“What a story, if only the live oaks could talk.”

That is the caption Ocracoker Earl O’Neal wrote to go with a photograph of the Outer Banks, as portrayed in his latest, almost completed book, “A Historical Almanac of the Outer Banks; A Long Voyage Over the Last 488 Years.”

The book, co-written with Hatteras Islander Mel Covey, is a pictorial history of the Outer Banks, and includes Portsmouth, Beacon, and Shell Castle islands.

The same statement could be applied to Earl O’Neal himself — what a story!

In Earl’s yard on Back Road is a special live oak, named the Buttonhole Tree by his deceased wife, Dee. It could probably tell some great tales about Earl and all his undertakings throughout his life, if it could only talk!

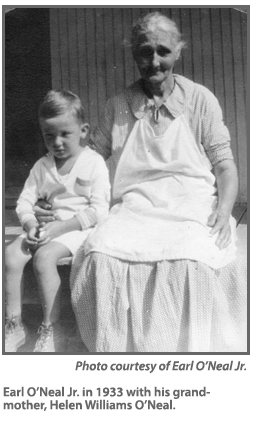

Earl O’Neal Jr., 85 years old, has island roots on his father’s side that go back to the early 1700s, and include many of the original Ocracoke families. The son of Earl Williams O’Neal and Luisa Gutt, an immigrant from Prussia, he grew up in Philadelphia. He spent his summers at his father’s home island and was christened at the house of his grandfather, “Pop-Pop Ike” (Isaac Willis O’Neal) in Ocracoke at the age of 5 weeks.

Earl’s memories of those summers include sitting on the porch with his grandfather, who told him stories of the sea and taught him to tie knots, going out to the duck blinds to hunt ducks and geese with his Uncle Rashe and his father, and fishing for bluefish and trout off the side of the mailboat, the Ocracoke. He recalls with delight the still warm, light rolls with butter his Grandmother Helen made, and eating 18 of them before dinner one day. Movies at the Wahab Village Motel, dances at the Spanish Casino, and sailing in his Uncle Wahab’s sailboat are some of his other treasured memories.

Also etched into Earl’s memory is his Pop-Pop’s Model T (or A) car, which he says his grandfather had driven through the side of Old Bob’s stable on the day he got it. Later, when Earl, age 3, was at the morning service of the Northern Methodist Church next to his grandparent’s home, he saw the car go by and yelled out, loud enough for all to hear, “There goes Pop-Pop’s car!”

Earl laughs as he tells this story: One dark, moonless night, when he was about 6 years old, he went flounder gigging with his dad, Oscar Jackson, and Sam Keech in a sailboat. They sailed out the Creek, headed Up Trent, and anchored in shallow water. Then they took their kerosene lanterns and flounder gigs and proceeded to gig about 40 fish, which they strung on a big line, carried between two of the men. At that point, they realized that they had forgotten to leave a lantern on in the boat. They were unable to find it in the pitch dark, and finally had to wade to the shoreline and find their way through the trees and underbrush to walk home. Someone went back for the boat the next day.

Earl’s father went north to find work, as did many of the island men in the early 20th century. He had a job as a rigger’s helper at the Cramp Ship and Philadelphia Navy Yards, and according to Earl, he op ened his home to friends and relatives from Ocracoke who came looking for work in the Great Depression. Earl Jr. grew up in a row house that was only 12 feet wide. He got a job at the age of 8 running errands for a candy store, and by 12, he was unloading lumber trucks for a company called Arctic Refrigeration.

In 1948, he joined the U.S. Navy Reserve and during the Korean War enlisted in the Army Security Agency Army Signal Corps. He was selected as one of the first eight people to become part of the U.S. Army Cadre for the SL-1 Nuclear Power Plant. He went on to earn a diploma in Nuclear Engineering from the University of Virginia, and worked on ways to use nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, such as the generation of electricity.

After leaving the Army, Earl stayed in Idaho, where he was last stationed, and continued to work with nuclear power. He was employed by various companies throughout the country. He eventually became the assistant division head in charge of engineering personnel for all control systems at 15 nuclear and 34 fossil fuel power plants, under his design, and was chairman of one of the first Instrument Nuclear Standards to be used in the U.S.

In 1965, he changed careers and became a sales engineer and later an instrument and controls system engineer, living in Illinois, and working for a number of companies in several states. In 1988, he joined Nuclear Energy Consultants, setting up an engineering office to support the nuclear industry in the Midwest.

Early on, Earl had met a young woman, Delores Grace Collins, at a Philadelphia trolley stop and had fallen in love. While it did not work out at the time, when he returned from military service in 1955, they reconnected and were married. Earl and Lori, as he fondly called her, spent their two-week honeymoon at Ocracoke, where “Lori, Uncle Rashe, and I had a great time, and spent a lot of time at the beach.” Earl adopted Lori’s daughter, Sharen, and they later had a son, Mark.

Earl and his wife, who came to be known as Dee to most islanders, moved to Ocracoke in 1990, building a home where his grandparents’ house had stood. He has since devoted himself to learning and writing about all aspects of Ocracoke history.

He is the author of a number of books, covering such topics as the U.S Coast Guard and Navy Base during World War II, the history of island families such as the O’Neals, Howards, and Williams, and an autobiography titled “One Boy’s Life.” He has served as chairman of various Ocracoke boards and committees, a director of the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras, and the Outer Banks History Center Associates in Manteo, and designed Ocracoke’s Civil War marker as part of the Dare County Civil War Trail.

On Dec.15, 2009, Earl O’Neal Jr. was awarded North Carolina’s highest civilian honor, the Order of the Long Leaf Pine, for service to his community.

He has, in the intervening years, continued his work on Ocracoke history and was instrumental in having two World War II markers put in place on the island to commemorate the U.S. Navy Loop Shack Hill and the U.S. Navy Beach Jumper. He gave lectures in the Ocracoke Preservation Society’s Porch Talk series and at the North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teachers facility, located in the old Coast Guard Station.

While Earl has suffered some health setbacks recently, he has hopes of finishing his last book and continuing to explore and write about Ocracoke history.