Island History: A spotlight on stories from the Outer Banks’ Life-Saving Service

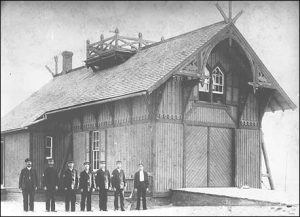

The Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station (CLSS) is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year, as one of the seven original Life-Saving Stations to be built in North Carolina in 1874.

As such, the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station and Historic Site in Rodanthe will be sharing stories about the seven 1874 Outer Banks stations in the months ahead, leading up to the official October celebration of the United States Life-Saving Stations’ 150th anniversary in the state.

The following is the next of these Life-Saving Station feature articles to honor the #LegacyofLifeSaving, written by Jen Carlson for CLSS.

All in a Day’s Work – Helping neighbors at Little Kinnakeet Station

Sometimes it’s just about being a good neighbor. On November 16, 1884, the small schooner, Adamant, broke loose from her anchor and was driven ashore in a heavy blow just south of the Little Kinnakeet station, which is located north of present-day Avon.

The vessel’s crew of three lived locally and were onshore at the time of the incident. For almost a week, she remained on land before the captain of the vessel requested help from the Little Kinnakeet Life-Saving station crew to get her back into the water.

As a result, the crew dug her out of the sand and used rollers to move the vessel about 40 yards. Soon, the Adamant was floating once again, with no injuries or major damage during the incident.

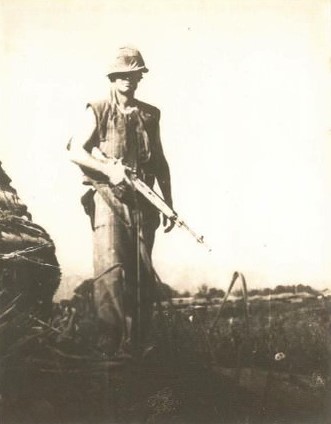

Unwavering Courage – A spotlight on a milestone moment in Life-Saving Service History

In the wee hours of November 24, 1877, the steamer, Huron, stranded itself about two and a half miles from the Nags Head Life-Saving Station.

Rough seas caused the vessel to keel over so her crew valiantly tried to survive the storm by clinging to her remains. Unfortunately, the Nags Head station wasn’t open for the season, so no assistance was coming from shore. Ensign Lucien Young and Seamen Antoine Williams undertook the hazardous challenge of attempting to get a line from the vessel to shore in the hopes of helping their comrades make it to safety.

The two men worked together to untie the balsa, a small rubber raft, which had become entangled under the starboard bow.

After freeing the balsa, the two men attempted to row to shore, but the rough waves promptly flipped them out into the water. Unshaken, the men gained a handhold on the raft and began swimming it to land.

Four times, the water capsized the small raft and attempted to drown the determined men, and four times, they recovered and kept swimming toward safety.

Finally, they reached the surf, exhausted from their arduous swim. Turning, they saw two fellow comrades struggling in the breakers so Young and Williams headed back into the water to pull the two men ashore.

After reaching shore a second time, they realized the balsa was being tossed into the surf, so yet again, they went back into the water to retrieve the small boat in hopes of using it as a life car. Unfortunately, the line was too short to reach the stricken vessel, so now they had to find a line long enough to reach. Spotting two more seamen in the breakers, Young and Williams entered the rough water a third time with locked hands in order to drag the men to safety. Seeing no one else in the breakers, Seamen Williams tended to the exhausted men while Ensign Young headed to the nearest station trying to find a long enough line. Finding the Nags Head station closed, Young broke in through the front door to retrieve equipment he could use to help his fellow seamen.

Tragically, only 34 of the 132 seamen survived the wreck that night making it one of the largest losses of life in the history of the United States Life-Saving Service.

Shortly after this incident, the Life-Saving Stations seasons were extended, and soon after, Keepers would man the stations year-round.

It is believed that had the Nags Head station been open, beach patrols would have spotted the stricken vessel and many more, if not all lives, could have been saved. Further tragedy happened the following day when the Superintendent of the Sixth District, Captain J.J. Guthrie, along with four other men, were drowned when their boat capsized in the rough waters as they were trying to come ashore after being lowered from the wrecking steamer, the B. & J. Baker. Captain Guthrie was trying to reach the survivors of the Huron to ensure they were getting all the care they needed.

As for Ensign Young and Seamen Williams, they were both recipients of a gold medal of the first class in recognition of their unwavering efforts that stormy night.