Each fall, the annual migration of birds along the coastal flyways usually results in a rare or unusual species making an appearance, much to the pleasure of bird watchers and nature photographers.

On Hatteras Island, at the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, such birds have been hard to overlook. Anyone driving along Highway 12 through the refuge has probably noticed these enormous, plumed giants.

Fortunately, you won’t need to get up before the rooster crows, go crawling through thick shrub thickets or make silly sounding bird calls to see these feathery beauties. A group of American white pelicans have found the refuge’s waterfowl impoundments much to their liking and have not been shy about mixing in with their Eastern brown pelican cousins. A few white pelicans have shown up here in the past, but the significance this year is that close to 150 of the birds have taken up residence.

I have seen these birds before, flying high overhead at a distance too great to gain a proper appreciation. So with the reports of a large flock out on Pea Island, I figured I wouldn’t be risking much to venture out in search of them. A friend and I took the leisurely route to the Outer Banks, taking advantage of the relaxing ferry ride across Pamlico Sound to Ocracoke, then on to Hatteras and north on Highway 12 until we reached Pea Island in the late afternoon.

Out in one of the impoundments, on a small island covered with a shaggy coat of tall grasses, a group of large white birds were huddled together to ward off the sting of a cold north wind. I quickly dismissed them as great egrets and we headed off to the refuge’s visitor center to get advice to narrow down our search.

The center has a huge bay window overlooking an impoundment with a line of spotting scopes perched on their tripods, inviting us to find these snowy white birds. We spotted two of the birds about a mile away in a restricted section of the refuge. Containing my excitement, I coolly asked one of the refuge staff where we might get a better look at the pelicans.

It turned out that the group of birds I shrugged off earlier as egrets were indeed white pelicans. They were just hunkered down low with their large sturdy bill swiveled around 180 degrees and resting on their backs. Even with binoculars, it was hard to distinguish these birds as pelicans due to their posturing to get under the wind.

We headed out on foot along an embankment that separated two of the impoundments in search of the birds. How elusive could they be? They’re 5 feet in length — from the tip of their tail feathers to the end of their bill — with a 9-foot wingspan, a huge orange bill and an all-white body except for coal-black wing tips. They should be easy to find.

Out on the water of the impoundments, tundra swans had already arrived for the winter. Their necks and heads submerged in the shallow water, they were searching for food. Nearby, coots and cormorants paddled about while great blue herons and great egrets stood statuesque along the edge of the shore. Then off in the distance, I saw about six white birds with black wing tips heading in our direction. This turned into a false alarm as a group of white ibis flew close enough overhead that we could hear the whistling of their beating wings.

As we moved on to the north side of the impoundment, I caught a glimpse of a small mammal running across the embankment and down into the impoundment. A river otter, I thought.

With the sun now casting long shadows, a golden glow settled like dew on the vegetation and water.

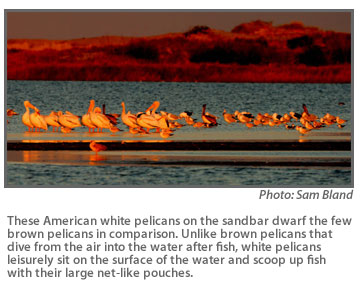

On the western horizon, a squadron of what looked like airplanes began dropping down towards the impoundment. There they were, about seven of these wayward birds landed on a sandbar in the middle of the impoundment, resplendent in the glorious light. In comparison, they dwarfed the few brown pelicans that were also on the sandy spit.

The white pelicans began preening their feathers to settle in for the night. As the curtain of darkness fell, the western horizon celebrated by releasing a canvas of red and orange streaks. In the marshy waters, a raccoon mimicked a boxer as it jabbed the water with upper cuts searching for prey, occasionally slipping a reward into its mouth.

As we walked out of the refuge, the soft cooing of the tundra swans echoing off the calming water held promise for the coming day.

Heading to Nags Head for the night, the silhouette of the Bodie Island Lighthouse stood out like a sentinel standing at attention. Its beacon, equaling the call of a siren, obligated us to stop. The rising moon, a day late of full, illuminated the structure as the beam flashed out its warning to mariners. A dark sky opposite the moon began popping out stars that danced about like a flame tethered to a wick. We captured, with our cameras, this stunning scene laid out before us, but the image, more importantly, will be forever etched in my memory.

The next morning, back out at the refuge, warmer temperatures invited mosquitoes to rise out of the shrub thickets to irritate me. I didn’t care because the white pelicans were more active and flying overhead between the two impoundments. At the far end of one of these wetlands a couple of them were on the surface of the water feeding.

Unlike brown pelicans that dive from the air into the water after fish, white pelicans leisurely sit on the surface of the water and scoop up fish with their large net-like pouches. In shallow water, they will work together to corral and direct fish into a concentrated area where the entire group can benefit. In deeper waters, where the reward isn’t as certain, they are mainly solitary feeders. They can’t be trusted by other water birds though, as they will not hesitate to steal fish if given the opportunity. This trait is known by biologist as kleptoparasitism.

We hiked down one of the embankments that offered a bit of cover to try to get a better look at the feeding pair. A young white-tailed deer leisurely walked the trail ahead of us, not one bit unnerved by our presence. At one point it actually turned and walked directly towards us before vanishing in the thicket-lined marsh.

Looking through the shrubs at the pelicans, I was able to appreciate the rareness of the sighting. I have seen them only a few times in my life. This time of year they should be wintering much farther south in the warmer climates of the Gulf Coast and beyond. During breeding and nesting season, they are typically found around the freshwater lakes, rivers and marshes of the northern Great Plains. Sightings are rare enough in North Carolina that occurrences aren’t even noted on range maps. However, each year wandering migrants are sighted along our coast and big lakes such as Mattamuskeet in Hyde County.

The two white pelicans were methodically dipping their bills and pouches into the water no different than ladles into a pot of soup. Their bill is the largest of any bird and the pouch is capable of holding two gallons of water. At the end of the bill is a short down curved dagger called a mandibular nail which is used for preening, snagging fish and personal defense. Before mating season, these birds grow a small horn-like appendage on the top of their upper bill. Known as the nuptial tubercle, the horn is thought to be a showy indicator related to courtship and mating since it drops off after the females lay their eggs. This seasonal growth is why the bird is also called the rough-billed pelican in some areas.

Alert to our presence, the two pelicans slowly and calmly peddled their webbed feet, propelling them out into the middle of the wetland. A small wake created by their breast plowing through the calm water etched a “V” on the glassy surface as they drifted away. The American white pelican is facing the same hazards to survival that plague other waterbirds. Loss of habitat, human disturbance of nesting sites and poor water quality all contribute to this species’ struggle for survival.

As we were hiking out, a few of the white pelicans awkwardly reached their enormous wings into the air and pulled themselves into the sky. Once in the air, their clumsiness turned into grace on the wing, leaving me to hope that we continue to see them for generations to come.

(This story is provided courtesy of Coastal Review Online, the coastal news and features service of the N.C. Coastal Federation. You can read other stories about the North Carolina coast at www.nccoast.org.)