Dolan, Godfrey: Scientists proved Outer Banks are moving

by

This historical profile is presented as part of Coastal Review’s 2024 yearlong examination of 50 years of the North Carolina Coastal Area Management Act, including the science that helped to inform and the advocacy and leadership that resulted in passage of the landmark 1974 legislation, as well as the coastal environmental challenges yet ahead.

Robert Dolan and Paul Godfrey didn’t meet the way scientists often do, at a conference or sharing a drink after a long, technical talk. Instead, they met on a wind-blown beach near Cape Lookout, part of the long, winding bands of sand we know as the Outer Banks. It was 1971.

Godfrey, a quiet but creative botanist, and his wife Melinda, a pathbreaking marine biologist, had been digging cores along transects in the sand and mud for a research project trying to determine the history of the remote, 28,000-acre Cape Lookout National Seashore. Each layer of sand, peat and mud was like a chapter in a book, they recalled, secrets revealed here, surprises there, building to an unexpected ending.

Dolan, a coastal geologist who specialized in sedimentology, was also digging cores, near Cape Hatteras. He had arrived there almost on a lark in 1959 searching for a topic for his doctoral dissertation. “Why not study the Outer Banks?” one of his professors at Louisiana State University suggested. At the time, little was known about the chain of islands’ geology; some scientists even theorized the Outer Banks must be anchored to a coral reef, which prevented the islands from washing away. Ever confident and always up for an adventure, Dolan packed the family wagon, collected his wife and young daughter, and off they went. A decade later, he was still studying the islands and publishing seminal papers when it was suggested he meet Paul Godfrey and his wife, who were doing similarly impressive work a couple of hours away by boat on the undeveloped Core Banks.

Dolan and Godfrey knew one another from their work and contacts in the National Park Service, which manages the seashores. But they had never spoken, let alone met. Paul and Melinda took Dolan and several park service officials to see their cores, which Melinda had cleverly engineered with PVC piping.

Paul Godfrey, now 83, and living on a nature preserve in Western Massachusetts, recently recalled: “I think Bob was really intrigued. All of the species we identified as being adapted to the coast, he picked up on that right away. He saw we were coming to similar conclusions. The islands weren’t fixed in place like people thought. Nor were they washing away. They were fine, healthy, moving and adapting, the same way humans do.”

“The islands weren’t fixed in place like people thought. Nor were they washing away. They were fine, healthy, moving and adapting, the same way humans do.”

— Paul Godfrey

After their meeting, Dolan and Godfrey began to work together on various projects while they consulted for the park service and held down jobs as young professors at the University of Virginia and the University of Massachusetts, respectively.

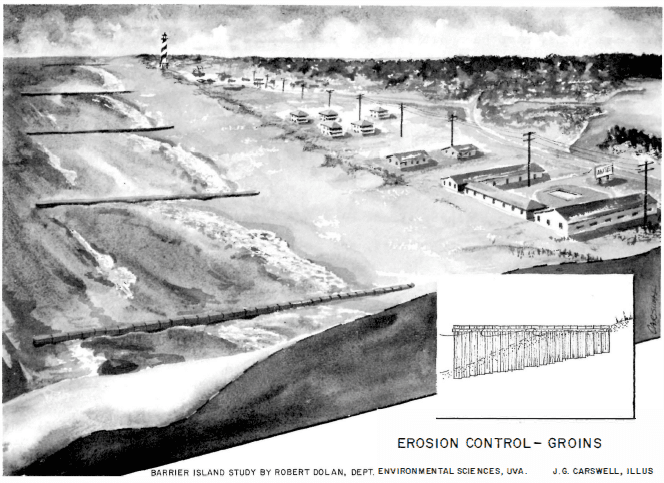

Their collaborations would forever change the way coastal scientists looked at barrier islands and prompt the National Park Service to reverse its decades-old policy of trying to hold the islands in place by constructing artificial sand dunes, engineering the beach, bulldozing sand around after storms, even fertilizing the grass and shrubs by plane.

It all sounds so simple today — allow water, wind and storms to naturally sculpt the islands — but it was a revolutionary idea in the early 1970s, even heretical. Many villagers had grown accustomed to the park service protecting them and keeping open N.C. Highway 12, the only route on and off the islands. Even today, decades later, the politics are challenging, with the park service expected to provide a buffer between the ocean and the ever-larger and more expensive vacation homes that line the eroding shoreline and fuel the Banks’ billion-dollar tourism economy.

They made an unlikely pair. Robert Dolan grew up in Southern California and was an avid surfer and self-described beach bum at a time when surfing was considered novel and daring in the Golden State. Following a stint in the Navy, he earned undergraduate and master’s degrees in the Earth sciences at Oregon State University. He then headed south, to Baton Rouge, to work on his doctorate in coastal geology at Louisiana State University. Various profiles of Dolan, including one in John Alexander’s 1992 book, “Ribbon of Sand,” described him as confident, exuberant, passionate and adventurous.

Paul Godfrey grew up on a small farm in central Connecticut where he developed an abiding respect for nature. Melinda: around water on Cape Cod, where she learned how to handle boats and measure her own confidence in a world dominated by men. The future couple met in graduate school at Duke University, where Paul was pursuing a PhD, Melinda a master’s. One day, Melinda walked into a call on soil composition affectionately called “Dirt.”

“It was all men,” Paul recalled. “Melinda walked in and all these men were saying, ‘What is she doing here?’” They became lab partners and later Paul followed Melinda to Beaufort, where she worked as an assistant in the school’s renowned marine lab. “It was how I got interested in the coast. Melinda taught me. She was pretty, too,” he laughed.

After arriving on the Outer Banks, Dolan settled his wife and young daughter in a Nags Head cottage about 200 yards from the Atlantic Ocean. In the early morning of March 7, 1962, Dolan awoke to find the ocean rushing under their cottage. Another cottage, seaward of his own, had broken loose and was crashing toward them.

“In record time, I packed my personal belongings and research gear into a four-wheel-drive vehicle and headed for high ground,” he wrote 25 years later in an editorial for the Journal of Coastal Research.

Dolan had wanted to study the effects of powerful storms on barrier islands. Here was his chance. After delivering his wife and daughter to higher ground, he returned to take measure of the damage. The Ash Wednesday Storm, a three-day nor’easter featuring five high tides, each one higher than the last, was one of the strongest storms to ever strike the Outer Banks. It flooded or flattened scores of homes, crumpled a pier where Dolan had recently installed a tidal gage, and washed away a 30-foot aluminum tower he had built to take photos of the beach.

But the storm also answered some of his research questions. For example, it showed that the massive artificial dunes that Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps workers had constructed during the Great Depression to “stabilize” the islands were no match for the storm surge and waves. It also demonstrated how the storm washed large fans of sand across the road to the middle of the island, elevating it, a form of coastal adaptation now known as overwash. As long as man didn’t interfere, barrier islands would heal themselves even after epochal storms, Dolan concluded, shifting sand inland, slowly rebuilding foredunes, widening the marsh along the tidal inlets and sounds.

Dolan had also used a machine to dig 140 cores to study sand samples and test the theory that the islands were anchored to coral reefs. He dug and dug. But all he found was sand, layer after layer, one older than the last — a clear indication that the islands weren’t fixed in place, but were moving. Always moving.

Paul and Melinda Godfrey arrived at similar conclusions near Cape Lookout. Melinda had ingeniously found a way to use PVC piping to take deep samples of sand and mud. She and Paul then pored over each layer, studying the shells, clams and plants for hints that helped to date the formation of the island. The wider and deeper they dug, the more surprises they found: snails near the beach that only could have come from the marsh; shells near the marsh that only could have come from the beach. It was their eureka moment, “powerfully proving,” Godfrey said, “that the islands were moving, slowly rolling over themselves as they inched their way toward land.”

Dolan had begun writing up his findings in research papers for the National Park Service while becoming increasingly vocal about the threats that rampant development posed to Cape Hatteras National Seashore. In 1972, he was joined by Paul Godfrey in a paper questioning the park service’s decades-old practice of spending millions of dollars on dune-building and beach-engineering after storms. The service’s practices gave “the false impression of safety and stability offered by the [artificial] barrier dunes,” they wrote. “As the system is stabilized, man builds roads and utilities that establish a `line-of-development’ which soon becomes a ‘line-of-defense.’”

As you might imagine, the criticism made for some tense moments between the researchers and the park service. “But to their credit, they came around,” said Godfrey. In 1973, Director Ronald H. Walker announced that the park service would no longer try to hold the line against the forces of nature. “There is just no way the National Park Service can continue to fight nature,” he told reporters. “We’ve spent all of this money; tried various ways to control the situation, but none of them has worked.”

“There is just no way the National Park Service can continue to fight nature. We’ve spent all of this money; tried various ways to control the situation, but none of them has worked.”

— Ronald H. Walker, Director, National Park Service, in 1973

The policy shift was the direct result of the work of Dolan, who died in 2016, and Paul and Melinda Godfrey showing that the Outer Banks were “dynamic natural landscapes” that will adapt and repair themselves after storms, losing sand in some places but gaining it in others as part of the natural evolutionary process of barrier islands.

Despite their warnings, developers and governments continued to add thousands of vacation houses and investment properties along the shifting shorelines – scores of which quickly were threatened by rising seas and storms. In the last few decades alone, county, state and federal taxpayers have spent tens of millions of dollars renourishing beaches, building and rebuilding artificial dunes, and constructing multimillion-dollar bridges to bypass storm-damaged roads.

In 2021, the park service adopted a revised sand management policy to help speed up the permitting process, allowing state workers to repair dunes and scrape sand off of N.C. 12 and other applicants to seek sand management permits within national seashore boundaries. But even that may not be enough to satisfy property owners and politicians.

Recently, U.S. Rep. Greg Murphy, a Republican representing North Carolina’s 3rd District, drafted language directing Cape Hatteras National Seashore Superintendent Dave Hallac “to identify potential long-term, cost-effective sediment management activities to minimize the impacts of beach erosion.”

The spending bill provision and ever-evolving policy could place the National Park Service back in the beach-building business.

Footnote: Dolan and the Godfreys continued to study the Outer Banks for decades, bringing hundreds of eager students to dig cores, study the ecology and geology, and experience the unfiltered beauty of the Banks.