Scientist behind forecast tool warns of rip current dangers

While a dip in the ocean is one of the many joys of summer, beachgoers should be cautious of dangerous rip currents, which cause more than 100 deaths in the U.S. each year and 80% of lifeguard rescues, according to the U.S. Lifesaving Association.

Rip currents are the No. 1 public safety risk at the beach in the U.S. and worldwide, Dr. Greg Dusek, senior scientist for the Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, explained to Coastal Review.

“Rip currents are strong, narrow jets of water that originate near the shore, and then expand outward through the surf zone, away from shore,” Dusek said. “They’re caused by breaking waves. So anywhere where you have breaking waves near the coast, you can have rip currents.”

Rip currents are dangerous for several reasons including they pull swimmers — even the strongest — away from the shore, as well as rip current speeds can quickly increase and become dangerous to anyone entering the surf.

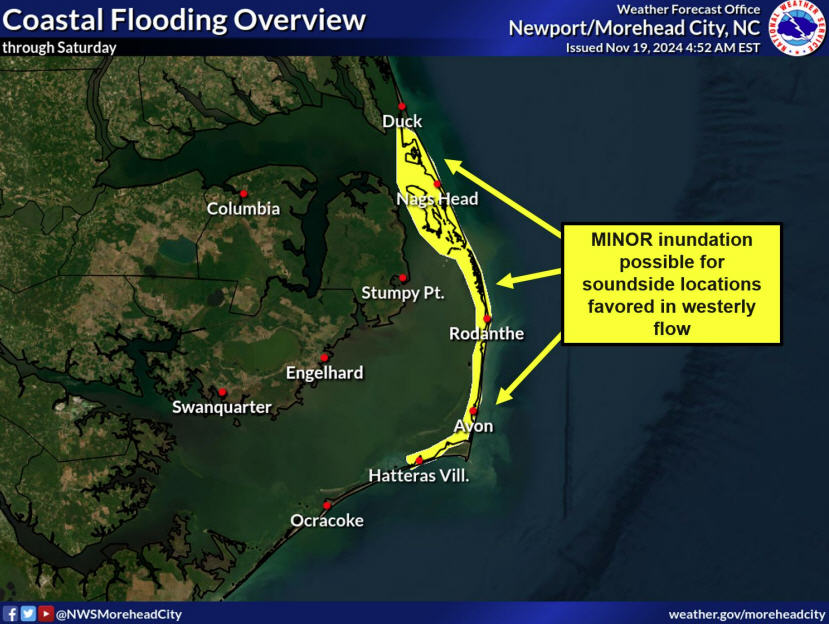

NOAA earlier this year announced what officials called a significant upgrade to the Nearshore Wave Prediction System, which provides on-demand, high-resolution nearshore wave model guidance to help inform the public about the hazards and chance of rip currents.

The model is the first hourly probabilistic hazardous rip current guidance that looks out six days ahead for the U.S. East and Gulf coasts, Puerto Rico, Hawaii and Guam. NOAA worked with the U.S. Lifesaving Association on the model.

Dusek, a graduate of University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, was behind the research of the new rip current model.

NOAA’s National Ocean Service and National Weather Service developed and implemented the model, which leverages wave and water level information from the recently upgraded National Weather Service’s Nearshore Wave Prediction System, according to NOAA. Similar to predicting weather or precipitation, the model predicts the likelihood of dangerous rip currents on a sliding scale from 0 to 100%.

Dusek said to find out beach hazard information for your coastline, visit https://www.weather.gov/beach/. For those interested in the computer model output, visit https://polar.ncep.noaa.gov/nwps/viewer.shtml, though this geared toward forecasters, emergency managers and such.

“We encourage the general public to always look at their local Weather Forecast Office page, which they can access through the beach page,” he said.

“Safety for beachgoers and boaters is taking a major leap forward with the launch of this new NOAA model,” said Nicole LeBoeuf, acting director of NOAA’s National Ocean Service, in a statement. “Extending forecasting capabilities for dangerous rip currents out to six days provides forecasters and local authorities greater time to inform residents about the presence of this deadly beach hazard, thereby saving lives and protecting communities.”

The initial idea to study rip currents began when Dusek was in graduate school in the late 2000s at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. He is now based in Maryland and grew up in upstate New York, but spent many vacations on the Outer Banks.

There’s been some form of rip current guidance dating back to the early to mid-1990s, but it was very simplistic daily guidance, he said.

For his dissertation, he studied rip currents to try to create a forecast model, working with Outer Banks lifeguards, the Army Corps of Engineers field research facility in Duck and the Coastal Studies Institute, now East Carolina University’s Outer Banks Campus, in Wanchese. Observations of waves, water levels, the shape of the ocean floor, and rip currents were collected. Lifeguards provided most of the observations of the rip current frequency and hazards.

“We used all that to create this model to predict the likelihood of hazardous rips going out six days in the future. And we’re able to provide that every hour,” Dusek said.

The model shows the probability, just like a precipitation forecast that predicts the possibility of rain. “That’s the same kind of idea with our rip current model, how likely is it to have a hazardous rip currents given what we know about the waves and the water levels.”

The initial effort was mostly focused in North Carolina when Dusek was beginning his research. Once he started working at NOAA and with the National Weather Service, the model scope expanded to include the entire United States. The different weather forecast offices, which are responsible for providing forecasts at different regions, also gave input and assessed the model.

Dusek noted that rip currents are hard to observe because you cannot put instruments in the surf zone, as they may not come back. Plus, rip currents are dynamic because they move in space and time. With traditional instrumentation, rip currents are really hard to measure, which is one of the reasons the model was based on visual observations. Also why lifeguards were such critical partners with the project.

“I think what we’re trying to do at NOAA — both with our modeling efforts and just communications more generally – is raise people’s awareness of how to identify rip currents, what kind of hazardous conditions there could be and then what to do if you actually get caught in a rip current to hopefully to be able to get out safely,” he said.

“What we see is that people get themselves in a hazardous situation and then can panic, which can lead to potentially drowning,” Dusek said. “I think a lot of people think rip currents pull you underwater, but they don’t. They just pull you away from shore. so as long as you can stay calm and float, you will be okay. The key is to not fight the current.”

Additionally, most people don’t realize how fast rip currents can travel. Rip currents can reach speeds of over 5 mph, “which I know people always think 5 mph, that doesn’t sound that fast, but that’s roughly the speed of a top Olympic swimmer. You can’t swim against that. So you have to stay calm float. And then you want to swim along the beach until you’re out of the current and then back to shore, following the breaking waves.”

Dusek said the best thing to do when you go to the beach is swim near a lifeguard because your chances of drowning next to a lifeguard are low. You can also ask the lifeguard if you’re unsure if the conditions are hazardous.

If there’s no lifeguard or you want to determine if there might be a rip current, Dusek said the best time to look is when you’re going over the dune line, or when you’re at an elevated position, because it’s much harder to see when you’re close to the water.

Rip currents are flattened spots in the line of breaking waves, or where waves aren’t breaking.

Many of his lifeguard colleagues shared with Dusek that people will go swim in the rip current because that’s where waves aren’t breaking and looks calmer, which he advises not to do.

You can also look for darker patches of water or foam, sediment and sand being pulled away from shore. “If you watch the ocean for a while you’ll kind of notice these features.”

He said he’s glad he has been able to continue research on this model well past his dissertation and is hopeful it’s used to save lives.

The probability model has relied on information about rip currents collected from lifeguards, but Dusek said they’re moving to using cameras, or webcams.

There is work on a project with Southeast Coastal Ocean Observing Regional Association, or SECOORA, University of North Carolina Wilmington, University of South Carolina and others on establishing a camera network throughout the southeast to provide video imagery for a whole host of things, including rip currents.