced the canvas and wooden decoys of bygone days.

Pintails, blackheads (also known as bluebills), red heads, buffleheads, and brant are the species that today’s hunters are seeing.

It’s a good year so far, according to hunting guide Earl Gaskins, probably because of the cold weather that settled on the islands after Thanksgiving. He and Beaver Tillett have eight or 10 stake blinds, and they use Carolina skiffs to carry hunters out to them. They have been booked, he says, every day since hunting season began Dec. 18. It usually runs through January.

Ronnie O’Neal has been busy with professional guiding as well, but he especially enjoys taking out his friends and giving the fowl to islanders who enjoy the meat.

The tradition of waterfowl hunting, while changed in many ways from the past, continues today on both islands.

During the early years, hunters used batteries, which were narrow, watertight, coffin-like boxes that floated at water level. Hunters lay down in them as they waited for the birds to fly in, attracted by live decoys, often Canada geese raised in the village for that purpose. Iron decoys were attached to the sides of the batteries to hold them low in the water. They were extremely uncomfortable but very successful, so much so that their use was outlawed in 1935. Not long afterwards, the use of live decoys was also banned.

In the 1940s, hunters began using concrete pit blinds, also called sinkboxes, which were similar to batteries but were stationary and made with a concrete frame. Rolling blinds were often used on land, similar to regular blinds but with rollers that made them moveable.

Today limits and license requirements reduce the number of birds that can be taken. Most waterfowl hunters use stake blinds, which sit out in the marsh or in the sound and are reachable by boat.

Jack Dudley, author of “Mattamuskeet & Ocracoke Waterfowl Heritage,” described them as “a pulpit on four posts.” They look like little houses sitting above the water, and some are quite comfortably furnished. Plastic decoys have, for the most part, replaced the canvas and wooden decoys of bygone days.

Pintails, blackheads (also known as bluebills), red heads, buffleheads, and brant are the species that today’s hunters are seeing.

It’s a good year so far, according to hunting guide Earl Gaskins, probably because of the cold weather that settled on the islands after Thanksgiving. He and Beaver Tillett have eight or 10 stake blinds, and they use Carolina skiffs to carry hunters out to them. They have been booked, he says, every day since hunting season began Dec. 18. It usually runs through January.

Ronnie O’Neal has been busy with professional guiding as well, but he especially enjoys taking out his friends and giving the fowl to islanders who enjoy the meat.

The tradition of waterfowl hunting, while changed in many ways from the past, continues today on both islands