Keepers of Light Amphitheater dedicated in Buxton

It would be hard to imagine a more fitting outcome to the saga of the storm-tossed Cape Hatteras Lighthouse stones.

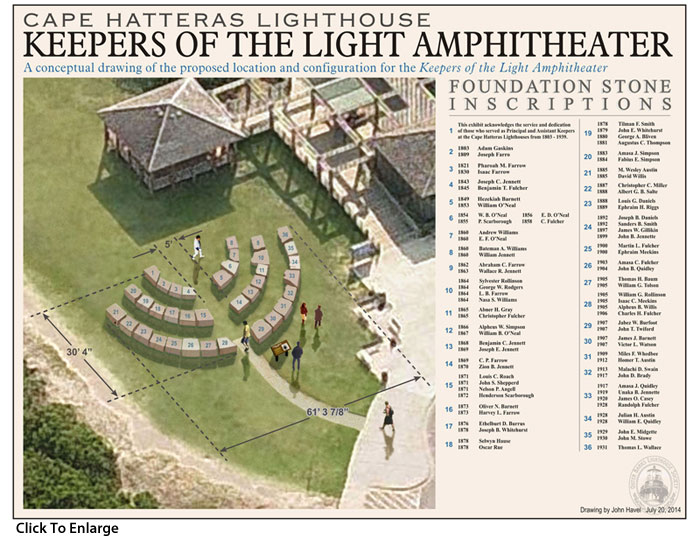

Remnants of the foundation at the original location on the beach of the 1870 lighthouse, 36 huge blocks of granite engraved with the names of the lighthouse keepers, now serve as natural outdoor seating in front of the relocated tower.

On an unseasonably warm and sunny morning, about 100 folks, many of them descendants of the keepers, attended a brief ceremony on Saturday, Nov. 7, formally dedicating the Keepers of the Light Amphitheater on the grounds of the Cape Hatteras Light Station in Buxton.

“This tower does not see,” said Dave Hallac, Superintendent of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, with the licorice-striped beacon towering directly behind him. “The lighthouse does not have a heart. It is the keepers . . . that are the heart of the lighthouse.”

The audience sat two or three together on each of the irregularly shaped blocks, arranged in a split semi-circle in three rows facing the lighthouse, listening to Hallac and representatives of the Outer Banks Lighthouse Society and Hatteras Island Genealogical and Preservation Society. All three had focused on finding a meaningful way to exhibit the stones that had barely escaped demise on the beach.

Originally marking the place the lighthouse had stood before it was moved in 1999, the so-called “Circle of Stones” had been covered by sand over the years and even shoved around during several storms. The Lighthouse Society had earlier paid about $12,000 to have all the names of the keepers engraved on the side of each stone.

After much discussion with the Park Service, the cleaned and polished granite blocks, once part of the layers of granite supporting the lighthouse, were moved to their new home on the edge of the lighthouse grounds in February.

The stones, weighing between 2,300 pounds to 5,700 pounds, sit on compacted sand and clay covered with white crushed shells and stone. Each block is unique — some have large dents, others are streaked with blue and red, and some even have pieces of lighthouse brick embedded in them.

“The stones began their lives in New England,” Richard Meissner, the Lighthouse Society’s vice-president,” said in his remarks. “They, like many of you, are misplaced Yankees. I guess they’re Southerners now.”

Meissner said the Society was determined to not leave the stones buried at the revered area where the lighthouse once stood.

“So this is another sacred place,” he said, asking the audience to join him in a silent prayer to dedicate the repurposed stones at the new location. “But, symbolically, may the circle be unbroken.”

Jennifer Creech, president of the Genealogical Society, and Diana Chappell, president of the Lighthouse Society, took turns reading the names of the 83 principal and assistant keepers of the 1803 and 1870 Cape Hatteras lighthouses, while Dixie Burrus Browning, a Frisco author and a keepers’ descendant, rang a bell after each name.

Bett Padgett, the former Lighthouse Society president, followed by performing her song, “ Always in Our Heart,” which she had written in March 2014 about the stones.

“Who really knows the way to the sea? Our shoreline is ragged and worn,” she sang, while strumming her guitar. “Who are the men whose names we see here? Why is the bond so strong? This foundation of men, like this foundation of stones, will never be broken apart.”

The ceremony was a closure of sorts for those involved for years in preservation of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

Ellis Cowling, a distinguished professor at-large emeritus at N.C. State University, shared a stone during the presentation with his wife Bettsy.

Cowling, a member of the National Academy of Sciences, said he was one of the people who helped select International Chimney as the mover of the lighthouse. He had also been the scientist who had studied the biochemistry of the supportive timbers under the lighthouse before it was relocated to its current location one-half mile inland.

“Those timbers were still in excellent condition,” he recalled after the ceremony.

Cowling, who will be 83 in December, joked that his wife finds his lighthouse work more interesting than nearly anything he has done. But by his smile, it appeared that he shared her appreciation.

Keepers of Light Amphitheater dedicated in BuxTon….WITH SLIDE SHOW

“This was one of the real adventures in my career,” he said.

Another enthusiastic Cape Hatteras Lighthouse lover is John Havel, whom some credit as the designer of the amphitheater.

Havel, a graphic designer and researcher from Raleigh, said that the real story is that Padgett had passed on to him a blotchy diagram of the amphitheater concept scribbled years ago by a Park Service engineer.

After it became obvious that the Circle of Stones was not going to be able to stay, Havel said, the Park Service did not want to re-do the circle in a new area, since it could be mistaken for the original lighthouse location. So when the early amphitheater sketch reemerged from the records, Havel, who works as graphic designer for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in Durham, volunteered to create a “nice drawing” of the concept.

“I said, ‘Bett – take this to your meetings. This is what it would look like,’” Havel recalled.

Although the Park Service worked off of his fancy three-dimensional drawing, he emphasized, the credit for the original design lies with the Park Service.

Hallac, the park superintendent, said that since most the work for the project was done in-house, it is difficult to determine what it cost to move and rearrange the stones.

Eventually, he said, the park would like to develop an interpretive program about the stones.

Meanwhile, any of the 400,000 annual visitors to the Light Station will be able to rest a spell on pieces of the former granite foundation while contemplating the majesty of the lighthouse the stones once supported just yards away.

Padgett said that she credits U.S. Rep. Walter Jones, R-NC, with helping the two preservation groups to work with the Park Service in conservation of the stones and their story.

“I thought it was wonderful that the stones are safe,” she said.

Padgett did not see the rescued stones in their new amphitheater configuration until the night before the dedication.

“There was no moon – only stars,” she said. “I cried. It was haunting without the moon. We could see the stripes in the lighthouse.”