Island History: The 1876 fatal disaster mystery of the Nuova Ottavia

When the Italian vessel Nuova Ottavia wrecked on shoals off Currituck Beach just after sunset on Wednesday evening, March 1, 1876, it made no sense to any of the horror-struck witnesses, and the incident still makes no sense. It had been seen earlier about five miles from shore with rough seas and “rather high and heavy surf,” as reported at the time. Why did it wreck, and who would respond to these souls desperately in peril on the sea?

There are so many unanswered questions about this lengthy incident that it has become one of maritime history’s greatest mysteries, yet it does not have the fame of the “Ghost Ship” Carroll A. Deering or the Titanic. Nor the loss of the schooner Patriot, or the disappearance of Theodosia Burr, daughter of Aaron Burr, the third vice president of the United States. Her vessel simply disappeared off of Cape Hatteras in December of 1812 and she was never heard of again. However, many unlikely stories naturally evolved. We all want answers to mysteries.

But the fiasco of the wreck and attempted rescue of the Nuova Ottavia had many witnesses. A multitude of inexplicable mistakes were made. Why? What really happened?

A New Service for Shipwreck Victims

The predecessor of today’s U.S. Coast Guard was the United States Life-Saving Service. It officially began on August 14, 1848, with the signing of the Newell Act, initially sponsored by New Jersey Representative Dr. William A. Newell. Under this act, the United States Congress appropriated $10,000 to establish unmanned lifesaving stations along the New Jersey coast south of New York Harbor and to provide “surf boats, rockets, carronades and other necessary apparatus for the better preservation of life and property from shipwreck on the coast of New Jersey” (Newell Act). The name of this new and vital service, however, was misleading. At first, it only applied to unmanned stations on the New Jersey coast, and later similar stations were added to New York’s Long Island. This was because New York City was by far America’s most important and busiest port.

By June of 1876, when the Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for that year was released, these statistics were recorded for Districts 3 and 4, covering New York, Long Island for the years 1874 and 1875:

- Total Wrecks: 53

- Lives Saved: 360

- Lives Lost: 12

- Value of “property imperiled:” $1,093,595 (in 1875 is worth $27,951,095.19 today)

The lighthouses there were of no help in these cases. So, who can come to the actual rescue? By 1876, Long Island housed 28 United States Life-Saving Service stations and New Jersey had 38 for a total of 66, so it certainly was not a national service. Following a series of problems, the Service was reorganized and expanded in 1871, although still plagued by cronyism, but beginning to become national.

The Attempted Rescue

From the original source: “The bark Nuova Ottavia was seen from the station – house at sunset to the southward and eastward, about five miles distant from the shore, on the evening of March 1, the weather being cloudy and the wind from southeast, the sea rather rough and the surf rather high, heavy, and winding. Between 7 and 8 p. m., or soon after dark, she stranded on the reef [meaning sandbar].” (Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the fiscal year ending June 30,1876.)

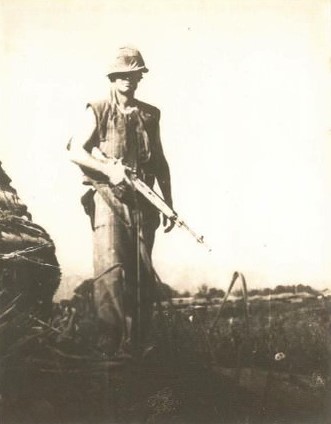

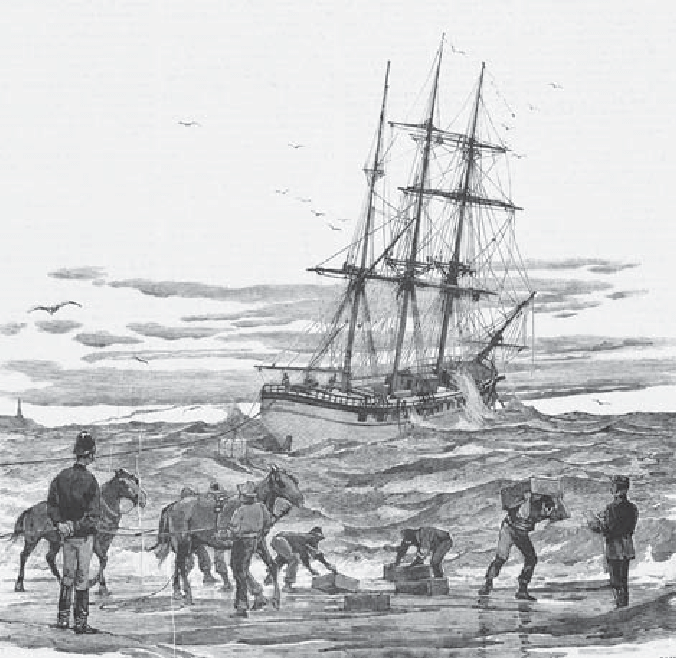

The crew of the United States Life-Saving Station No. 4, Jones Hill, responded immediately. This station was a mile north of the new Currituck Beach Lighthouse, which started construction in 1873 but was still undergoing finishing touches by a team of workers. Although dark by 7:20 p.m., and although the vessel lay only 400 yards offshore – an easy and safer rescue via the breeches buoy or lifecar with the Lyle gun – instead, the Keeper and crew launched the surfboat. This was yet another major mystery, and it was compounded by the omission of all the surfmen donning the only safety device they had – cork life vests.

The crew and the keeper were inexperienced, since the station had only been established two years earlier. Still, they launched their rescue craft. The crowd of locals and lighthouse workers that soon gathered on the beach watched the surfboat successfully negotiate the initial crashing breakers, the single hardest part of the launch. They watched the small lantern light at the rear of the boat bob up and down as it was battered by the rough surf until it went out of sight. Suddenly, a terrifying screech and scream was loudly heard back on the beach. Then silence.

Shortly thereafter, the stunned crowd that had gathered on the beach kept watch. They were shocked to see one of the surfboat’s oars drift ashore. Then a second one, then a third, and finally a fourth. Then the boat itself appeared as a ghost, bottom turned up. The answer to the terrifying question on everyone’s lips was answered when the body of Surfman Malachi Burmsey floated in on the surf.

The nightmare unfolded as one by one the bodies of Keeper Gale, Surfman Lemuel Griggs, Lewis White, Spencer D. Gray, and volunteer George Wilson, as well as five unidentified Italian sailors, washed ashore. By 2:00 p.m. the next day, the Nuova Ottavia had been battered by the brutal surf into so many pieces that she simply disappeared. One large section of the stern had come ashore near Kitty Hawk, 20 miles farther south.

The Tragedy and the Mystery

Incredibly, this was the first loss of life by any surfman in the United States Life-Saving Service anywhere in the nation. Worst still, it was the loss of the entire crew of the 1876 Jones Hill U. S. Life-Saving Service Station No. 4.

By 1876, there were 108 United States Life-Saving Service stations on the Atlantic Coast alone from Maine to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Another seventeen stations existed in Florida, the Great Lakes, and the Pacific coast. Since each were staffed by six surfmen and one keeper, the total LSS personnel in 1876 totaled 875. That year, the Annual Report tells us, there had been 108 shipwrecks which surfmen had responded to, usually in the direst of circumstances. Yet not one surfman was lost in the line of duty – until Jones Hill, Outer Banks, North Carolina, 1876.

Speculation

New Lighthouse, Old Charts

A plausible argument is initially expressed in the Service itself: “(vessel) having probably been run ashore either intentionally or through mistaking Currituck Beach light for the Cape Henry light, as it evidently was not from stress of weather, quite a number of her sails being left standing, not even clewed up, all night, and went over the side in this condition with the mast the next day.” Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the fiscal year ending June 30,1876, p. 12. This is total conjecture, however, since the captain was drowned. No witness testified that this is what happened to cause the wreck.

My great friend and colleague, Meghan Agresto, Currituck Beach Lighthouse Site Manager & Historian, came across an interesting piece of information and quoted this in an article, “Being unacquainted with the coast and unable to see the sun that day to take their observations, they mistook the Currituck light-house for the light at Cape Henry, and were on the proper course to clear it under that supposition; but they soon found out that they had miscalculated their locality and were in peril of their lives. The mate says the lighthouse, which is new, is not down on the old charts by which they were sailing.” Most unfortunately, that was from a newspaper article from Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1876, p.1. This was during a period when newspapers were notorious for inaccurate, sensational ‘reporting’ that often was entirely or largely fictitious.

There was an official investigation of the Nuova Ottavia wreck afterwards. The records show the sole testimony given by the four surviving Italian crew members described what happened when the life-saving station surfboat reached their wreck. There was no information about why the vessel wrecked. So, while we can make guesses, we still have zero direct facts from the original sources. That is why it remains a mystery, so far. The aformentioned ‘mate’s’ statement was apparently part of this fictitious newspaper report. It is nowhere in the official records, and certainly would have been if true.

Suspect Leadership

In 1876, the Life-Saving Stations were only operational for several months, which they called “the storm season” or the “active season.” Those dates varied by the District, due to climates and meteorology. The Active Season for District 6 (VA and NC) was December 1 through April 1. The 1874 Jones Hill station and crew had only been operational for a maximum of four months – December, January, February and March – in each year. This was therefore only the third short month season that the Jones Hill station had been in operation.

The entire Life-Saving Station crew were locals. At best, they would have only had 10 months of training and experience by March 1, 1876 (1874: 3 months, opened Jan-Mar) 1875: 4 months (Dec-Apr 1), and 1876: 3 months (Dec – March 1).

Following the wreck and bungled rescue, there was an unusual turnover of station keepers. John R. Gale was appointed on Dec 11, 1874 and left the service in 1876. John G. Chappell was appointed on Mar 18, 1876 and left the service in 1877. Daniel M. Etheridge was appointed on Dec 30, 1879 and was discharged on MAR 31, 1888. Without further investigation, this is also somewhat mysterious.

Only Survivors

The singular statement from the four Italian crewmen was in the official report: “The superintendent subsequently furnished the following additional facts obtained from the survivors of the bark: The boat [station’s surfboat] pulled entirely around the vessel [bark Nuova Ottavia] when she first went off, and finally secured a line on the lee side. Holding on this line with a considerable scope brought the boat under the bows of the bark where the sea was curling around, which partially rebounding, filled her.” (p.13)

Nearly A Century and a Half Later

March 1, 2022, marked the 146th anniversary of this sad, mysterious event. A series of unanswered questions that became the mystery are still not explained to this day:

- Why and how had the Nuova Ottavia wrecked and grounded where it did?

- Why did it keep its sails up after running aground?

- Why did she keep them up all night?

- What were the qualifications and conditions of the Italian captain and crew?

- Did Jones Hill LSS Station Keeper Gale notify his neighboring stations?

- Why was the Lyle gun not used?

- Did the Keeper and crew not have enough training to use it?

- Why were the cork life vests not used?

- Why was the lifecar not used?

A Little Good News

Near the end of the Annual Report, it stated, “During all these events Mr. J. W. Lewis, superintendent of construction, and Mr. H. T. Halstead, clerk of the Currituck Beach light – house station, were constant and assiduous in their efforts to render all possible aid, and too much praise cannot be awarded them …. The officers and working party of the light – house rendered most useful assistance, and worked night and day, and it is hoped their services will be recognized in some official manner.”

Agresto found a detailed apology of Lot Morrill, the Secretary of Treasury at the time, for not recognizing the brave crew at the Currituck Beach Lighthouse sooner:

“The department deeply regrets that through inadvertence the noble conduct of the officers and men of the working party at the lighthouse has not received due official recognition, and desires now to express through you to Messrs. Lewis and Halstead, and to their associates, whose name are not known, its profound sense of their manly behavior, and the value of their self-denying labors upon the occasion referred to, sadly including in its appreciation their gallant comrade, George W. Wilson, who honorably died in the endeavor to save human life. LOT M. MORRILL Secretary of the Treasury. The names of the employees at the lighthouse station referred to in Secretary Morrill’s letter as having rendered valuable assistance are as follows: Henry L. Tebbets, S. Bowers, L. H. Alton, John W. Cooper, Bennett R. Lawson, Wm. T. Kemp, George Clarke, George I Sauner, Wm. Wallace, Paul Leonard, W.C. Horner, V. M. Capps, Mesick O. Travers, Walter A. Travers, Henry Hubbard, John S. Dunlevy, A.N. Hurdle, Edmund Spry, Banister Hewell, and Henry Miner.”

To Be Continued…

Linda Molloy is not only my wife, but also my in-house editor, historian colleague, brain-storming partner, researcher and idea-generator. As we continued the pursuit of this mystery, we discovered a door through which we might have the answers. Surely, we were not the first to encounter this portal, but we could not see that no one else had been through it. So, just like the determined adventurers who have been digging the Money Pit on Oak Island, we also will continue to dig into these depths to discover the answers to the mystery of the Nuova Ottavia – which will be our treasure!

The more detailed story is only one of the 24 chapters in Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks: Dramatic Rescues and Fantastic Wrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic, Globe Pequot Press (imprint of Rowman & Littlefield), ISBN 978-1-4930-3590-8 (Hardcover).