By

Part of a history series examining each of North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties.

Coastal North Carolina is made up of a wide variety of historic towns, marshes, sounds and beaches but only a small percentage of the coastal area is the Outer Banks, that set of barrier islands most tourists consider when they think about the state’s coast.

Much of the Outer Banks is in Dare County, which stretches from Old Caffey’s Inlet south to Hatteras Inlet, and west on the mainland to the Alligator River, according to “The formation of the North Carolina counties, 1663-1943” by David Leroy Corbitt.

Dare County played a key role in two early North Carolina settlements. It was the site of the Sir Walter Raleigh colonies, the first attempts by the English to permanently settle in the New World. The last of these colonies, John White’s 1587 colony, disappeared sometime between 1587 and 1590.

Eighty years later, the land was part of the original Albemarle settlements. One of the earliest Albemarle land grants was in 1663 to one of the Lords Proprietor, Sir John Colleton, for the Outer Banks island now known as Collington Island. This plantation was not profitable for agriculture and soon failed. But it introduced the practice of livestock cultivation on the Outer Banks, a popular method of economic activity since animals on islands did not need to be fenced.

Life on the Outer Banks changed little for the next two centuries.

County, of which most of Dare County was then a part, had an enslaved population that was 33% of the total population according to the 1860 Hergesheimer map, one of the lowest percentages in eastern North Carolina.

The area received a jolt in 1861 with the beginning of the Civil War. Union armies captured Hatteras and then Roanoke Island in 1862 in a major operation led by Union general, Ambrose Burnside.

Hatteras was also supposed to be the center of a new loyal government for the state in 1861. The government never received support outside of Hatteras, however, and fell apart within a few months. During the war, Roanoke Island became a center for settlement known as the Freedmen’s Colony, where plantations were seized and handed over to freed African Americans.

Although Freedmen’s Colony on Roanoke Island only lasted until the end of the war, African Americans continued to play a role in the county long afterwards.

While many left due to a lack of arable land, some African Americans stayed. One was Richard Etheridge, who lived on Roanoke Island before eventually enlisting in the Union Army and being deployed to Texas.

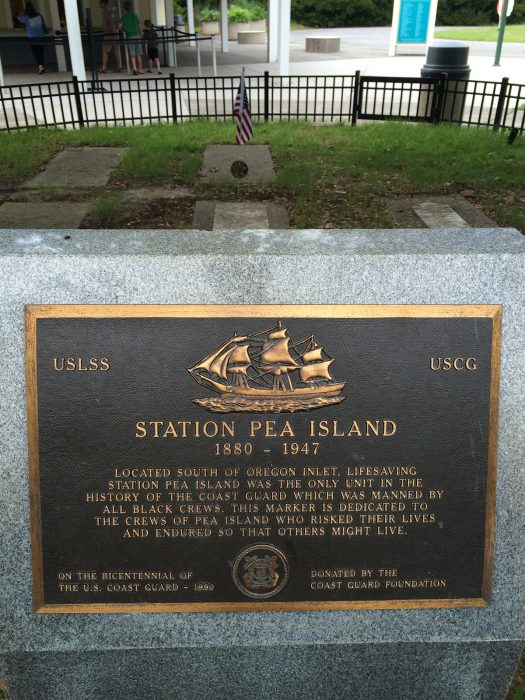

After the war, Etheridge came back and led the Pea Island Lifesaving Station, the only all-African American crew in the lifesaving service. Etheridge served on the post for 21 years, dying on the job in 1900. The Coast Guard, the successor to the United States Life-Saving Service, awarded Etheridge and his crew the Gold Lifesaving Medal in 1996, and a statue honoring Etheridge was dedicated in Manteo in 2010.

In 1870, the eastern section of Tyrrell County pushed for new local representation. Many residents on the Outer Banks were miles away from the county courthouse in Columbia. They received a new county that year named for Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the New World. The formation of Dare County led immediately to the establishment of Manteo, the county seat, where a courthouse was built in 1904.

Versions of the county’s two major lighthouses, Cape Hatteras and Bodie Island, were built that decade and have served as symbols for the Outer Banks ever since. County formation also set in motion a uniquely loose governing structure, owing to the difficulty of transportation in the mostly aquatic county. As David Stick wrote in his history of Dare County, “As recently as the 1940s it was frequently said that there were two ways to do things in North Carolina: either the Dare County way, or the way they were done in the other ninety-nine counties.”

The early 20th century witnessed several significant moments in the history of Dare County. In 1903, the Wright Brothers made the first successful manned, powered flight from a particularly tall dune at Kill Devil Hills. This great achievement led to the county being internationally known, with a triumphant monument built overlooking the beach in 1932. The monument, Wright Brothers National Memorial, administered by the National Park Service, became well known in its own right and was the scene of the climax in the 1983 science fiction film, “Brainstorm.”

The Wright Brothers brought fame and a handful of tourists to the Outer Banks. But a construction project finished in 1928 changed the area forever. Once the first span bearing the name opened, the Washington Baum Bridge turned Dare County into one of the most visited areas in the state. The current Baum bridge was completed in 1994.

That first bridge was soon joined by the Wright Memorial Bridge in Currituck County in 1930 and, later, the Bonner Bridge in 1963. David Stick notes that as a result of bridge construction, the developed areas of Outer Banks beaches expanded from around a mile in the 1910s to 75 miles by 1970.

The past 70 years have seen considerable buildup throughout Dare County.

David Stick, the historian, became a major developer of the community known as Southern Shores. Dare County’s population as of 2021 is 37,826, a 685% increase from 1950, and more than 10 times the population of neighboring Tyrrell County. The only areas that have escaped the influx of tourists and new residences are the swamps on the mainland and the areas protected by the federal government.

Much of the northern tip of Roanoke Island is part of the federal Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, which operates the theater where the outdoor drama, “The Lost Colony” is staged every summer. There is also a wildlife refuge on Pea Island as well as the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, the first national seashore.

Dare County, unlike a number of other coastal counties, has substantial economic activity and nearly as many tourists as its infrastructure can handle. There are more restaurants in one small Outer Banks hamlet than in entire Albemarle region. But Dare County is facing the increasingly evident effects of climate change and rising sea levels. Balancing the desires of tourists with the need to remain resilient and protect natural resources will continue to be a challenge.

Just leave climate change out of the columns as it immediately tunes out a good portion of your readers and tricks others into thinking the houses of recent which succumbed to ocean happened because of global warming. These two houses were built in the 80’s and had vast beach in front of them. When built we were about 50 years from when the dunes were built in the 30’s, which is what created the situation we are now in (The beach was shrinking then, but was not a concern and may not have been noticed given the size of the beach). For those who do not know the dunes were built by the CCC to eliminate nuisance flooding that regularly occurred as the ocean pushed sand back towards the sound as the island slowly retreated towards the mainland. There were no dunes other than natural mounds and the water had free reign to ebb and flow to the sound carrying sand with it. The impact was substantially less as their was nothing to stop them and the wave action was spread over a long distance versus a very small impact zone which carves the beach away in short order. Combine that with no sand moving to the sound and you have a shrinking island. In the end it would not have mattered if it were the dunes or the slow migration of sand, these houses would have fallen anyway, but it might have taken a longer time for it to happen. Where man has screwed up on the barrier island is drawing a line in the sand and trying to defend against the ocean, which is impossible. Pumping sand onto the beach is a folly and never-ending process. Meddling with nature without considering side effects never ends well which is something government has done on many occasions.