Island History: A spotlight on stories from the Outer Banks’ Life-Saving Service

The Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station (CLSS) is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year, as one of the seven original Life-Saving Stations to be built in North Carolina in 1874.

As such, the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station and Historic Site in Rodanthe will be sharing stories about the seven 1874 Outer Banks stations in the months ahead, leading up to the official October celebration of the United States Life-Saving Stations’ 150th anniversary in the state.

The following is the next of these Life-Saving Station feature articles to honor the #LegacyofLifeSaving, written by Jen Carlson for CLSS.

Whatever Means Necessary – A historic rescue by the Little Kinnakeet Life-Saving Station

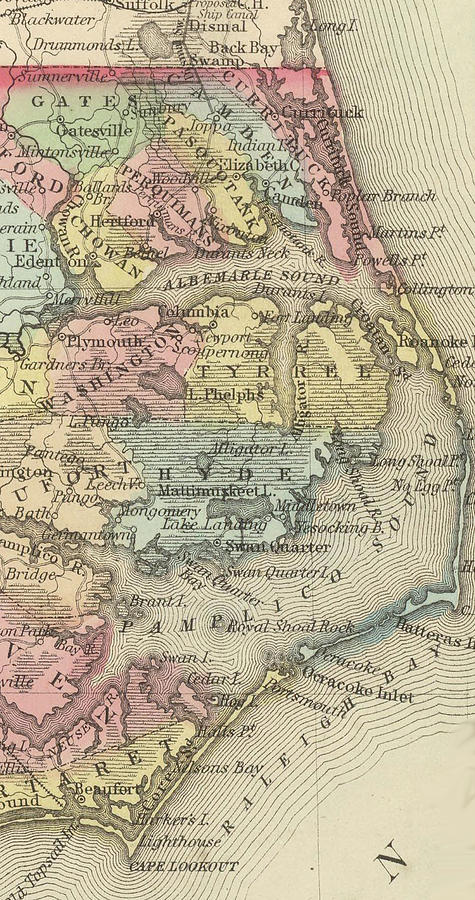

Just after midnight on February 20, 1893, the north patrolman from the Little Kinnakeet Life-Saving Station discovered a large schooner about 2.5 miles north of the station.

While not a stormy night, the darkness made it hard to see, and the Nathan Esterbrook, Jr.’s master had miscalculated, causing the vessel to run aground about 400 yards from shore.

The patrolman hurried back towards the station to sound the alarm. Keeper Edward O. Hooker called both the Gull Shoal and Big Kinnakeet stations for an assist before climbing to the lookout tower to burn a flare alerting the shipwrecked sailors that help was on the way.

The crew started hauling the beach cart while Keeper Hooker drove a horse cart loaded with supplies. He encountered the Gull Shoal crew en route and recruited a few of the surfmen along with a horse to help his crew pull the cart.

About two hours after notification, the crews arrived on the scene and rapidly set up the Lyle Gun using the lights from the schooner as a guiding point. The first shot was fired into the darkness, and after a short period of time with no movement indicating the line was being hauled aboard, Keeper Hooker prepared for a second shot. It was later learned the first shot reached the vessel but ended up rebounding off the forestay.

The second shot was a miss but the third landed across the foregaff and the sailors promptly began hauling the whip. Again, the lifesavers were relying on the vessel’s lantern lights and signals from the shipwrecked crew to guide their actions in the dark of the night.

An unexpected wind change pushed the hawser across the headstay, but the signal to haul away was given by those on board. When the first sailor was brought to shore, he was unconscious, and the fear was he had drowned due to being underwater for most of the journey. Efforts were successful in reviving him and he was loaded into one of the carts and was immediately taken to the station.

In the meantime, the gear had become fouled, so Keeper Hooker made the call to launch the surf boat to retrieve the remaining sailors. Unfortunately, the wind had progressively gotten worse and a strong current had developed that kept pushing the surf boat away from the stricken vessel. Eventually, the crew had to abandon the effort and return to the beach.

Daylight had now broken, and Keeper Hooker signaled the sailors to move the hawser and whipline to the lee bow. A team of surfmen set about to untangle the lines that had become fouled earlier in the rescue and a second team was sent back to the station to retrieve the LifeCar. Once they returned, the car was hung on the hawser in place of the breeches buoy and four successful trips were made to retrieve the remaining eight sailors from the Esterbrook. Through all this, the vessel held together which infinitely helped make the rescue a success after the challenges that had to be overcome.

Sadly, the second mate who had been revived onshore passed away from his injuries later in the day. From his own testimony, as well as testimony from his shipmates, he had been previously injured before leaving the schooner, and the collision with the headstay as the wind picked up attributed to his internal injuries. He was prepared for burial using clothing provided to the stations by the Women’s National Relief Association and interred with the lifesaving crews and his shipmates in attendance. The survivors remained at the station overnight before leaving on a wrecking steamer headed to Norfolk.

Captain Kelsey left a statement on behalf of the Esterbrook crew with Keeper Hooker expressing his thanks for how his crew was treated and indicating he found no fault in the lifesaving crews for the second mate’s death as they did everything possible to save his life.

While the events that led to the rescue were not extraordinary, the challenges that the crews had to overcome proved why the daily training each station did proved to be so important. From reviving the apparent drowned man, to setting up the breeches buoy apparatus and even launching the surfboat, these crews practiced these skills weekly which kept them ready for the moments they were necessary.

All in a Day’s Work at the Whales Head Life-Saving Station

Sometimes it’s about redirecting: The tug, Hercules, was unable to locate the dismasted schooner for which she was looking. The Whales Head Life-Saving Station crew (formerly known as Jones Hill) launched their surf boat to intercept the tugboat as it was standing back up the coast after giving up the search. They redirected the Hercules crew to Kitty Hawk where they located the schooner in order to tow her back to Norfolk.

For more stories like these, visit the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station where history is alive.