Homecoming: Portsmouth Island descendants set to gather

From CoastalReview.org

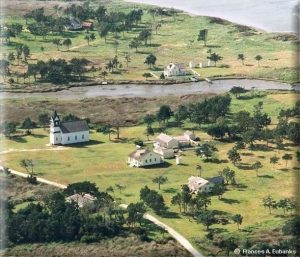

Now uninhabited and listed on the National Register of Historic Places and part of Cape Lookout National Seashore, the 250-acre Portsmouth Village established in 1753 was the largest settlement on the Outer Banks by 1770.

As the former port town’s bustling industry declined and the Civil War forced islanders to leave, the island’s population dwindled from 685 in 1860 to a mere 17 by 1956. After the death of Henry Pigott in 1971, Portsmouth’s last two residents, Marion Babb and Elma Dixon, moved inland.

Though the village just south of Ocracoke doesn’t see much foot traffic these days, hundreds will be showing up by boat – the only way to get there – Saturday, April 27, for the Portsmouth Homecoming. Coordinated by Friends of Portsmouth Island and Cape Lookout, the homecoming is held every two years.

Friends of Portsmouth Island Vice President Connie Mason said that this year’s homecoming will highlight the 130th anniversary of the U.S. Life-Saving Service Station, which was established here in 1894 and closed in 1937.

There will be an area for descendants to share family photos and scrapbooks, the post office will be open, as well as the schoolhouse, Annie and Theodore Salter House and Visitor Center, Methodist Church and the U.S. Life-Saving Station, which features exhibits of rescue methods.

“We have a hymn sing in the church about an hour before a program under the tent and then a covered dish lunch on the grounds after the program. Plates and utensils are provided by the Friends, so bring something yummy to share,” Mason said.

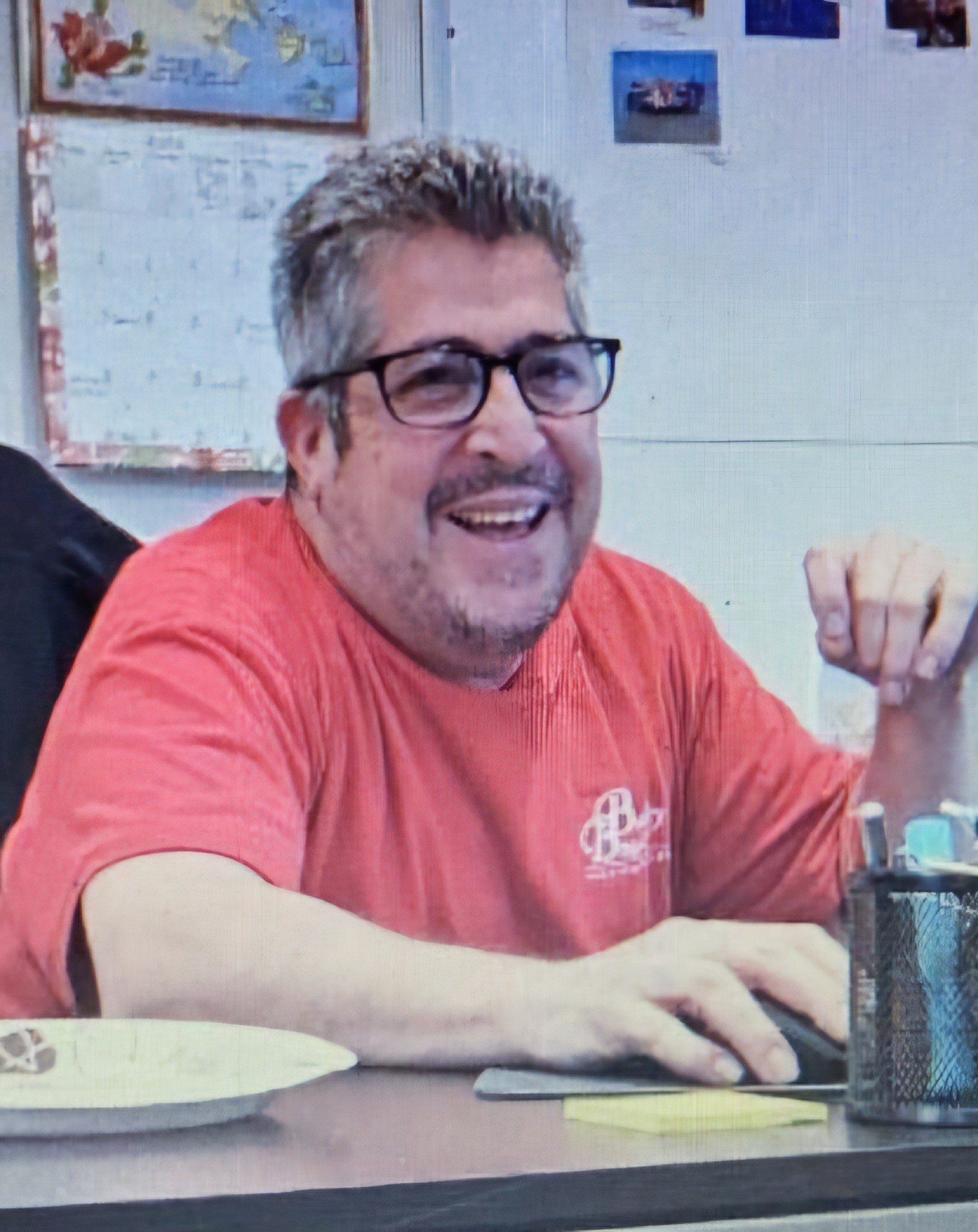

Friends member David Quinn is the grandson of the late Dot Salter Willis, one of the last people born on Portsmouth Island. He has been a history professor at Carteret Community College for the last 23 years and since 2022, has served as county commissioner representing the western part of Carteret.

His favorite part of the homecoming: “Getting to see friends and extended family members that I only get to see while they’re at the homecoming. Unfortunately, you just don’t get to see them except for that particular occasion. Getting reconnected with my family history and just being on Portsmouth Island itself is just an absolute joy.”

Quinn said he assumed the role of what he called “unofficial historian of homecoming” when his grandmother, who had recounted the history, died in September 2010.

Since 2012, Quinn has shared the history of the island from its earliest settlement during the Colonial period until it was taken over by the National Park Service in 1976.

Quinn said it seems like life was hard for the people of Portsmouth, but he doesn’t think they viewed their lives that way.

“In speaking with my grandmother, even having lived all the way until 2010 — she was born in 1922 — she yearned to return to Portsmouth,” Quinn said. He often includes her in his presentations on Portsmouth history, “and she would get very upset with anybody that referred to Portsmouth Village as a ghost town. She hated to hear people say that. She’d say, ‘No, no, Portsmouth is not a ghost town, it is still alive.”

This year, Quinn said his role is going to be slightly different.

Quinn was asked to fill the role of emcee upon the unexpected death of author and Portsmouth descendent Jim White.

He also has brought in his sons to help. He said his youngest, 16, led the Pledge of Allegiance at the 2022 program and is to deliver a portion of the history this year, and he thinks his older son will lead the Pledge of Allegiance.

About the homecoming, Friends of Portsmouth

Quinn told Coastal Review that he’s attended every homecoming since it was just a family gathering in the late 1970s, when he was very young, before it became an official event.

Mason explained that the Park Service held a homecoming in the early ’80s but the organizer was transferred to a different park, and no more where held.

“That was one impetus for the need for a Friends of Portsmouth Island group,” Mason said.

Mason said she served as oral historian for Cape Lookout National Seashore from 1980 to 1988.

“My area of collection was Portsmouth Village,” she said. “I could not have done a good job without the friendship and respect of the former residents who trusted me with the telling of their family histories and about their lifestyles on an isolated island.”

After leaving the park service to become curator of collections at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort, “I wanted to do more to help preserve Portsmouth” and began working with descendants, community leaders and others who love the village, Mason said.

The nonprofit Friends group formed in 1989 under the sponsorship of the Carteret County Historical Society and with the assistance and support from Jack Goodwin and Kay Hewitt, both now deceased, Feb. 23, 1990, became its “birthday.”

In 1991, the Friends began the campaign to reach more people and to build its membership by having booths at area festivals manned by devoted members. “Since those early days membership has grown,” Mason said.

Planning for the Homecoming

Quinn recommended that those who plan to stay in Ocracoke make overnight accommodations as soon as possible.

Visitors will also need to make ferry reservations starting in early April to travel from Ocracoke to the island with Rudy Austin at 252-928-4361. Cost is $25 per person, round trip.

Attendees can take the state ferry to Ocracoke from Cedar Island, or from Hatteras the morning of, and then catch the passenger ferry to Portsmouth from the same dock.

“The easiest way to come is to catch the earliest ferry from Cedar Island as a passenger only. No reservations required. Once at Ocracoke Rudy picks you up just as you get off state ferry, so there is no need to bring your car,” she said.

Mason added that there will be golf carts to tote coolers and those with difficulty walking.

Cape Lookout National Seashore Superintendent Jeff West encouraged dressing for the weather. “It can be hot or cold and wet in April. The wind may be blowing. It usually does,” West explained. “Insect repellent can be important if it is not cold or windy. It may be muddy. You will have to be able to endure a 20-minute boat ride, climb out of the boat, and walk down the dock.”

West reiterated that there will be walking, even with the transportation from the dock to the event. “Comfortable shoes are important.”

From the superintendent

West said preserving areas like Portsmouth is important, and the reasons vary.

Park service professionals will likely say they’re legally bound to preserve and protect cultural and historical artifacts, and “it is the very foundation of the National Park Service mission to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values” for the “enjoyment, education, and inspiration” for this and future generations.

“Most of us were attracted to the NPS in the first place by the mission, and most of us come to love and care personally about the areas we care for,” West said.

Historians will tell you that Portsmouth “was one of the most important ports of entry” in the state from about 1780 to 1860, and “maritime activities and development led in a major way to the success and importance of the state and in no small way to the emergence of the United States as a world power.”

Historians can point to the commerce generated to support this, from wood for shipbuilding, turpentine production, the trade in human beings, cotton, the list goes on and on. And, the fact that a marine hospital was built there, an early life saving station, a customs house was established, and so forth, West continued.

“They will also tell you it relates the story of a violent and harsh existence of people on a barrier island — the suffering and constant storms with little warning people endured, and they will tell you the history can teach us how to survive today,” West said. “They will tell you what came before us matters so that we do not repeat the mistakes of the past, and perhaps help us cope with our own struggles today — shared human experiences are a strong measure of humanity.”

From a descendant’s perspective, they will say Portsmouth is “about ‘place’ and capturing a piece of where they are from in their hearts and minds. Being able to walk the same paths, experiencing the same environment, seeing many of the same scenes provides that connection for many — a human connection that cannot be equaled by a passage in a book, or a video clip, or a family story handed down through time. We have the ability to go to Portsmouth and pretty much see it as it was … I think maybe that is why people appreciate it so much.”

West said the village is still recovering from Hurricane Dorian that hit the area in August 2019.

“Every structure in Portsmouth and four cemeteries were damaged by the storm, and several structures were destroyed,” he said. “It takes a great effort, many resources, and money to recover from a devastating storm like Dorian, especially in a remote place like Portsmouth.”

West explained that the national seashore has a dedicated historic preservation team “that has worked miracles to rehabilitate and harden the structures — hopefully making them more resilient for future storms.”

Hard decisions were made in the process, such as choosing what buildings could be saved with the limited resources at hand. They considered relative importance of the structures both historically and functionally, the condition and estimated costs of repair, the vulnerability of the buildings and what resiliency measures could be taken to help protect them from future storm impacts.

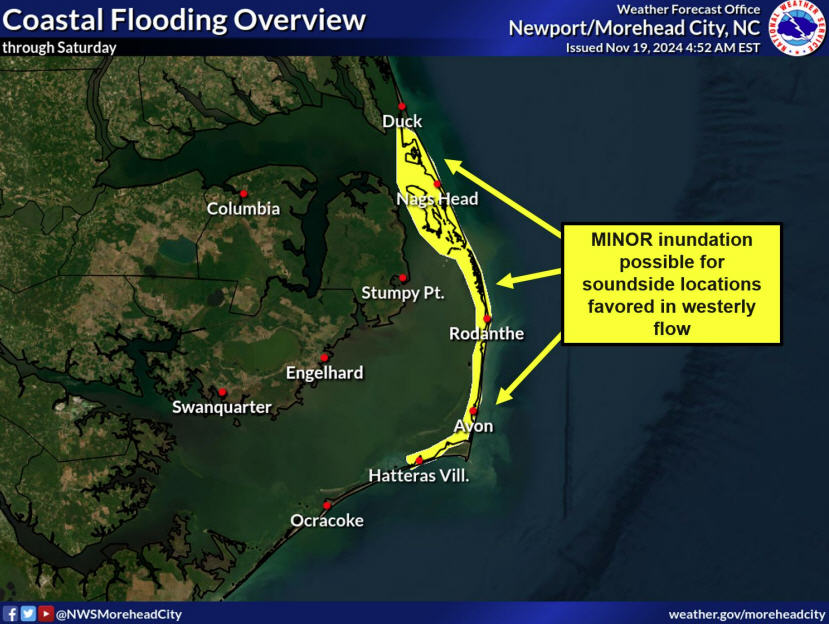

“And, then there is climate change,” West said. “Monthly flooding without storms continues to become more pronounced and frequent. All of these things figured in the equation.”

Only the Armtec House was completely destroyed by the storm, West said. The Frank Gaskill House will likely have to come down because it is too exposed and too badly damaged. The Mason-Dixon house, and the Wallace House are still awaiting repairs.

As a ranger, West said he looks forward to talking to and interacting with family and visitors. “Nothing like folks sharing personal stories and the meaning of the island — it adds the human connection.”