How the OBX Repeater Association carries on Fessenden’s legacy

By Maggie Miles

Local ham operators remain a key resource in emergency events

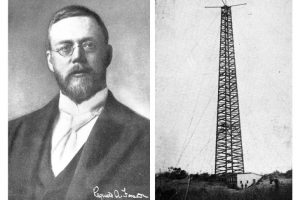

In 1901-1902, while the Wright Brothers were conducting their history-making experiments in flight, Reginald Fessenden, a Canadian physicist, was conducting lesser-known, but equally groundbreaking work just a stone’s throw away on Roanoke Island.

Coined the “Father of Radio,” Fessenden erected 50-foot-tall radio towers at Weir Point on Roanoke Island, Cape Hatteras, and Cape Henry during those years, according to the National Park Service bio of the “Radio Pioneer.” And in March 1902, he successfully transmitted and received a 127-word voice message from a tower on Cape Hatteras to a tower in Roanoke Island—laying the foundation for modern radio and paving the way for technology like sonar and mobile phones.

In places like the Outer Banks, it was also the only way to communicate with ships out at sea. And today, this type of voice radio, now called amateur or ham radio, is still seen as the most reliable form of communication, with infrastructure that can withstand extreme conditions when the internet and cell towers can’t—making ham radio operators vital in events such as natural disasters, severe weather events, and other emergencies.

According to Greg Akers, President of the Outer Banks Repeater Association (OBRA), that is just what their association has been doing for the Outer Banks for half a century. “And you could argue that virtually everything we do now has some basis on what [Fessenden] did back then,” notes Akers.

The Outer Banks Repeater Association is a 501(c)3 non-profit aiding communication for emergencies and other events in Dare County. With their operators, they help Dare County Emergency Management in times of crisis, aid at athletic events of all kinds, and provide communications as needed to the public and government agencies.

On June 24 and 25, members of the association will be set up with a transmitting station at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site as part of Radio Field Day to demonstrate ham radio’s science, skill, and service to the community. Radio Field Day is ham radio’s open house. Every June, more than 40,000 “hams” throughout North America participate in the event. Field Day has been an annual event since 1933. It remains the most popular event in ham radio—with members at the event conversing with other ham radio operators worldwide.

According to Akers, it’s referred to as amateur radio because the FCC doesn’t allow people to profit off using these radio communications—so any services ham radio operators provide are volunteer-based. “Amateur Radio allows citizens the right to transmit voice over radio waves that are generally viewed as being restricted by the FCC in the United States,” said Akers.

The volunteers are permitted to do this by attaining their license, which includes going through an examination process that the FCC ordains. According to Akers, there are three different levels of licensing, and the Outer Banks Repeater Association helps anyone interested in working through the licensing process. Many of the volunteer members are retirees or former military with some kind of tech background, but there are some women and teenagers as well.

“The purpose of this is so we can talk,” said Akers, adding that his wife jokes that ham radio operators are just a bunch of old men talking about the weather.

OBRA is part of a network of clubs governed by an organization called the Amateur Radio Relay League (ARRL) that all serve a similar purpose in their communities. According to Akers, OBRA works closely with the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in Manteo— so closely that when there is a hurricane or emergency situation, some members go to the Emergency Operations Center and live there with the first responders. They operate radios there to provide reports to the Emergency Operations Center and information about what the OBRA operators out in the field are seeing.

“So let’s take an example,” explained Akers. “There was a period of time during one of the last storms when I was actually operating in the EOC. And someone called in and said that the road on [NC] 12, down south, was impassable. And we were able to get information to tell police, fire and NCDOT what the situation was before they could get people on-site because our operators happened to live in the areas,” Akers tells the Voice.

He recalled another time last year when everything south of Rodanthe got cut off from internet and phone service because a cable was accidentally cut. During that period of time, there was no phone, there was no Internet, there was no cable and no audio systems for police, fire and EMS.

“So we were able to use our communications to talk to people down there to find out what they need, and what they might require, and help them get information about what was going on,” Akers noted.

According to Akers, OBRA also installs equipment in all of the regional fire stations. In many cases, they have licensed amateur operators that are volunteer or staff firefighters that can operate that gear. But the association maintains it, makes sure it functions, and gets it tested every year.

OBRA is also set up at stations at most major sporting events on the Outer Banks, including half marathons, marathons, triathlons, and fishing tournaments in places where cell phones won’t work in case of an emergency occurs with any of the participants.

“We prepare ourselves to communicate in both of those situations by doing things like rehearsing drills, and we check our gear out once a week together on a Thursday night network, as we call it. That’s a place where everybody comes together and talks for about an hour. And then in the case of storms, we actually do hurricane preparedness drills and training so that people can know how to operate during hurricanes,” Akers added.

OBRA has a communications system they own that is a series of repeaters—hence the name. Repeaters are specialized radios that listen on one channel and transmit more broadly to other channels so that they can extend the reach of the radios beyond what radios normally can operate at. Akers explains that police and emergency services signals are typically attached to telephone poles.

“Our system is all based on towers,” says Akers, adding that, they share towers with those using them for other purposes—such as one tower used by the Navy and Coast Guard, and a few being used as radio towers. These towers are stronger and taller “so our system is a little less susceptible to being taken out by high wind and heavy rain and things like that.”

And if you are curious about what happens when you are on a tiny remote strip of sand during a worldwide catastrophe, OBRA could become the link to the outside world.

“If the Outer Banks were to be completely isolated, and there was no other way to communicate outside of the Outer Banks, you know, think about a catastrophic event that took out all communications, we could actually…communicate with people all across the world,” Akers explained.

He tells the Voice that the Outer Banks is a popular place for operators around the world to try and contact. Why is it hot spot with for hams?

“Because it’s unique,” declared Akers. He added that Fessenden chose to do his work on the Outer Banks because of the openness of the flat contour of the land that did not impede radio waves. He also proved that it was easy to communicate via radio over salt water, sending out the first transcontinental voice transmission to the UK in 1906.

The Outer Banks’s place in radio history “is very significant,” Akers observed. “And that’s we have a lot of operators here that are people that care about that history.”

For more history on Reginal Fessenden watch the Outer Banks History Center and Current TV’s

“This Month In Outer Banks History – Reginald Fessenden”