Was ‘The Lost Colony’ really lost or just decamped to Hatteras Island?

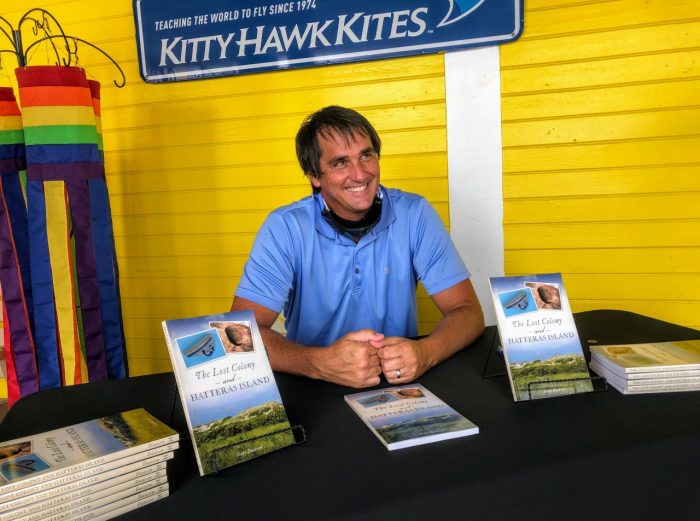

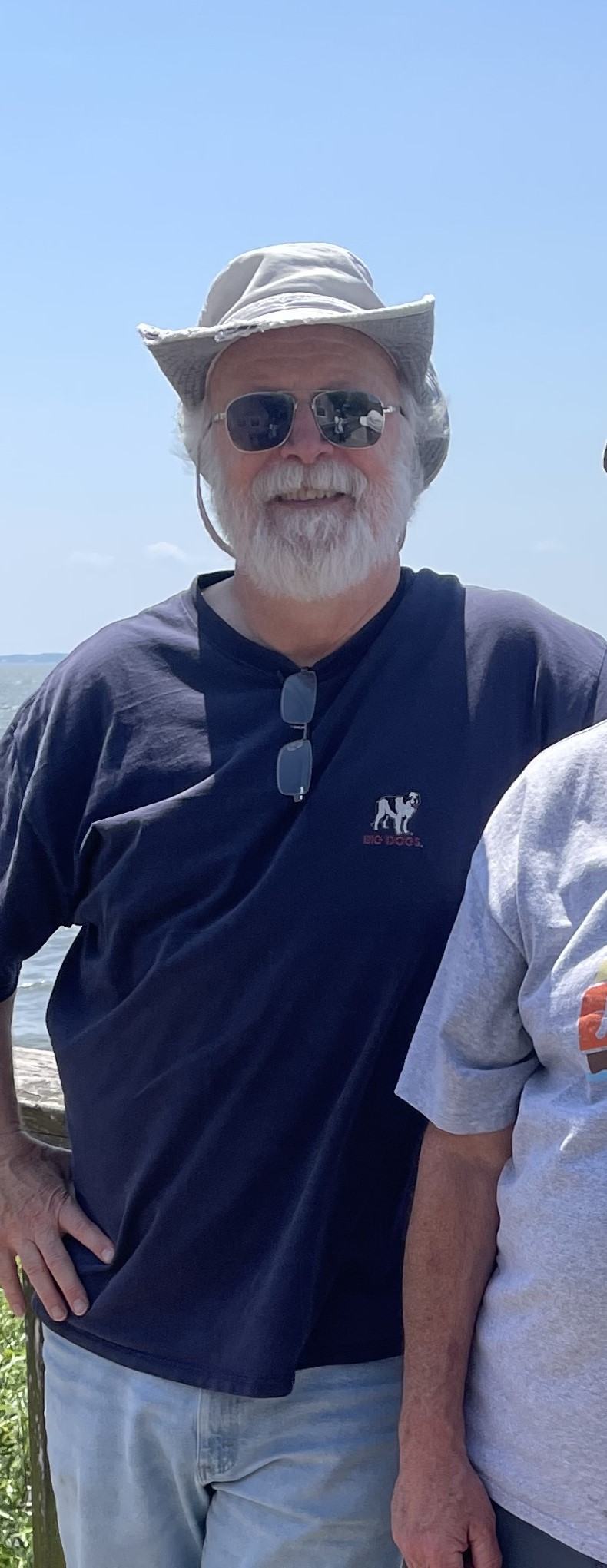

Scott Dawson is on a mission for the Lost Colony truth.

Scott Dawson is on a mission for the Lost Colony truth.

The native of Hatteras Island, or as he might prefer, Croatoan, has published a book that, among other things, debunks, he says, the myth of the Lost Colony.

The fate of the Lost Colony on Roanoke Island, Dare County, has been a matter of speculation, theories and debates since they disappeared after 1587.

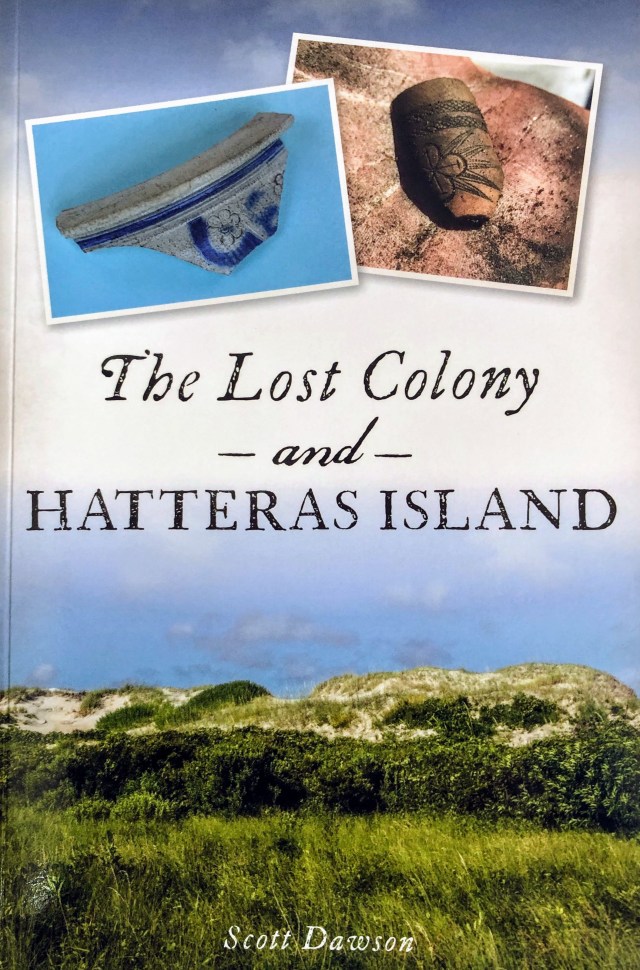

Through research and participating in hands-on archaeological digs around the Buxton area, Dawson is certain that the colony up and left Roanoke Island for Hatteras Island and presents this view in his book “The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island.”

Here’s a quick summary. In 1583, Sir Richard Grenville, a relative of Sir Walter Raleigh, organized four expeditions on orders from Queen Elizabeth I to establish a colony in North America. The first three voyages to the Outer Banks were of a military nature and consisted of only men.

The fourth trip in 1587 of 114 people, including women and children sent to set up a colony, landed on Roanoke Island, located near what is now Manteo.

Sir Walter Raleigh appointed John White as governor of the Roanoke colony. Among the colonists was White’s pregnant daughter, Eleanor White Dare, who gave birth to Virginia Dare, the first European born in the New World.

White made plans to return to England for more supplies and told the group that if they left to carve out the location where they were headed and, if they were in danger, to carve the cross symbol.

But just as he arrived in England, war broke out with Spain, and Queen Elizabeth I called on every available ship to confront the Spanish Armada.

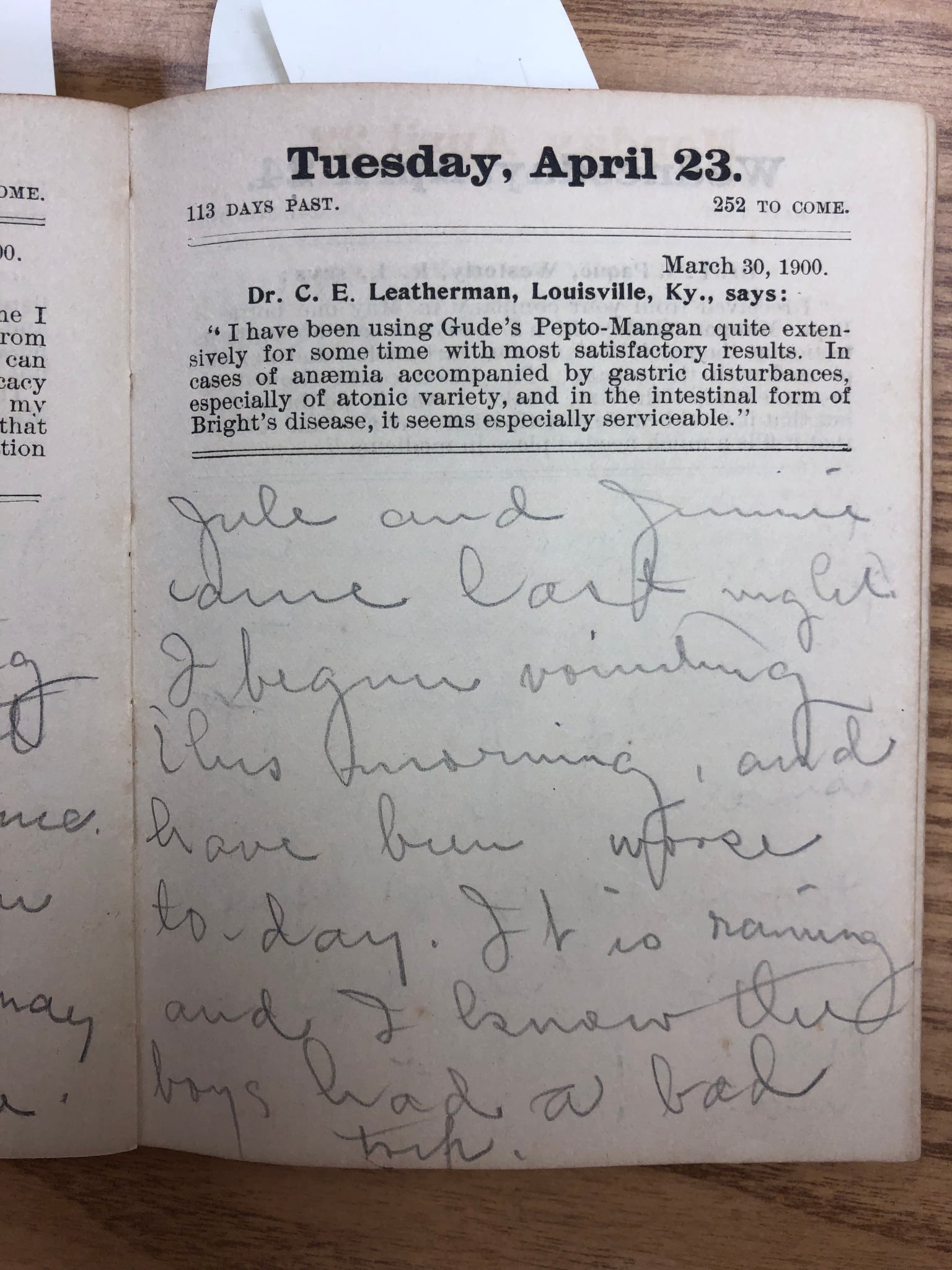

It took three years for White to finally return and he found the colony abandoned. Carved in a tree were the letters “CRO” and the word “Croatoan” carved into the fort’s palisade. That was the name for Hatteras Island back then. White intended to go to the island some 30 miles away to provide the supplies, but he never made it due to bad weather and a near mutiny. So, he returned to England.

“…in school, they told us that the word Croatoan is some mysterious word on a tree and no one knows what it means. I’m from Hatteras, and at least in that part of the world they never forgot what it meant, because it’s just the old name of the island.”

The story has intrigued Dawson since grade school. The more he read about it, the more convinced that the idea of a lost colony was a myth that has been perpetuated for many reasons, money being one of them.

“My interest in this history and archaeology was born out of frustration because in school, they didn’t really teach the lost colony story correctly at all,” he said in an interview. “And I knew, at least one part of it was massively wrong, because they told us that the word Croatoan is some mysterious word on a tree and no one knows what it means.

“And I knew that wasn’t true because I’m from Hatteras, and at least in that part of the world they never forgot what it meant, because it’s just the old name of the island.

“It doesn’t take but about two seconds of research to confirm that, and it’s labeled clearly on the maps from the 1580s. They even give the latitude to the inlets and if you keep doing research it’s mentioned over 1,000 times, and in 900 pages of documents, talking about the island, and the Indians who lived on it.”

In 2007, Dawson published “Croatoan: Birth Place of America” in which he postulated that it was at Croatoan that the English made their first contact with Native Americans. His new book is an update of what archaeological excavations have revealed since that earlier book.

Enter Mark Horton, a renowned archaeologist and professor at England’s Royal Agricultural University and Emeritus Professor at the University of Bristol.

“Dr. Horton was visiting (Roanoke’s) Festival Park because Manteo was doing a twinning ceremony with some little town in Ireland and another little town in England,” Dawson said, “and Mark got a hold of my book and visited.”

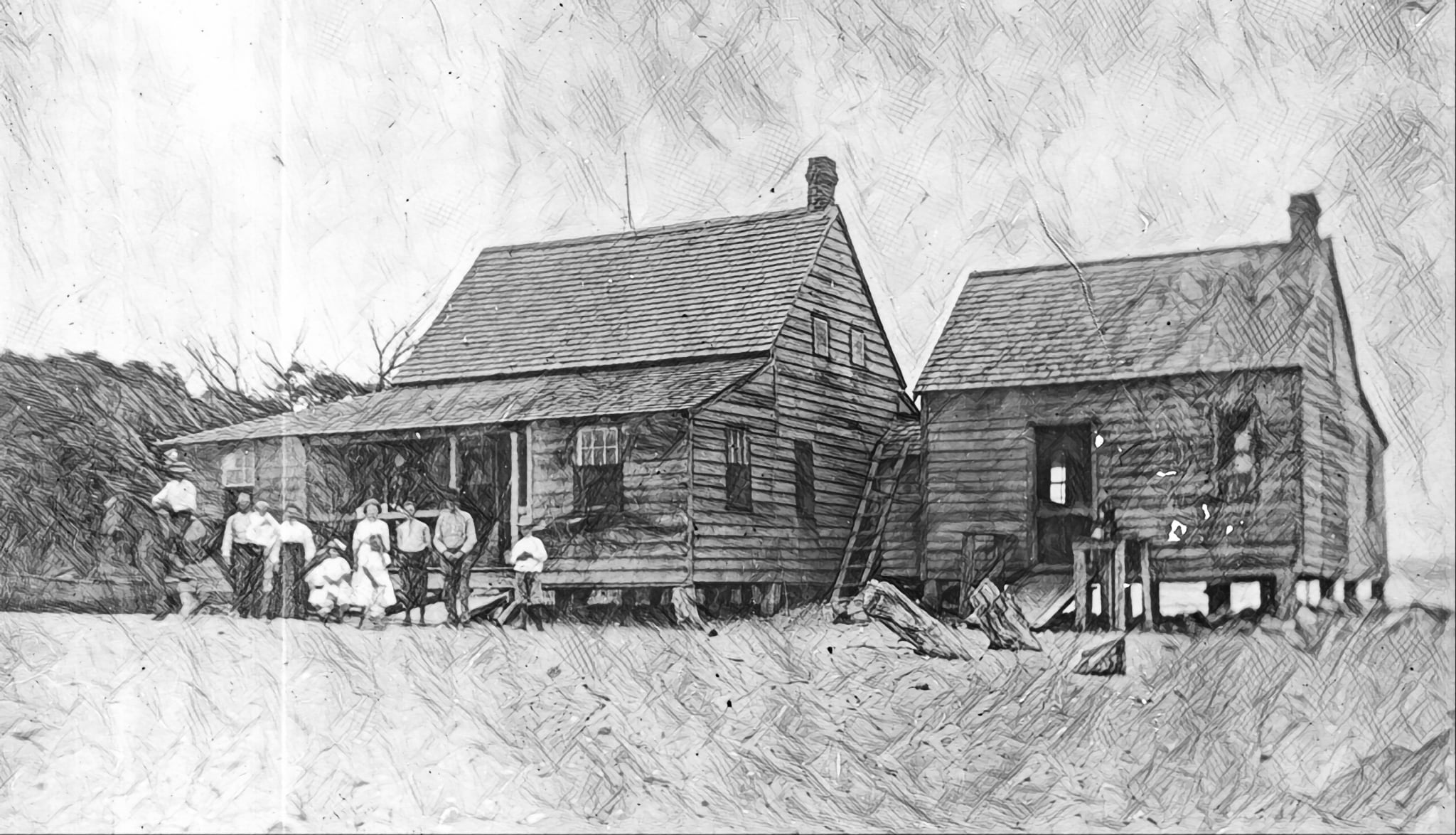

Horton was sufficiently intrigued with the artifacts he found while working with Dawson. So, Horton oversaw a series of digs from 2009 to 2018 conducted by graduate students from the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom and locals including Dawson and his wife Maggie Dawson, who co-founded the Croatoan Archeological Society.

Called The Croatoan Archeological Project, it unearthed a wealth of artifacts that added to the cumulative proof of the Native Americans on Hatteras island and their contact with the English.

Where the Roanoke colonialists went continues to be both debated and researched. Digs found in Bertie County have found evidence of colonialists present around the time of the late 16th century. Others have speculated that they headed north to the Chesapeake Bay area. Many think that the colony split up with some, but not all, going to Croatoan.

Dawson’s theory matches with that of Ocracoke Islander Ward Garrish, who requested his theory be published in the Ocracoke Observer shortly before his death in 2018. He studied Arthur Barlow’s 1584 “Report of Raleigh’s First Exploration of the American Coast,” along with original and current maps of the area and even created a map himself.

According to Garrish’s calculations, in Barlow’s account, Raleigh’s men would have arrived at Ocracoke Island, come through Old Nye Inlet (which no longer exists) and tied up at Woccocon (now Ocracoke Village).

His further research put the landing party just south of Buxton on Hatteras Island.

“I never met him (Garrish]), but I read about him and I like his theory,” Dawson said. “It’s the same thing I’ve been saying for 20 years.”

“The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island” is divided into two parts. The first is the history which includes information on the native American tribes, especially the Croatoan and the Secotan who were at war at the time the English arrived.

Dawson stresses the friendship between the English and Croatoan, who co-existed in peace on Hatteras/Croatoan island, even intermarried.

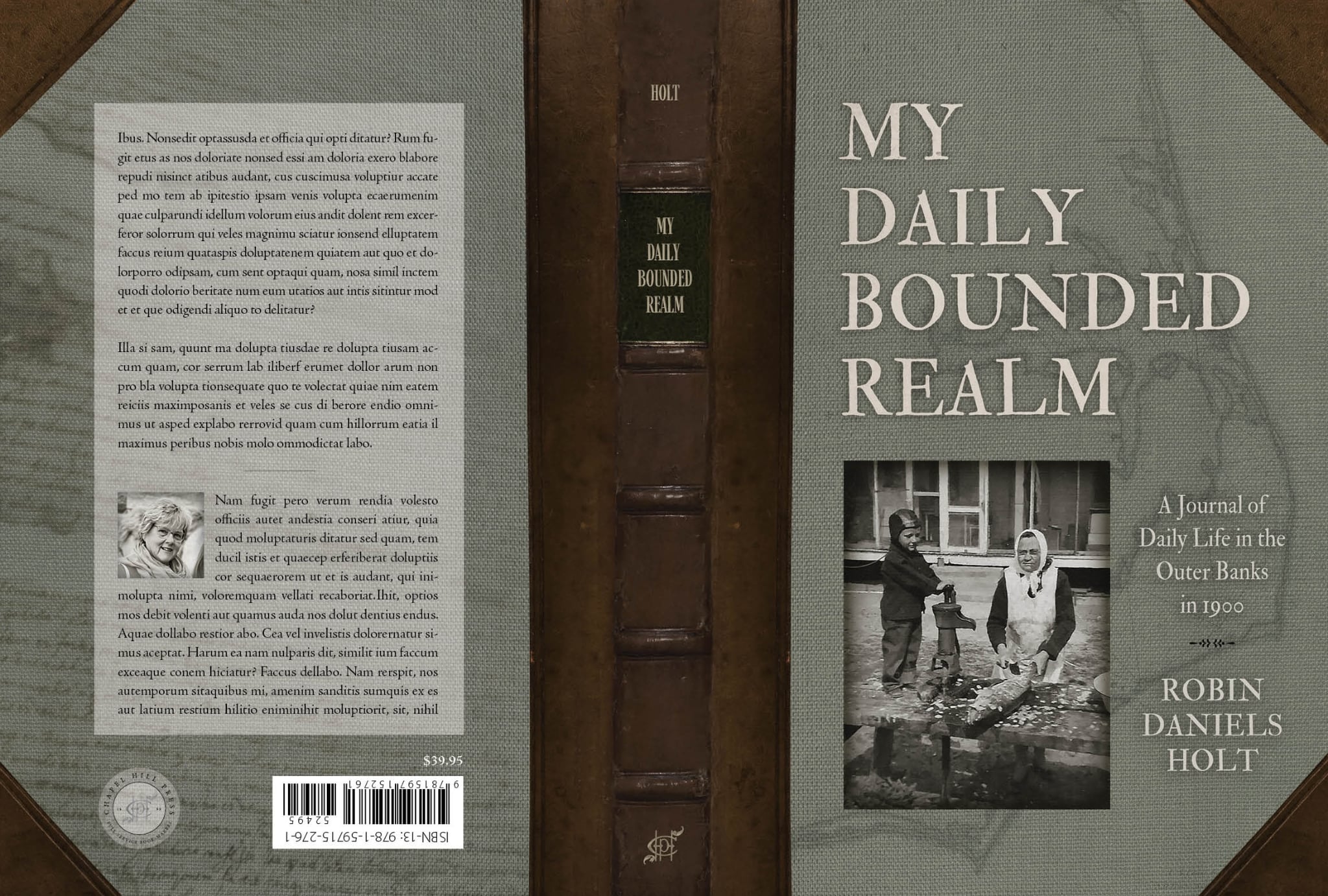

The second part, “Archaeology,” covers the many digs and discoveries found in the Buxton area over a period of 10 years and the meticulous, backbreaking yet exciting efforts needed in an excavation.

Dawson’s book is a good history/archeology primer. It is well-written and accessible for the lay reader.

The book is available at Books to be Red and other bookshops on the Outer Banks.