Island History: A spotlight on stories from the Outer Banks’ Life-Saving Service

The Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station (CLSS) is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year, as one of the seven original Life-Saving Stations to be built in North Carolina in 1874.

As such, the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station and Historic Site in Rodanthe will be sharing stories about the seven 1874 Outer Banks stations in the months ahead, leading up to the official October celebration of the United States Life-Saving Stations’ 150th anniversary in the state.

The following is the next of these Life-Saving Station feature articles to honor the #LegacyofLifeSaving, written by Jen Carlson for CLSS.

A Patient Soul – A Rescue by the Little Kinnakeet Life-Saving Station

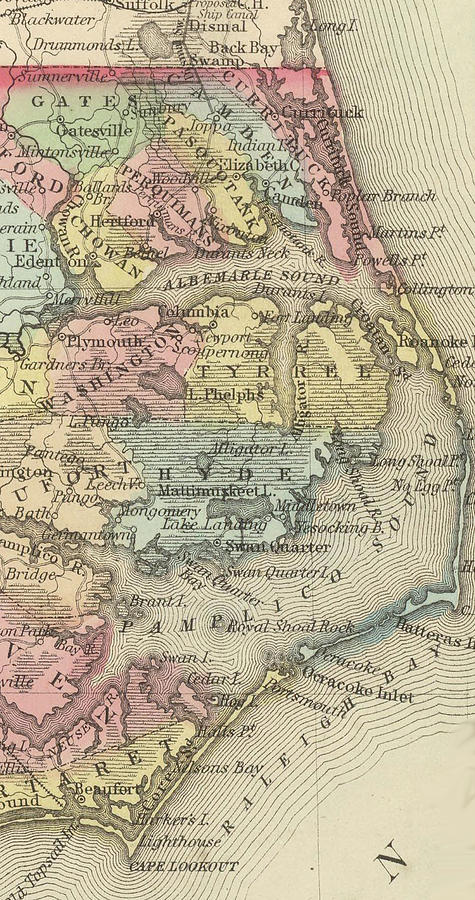

On October 5, 1881, the same storm that caused the Thomas J. Lancaster to wreck near the Chicamacomico station, forced a small schooner named the Charles to scud down the coastline.

When she neared the Little Kinnakeet station, she appeared to haul in towards land as if the captain of the vessel intended to purposefully beach her. The crew immediately started towards her with their apparatus. The Charles ended up getting stuck about a mile south of the station, and soon after, the Little Kinnakeet crew arrived on the scene.

The Charles had stranded herself so close to shore that one of the surfmen waded waist-deep out into the rough water with the whip-line in hand. He managed to climb aboard the vessel and tied off the tail-block to the foremast for the purpose of aiding the landing of the passenger and crew.

He found only three souls on board, two men and a boy. Amazingly, they refused to leave the vessel until all of their personal effects could be collected, and the captain even went so far as to lock himself into the cabin.

Unfortunately, while en route to the Charles, the experienced crew had seen another vessel off in the distance and knew there was the potential for another rescue to be needed due to the foul weather.

With no time to argue, the captain of the Charles was given an ultimatum that if he and the others wanted to be rescued, they would have to abandon ship now or the crew would leave, take care of the unknown vessel headed their way, and only then return to the Charles.

Wisely, the captain came to reason and quickly the crew of three were transferred to shore via the breeches buoy and were taken to the station.

The captain of the Charles later reported first encountering the gale the previous night and the vessel had some significant damage. By the time some repairs had been made, the storm had increased with such intensity that the captain felt he had to try to run ahead of the storm and ultimately decided beaching the vessel was the best chance of survival for him and his crew. After the storm passed, the vessel’s hull was undamaged, so the captain hired a company to haul her out of the water for repairs and then relaunch her into the Pamlico Sound. The three-man crew of the Charles remained at the station for the duration of the repairs.

As for the unknown vessel headed to shore, stay tuned next week to hear more about the havoc this tropical storm was causing for the brave surfmen serving along our coastline.

All in a Day’s Work at the Kitty Hawk Station

Sometimes it’s just being ready for trouble: On September 23, 1896, the Kitty Hawk station look-out reported seeing a steamer appearing to be floating without engines.

Experience dictated a rescue would be needed, so Keeper Samuel J. Payne summoned aid from adjacent stations and started up the coast with his own crew and beach apparatus towards the direction of the vessel.

The station crew reached the scene shortly after the steamer came ashore but between the combination of the wind, current, and only a light draft of four feet, the seventeen men from the Fred’k de Barry landed over the side of the vessel without accident and without assistance.

The men were taken to the station where they were provided with dry clothing. Throughout the day, surfmen landed personal belongings and all articles that could be saved from the vessel. The following day, all but three proceeded to Norfolk while the captain, mate, and chief engineer remained at the station for over a week while they waited for the steamer to be refloated so it could be towed to Norfolk.