North Carolina sounds are losing seagrass, an indicator of the state’s water quality.

According to a recently published metric report by Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership, or APNEP, there’s been a net loss of at least 5% between 2006 and 2013 of the high-salinity submerged aquatic vegetation, or SAV, habitat in the Albemarle-Pamlico estuarine system, which is the second-largest in the United States.

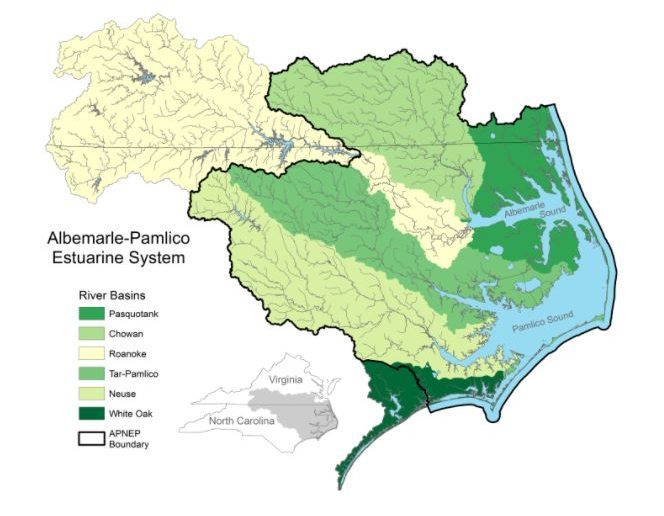

APNEP works to identify, protect, restore and monitor the natural resources of the Albemarle-Pamlico region, which has more than 3,000 square miles of estuarine waters and a land area of 28,000 square miles. Pasquotank, Chowan and Roanoke basins flow into Albemarle Sound, and the Tar-Pamlico and Neuse basins into Pamlico Sound. Rivers of the White Oak basin flow into the southern sounds — Core, Back, and Bogue – of the region.

Also known as seagrass or underwater grasses, this vegetation plays various roles in keeping Albemarle-Pamlico Estuarine System waters healthy by providing habitat, food and shelter for aquatic life as well as absorbing and recycling nutrients and filtering sediment, according to the report.

The seagrasses also act as a barometer of the condition of water. SAV is extremely sensitive to water quality, including nutrient and sediment pollution. The decrease in acreage suggests that the overall health of North Carolina’s estuaries may be worsening, according to APNEP.

“Because these underwater meadows are a public resource that play a vital role in maintaining the diversity, health, and sustainability of North Carolina’s sounds, APNEP has designated seagrass as a ‘valued ecosystem component’ and an ecosystem indicator that should be regularly monitored and assessed,” Dean Carpenter, program scientist for APNEP, told Coastal Review Online.

The data used for the report from two aerial surveys, one from 2006-2007 and the other from 2013, confirm that the state has about 100,000 acres of seagrass, the largest acreage on the east coast, according to APNEP.

However, the overall amount of seagrass meadows in the Albemarle-Pamlico estuary decreased by 5,686 acres or 5.6% between 2006 and 2013, even though the estuary is an ideal habitat for seagrasses to survive.

The seagrass communities in the APNEP region are on the back-barrier shelves of the Outer Banks between the Virginia Dare Memorial Bridge on U.S. 64 that connects Roanoke Island and the Outer Banks, south to Ocracoke Inlet, and on the Outer Banks and mainland shores of Core, Back and Bogue sounds, the report states.

The observed decline in seagrass was more pronounced in the southern end of the study area, which includes Back and Bogue sounds, with a decrease of about 1.5% per year, compared to the central and northern sections of the study area, which declined 0.5% and 1.1% per year, respectively.

It is likely that increased water pollution within the relatively highly populated, densely developed southern region contributed to its higher observed rate of seagrass decline, according to APNEP.

The report cites the state Department of Environmental Quality’s North Carolina Coastal Habitat Protection Plan, which states that major threats to SAV habitat are channel dredging and water quality degradation from excessive nutrient and sediment loading, as well as the emerging threat of accelerated sea level rise, barrier island instability, increasing water temperatures and the expansion of shellfish mariculture.

The data presented in the report cannot be compared to earlier SAV mapping efforts, according to the recent report. While some pre-2000 efforts to map SAV in the APNEP region have been performed, they are limited in scope.

Meanwhile, steps are being taken to rebuild SAV in North Carolina waters.

“One of the leading causes of SAV decline is thought to be decreased water clarity, which inhibits sunlight to reach these aquatic plants,” Carpenter explained.

On the research front, he continued, APNEP is supporting research by University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences faculty involving the refinement of a bio-optical SAV model, which will help determine how different water-quality components such as phytoplankton and turbidity are contributing to decreased water clarity.

“Using this bio-optical model in concert with targeted monitoring data will provide valuable input to future assessments as to where water resource managers need to focus their efforts with respect to mitigating particular constituents, with the intention of improving water clarity,” Carpenter said.

On the policy front, APNEP has a SAV Team that includes partners involved the Coastal Habitat Protection Plan implementation, with SAV being a priority focal habitat during 2020-2021, he said.

“Team partners are also involved in NCDEQ’s Nutrient Criteria Development Plan implementation, with SAV under consideration as a biological endpoint targeted for protection.”

More mapping of seagrass amounts is essential to better understand the current status and long-term trends of SAV in North Carolina. Integration of seagrass mapping with other collaborative environmental monitoring programs is critical to identifying and managing the causes of seagrass decline, APNEP said in a release.

APNEP and partner organizations, including the state Division of Marine Fisheries, coordinated a third study completed in 2019-2020.

The additional survey data being analyzed will help APNEP provide a more complete picture of seagrass status and trends in the Albemarle-Pamlico estuary, and will be used to help develop protection and restoration strategies for the region, including conservation and management actions supported by the North Carolina Coastal Habitat Protection Plan.

The hope is to produce a map by the third quarter of this year, followed by a revised assessment report during the fourth quarter. “Note that such deliverable schedules provide a much more rapid turnaround than before,” he said.

Carpenter said it would be premature to predict what the data will show from the third survey.

“Having documented only two intervals in time roughly six years apart, coupled with a lack of knowledge of SAV baseline (historical) dynamics at the regional scale, a forecast would be premature,” Carpenter explained. “But given the factors influencing SAV condition, it would not surprise me if we discover a continued decline in the resource. An intriguing question when we establish that third point is whether that decline is accelerating, and if so in what areas.”

In the near future, Carpenter said that APNEP is scheduled to produce an initial SAV monitoring plan in the first quarter of this year, “Whose purpose is two-fold: to develop an improved SAV monitoring network that in turn generates targeted data for future SAV assessment reports, and to facilitate the engagement of current and potential partners in that effort.”

The report and an associated interactive map are available online. For more information, visit APNEP’s SAV Monitoring webpage.

The salinity level has got to be much, much higher than it was a couple of decades ago. In 2005 there was still three quarters of a mile of the Hatteras Spit extending beyond the cable crossing where the Hatteras Inlet Light is located. In 2013 there was only a quarter of a mile left. Today, the erosion of the Spit is right up to the Hatteras Inlet Light. The cable crossing was recently modified and improved to protect it from farther erosion. Back in the seventies there was about a mile between the Hatteras Spit and the north end of Ocracoke Island. Today there is probably over two miles between the two, which are both rapidly eroding. That massive expanse has got to be creating a tremendous increase in the salinity of the water in the Pamlico Sound. A rock jetty off the ends of both islands getting back to a more manageable inlet similar to what it was in the seventies would not only decrease the volume of water into the sound. It would more than likely help to stabilize the channel through the inlet, that currently has put a halt to charter, commercial fishing, and even the Coast Guard from navigating the inlet route.