A wreck of little auks

The cold open waters off Newfoundland may not seem like an ideal location to spend the winter. But it is for some, especially the Dovekie (Alle alle), a small seabird known as the Little Auk in Europe.

Despite their diminutive size, weighing only seven ounces and with a wingspan of 15 inches, these black-and-white birds in the alcid family are adept at handling the frigid temperatures, rolling waves and high winds of its wintering habitat.

But sometimes a powerful storm system can be too much even for them.

One such storm occurred around Dec.18, 2023. With near-hurricane winds and heavy rainfall, it caused coastal flooding and multiple power outages all along the East Coast down to Florida. This storm also struck the Canadian Maritime provinces and uprooted thousands of floating Dovekies, literally blowing them into Maine, here on the Outer Banks and all the way to South Carolina. One was even seen as far inland as Burlington, Vermont.

Irruptions, flights and wrecks

To understand the significance of what happened to the Dovekies, let’s start with how birds react to shifting environmental conditions.

When large numbers of a bird species stray into territories outside of their normal distribution range, especially for northern birds wintering farther south, the phenomenon is colloquially described as an invasion, irruption or a flight. A principal cause for these incursions is a scarcity of food in their normal range.

Red-breasted Nuthatches and Pine Siskins are two seed-eating species that breed in Canada and the northern United States. Some years they appear in fall and winter in large numbers in North Carolina, farther south than usual.

Red-breasted Nuthatches feed in winter primarily on the seeds of conifers. As their name implies, Pine Siskins forage on seeds of pines and many other trees such as alder, birch, sweetgum, and maples.

Whether there will be an irruption year can be determined by the food crop in their wintering range, which varies from year to year. To produce a healthy crop, trees need the right combination of temperature and rainfall. especially in the spring.

Each fall, the Finch Research Network (FiRN) issues a Winter Finch Forecast to project movements of finches and other berry- and seed-eating bird species by analyzing mast crops (the fruit of forest trees and shrubs, such as seeds, acorns, other nuts and berries). This release is closely watched by those in the bird feeder industry.

Here is their forecast for Red-breasted Nuthatches for this fall/winter:

Populations in the boreal forest should have small flights this year. Balsam Fir in the boreal forest, which is not infested with Spruce Budworms, has a good cone crop. This crop should hold many nuthatches closer to home this winter.

Anecdotally, that seems correct. The Hammock Hills area on Ocracoke Island has lots of longleaf pine trees and is described by John O. Fussell III in his 540-page “Birder’s Guide to Coastal North Carolina” (1994-UNC Press) as one of the best locations in coastal North Carolina to see (and hear) Red-breasted Nuthatches even when they are scarce elsewhere in fall and winter. Although much of its nature trail has been inaccessible due to floods and trail damage, these nuthatches were not seen or heard during the island’s Christmas Bird Count on Dec. 30 in the open areas, nor on several forays there.

However, the FiRN predicted an irruption year for Pine Siskins, which rely on different food items than Red-breasted Nuthatches:

With the poor White Spruce crop in much of the boreal forest, there should be a moderate to possibly strong flight of siskins southward this fall.

Overpopulation can be another reason for an irruption.

During the 2013-2014 winter many Snowy Owls showed up in North Carolina and in other states. One explanation is that their nesting season in the tundra was overly successful due to an abundance of lemmings, their preferred food source. These conditions permitted more hatchlings to fledge. For Snowy Owls to survive an arctic winter, they need a huge territory to forage. So, adults will drive out other owls including their own offspring, forcing the young birds to fly south. Most of the many Snowy Owls showing up in the United States that period were young birds.

Extreme cold temperatures and heavy snowfall can impact the ability to forage prompting birds to move to areas with better feeding opportunities. Environmental changes in large areas due to forest fires or deforestation can also trigger an irruption.

A look at a wreck

Setting aside natural mortalities, most birds that come farther south in an irruption year are expected to survive and return in the spring to their nesting grounds.

Unlike irruptions, which occur irregularly but predictably due to the availability of food or other environmental factors, there are instances when many birds appear because of extreme weather and in these cases, there is a more colorful but more ominous descriptive term — a wreck. Like a shipwreck.

This is when seabirds in large numbers show up that are exhausted, disoriented and end up getting stranded on land. Facing starvation and trauma, many do not survive. A wreck is what happened to Dovekies this past December and caused so many to be found in eastern North Carolina, including unusual locations.

A wreck is of great interest to researchers as it can provide an insight into avian species and the environment. Ian J. Stenhouse and William A. Montevecchi, co-authors of the Dovekie species profile in “Birds of the World,” the extensive online publication by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, have documented the history of Dovekie wrecks.

“Dovekie wrecks occur periodically and are often extensive and are likely storm-driven to a large extent,” said Montevecchi, a university research professor of psychology, biology and ocean sciences at Memorial University of Newfoundland. “The North Carolina wreck is unusual indeed though not historically unprecedented. During storm conditions that are extensive in space and time, physical stress increases the need for energy intake while sea state and turbulence can deter efficient feeding — hence hypothermia and starvation will follow in a few days.”

“Wrecks like this are something of a regular occurrence for seabirds but seem to have been increasing lately with climate change producing stronger and more frequent storms,” said Stenhouse, who is now director of the Marine Bird Program at the Biodiversity Research Institute in Portland, Maine.

Whether to describe a massive incursion as a Dovekie flight or a wreck can be tricky.

“I’m not sure if there are technical definitions for these terms… they may be used by some interchangeably,” Stenhouse said. “But in flights, large numbers of birds are pushed into coastal areas by strong onshore winds, but not necessarily blown onshore. Once the winds abate, they may be able to relocate back out to sea.

“On the other hand, wrecks I think of more as mass mortality events where extended periods of harsh weather weaken birds that are then driven fully ashore by a major storm, resulting in an observable die-off.”

North Carolina has indeed had Dovekie wrecks reported over the last century, some featured in local newspapers and often coinciding with those of other states, but 2023’s may be one of the largest and many took notice.

“Certainly, this one was not unique, but probably unprecedented for huge numbers far south of Cape Hatteras, i.e., Wrightsville Beach into South Carolina waters,” said Harry LeGrand, a zoologist, retired from the NC Natural Heritage Program and considered the foremost authority on the birds of North Carolina. “I cannot fathom a count of over 1000 from Johnnie Mercer’s pier, like Jamie Adams had a few weeks ago.”

LeGrand is referring to a report by Jamie Adams on eBird, Cornell’s massive bird sighting database, of 1,079 Dovekies at Johnnie Mercer’s Pier in Wrightsville Beach on Jan. 6. Interestingly, one observer reported seeing just one individual there the following day.

There were lots of other reports and many photos of them posted on social media asking, “What is this strange-looking bird?”

“I was impressed with how many I saw flying by Shell Point on Harker’s Island during the storm the other week this month,” said Jon Altman, supervisory biologist at Cape Lookout National Seashore.

The Outer Banks Wildlife Shelter Inc. in Carteret County received lots of calls about stranded Dovekies being found on land and they took in about 30 individuals. “Those that were brought to us were severely emaciated and in weakened condition, said Kelsey Gaylor, a wildlife rehabilitator. “So, despite our best attempts, none of them survived.”

Lou Browning, executive director of Hatteras Island Wildlife Rehabilitation in Frisco, said his center is not equipped to handle Dovekies. It focuses primarily on birds of prey, but they did receive lots of calls from people seeing them, he said.

On Ocracoke Island on Jan. 4, eight individuals were seen in Ocracoke’s Silver Lake harbor. There were reports elsewhere on the island including Springer’s Point (Ocracoke Inlet), in the ocean just off the 15-mile beach, on the sound side of the island, in Oyster Creek and several were seen stranded in the dunes, just off the beach.

After the initial excitement of seeing so many Dovekies over a period of two weeks or so, the numbers of live birds quickly diminished.

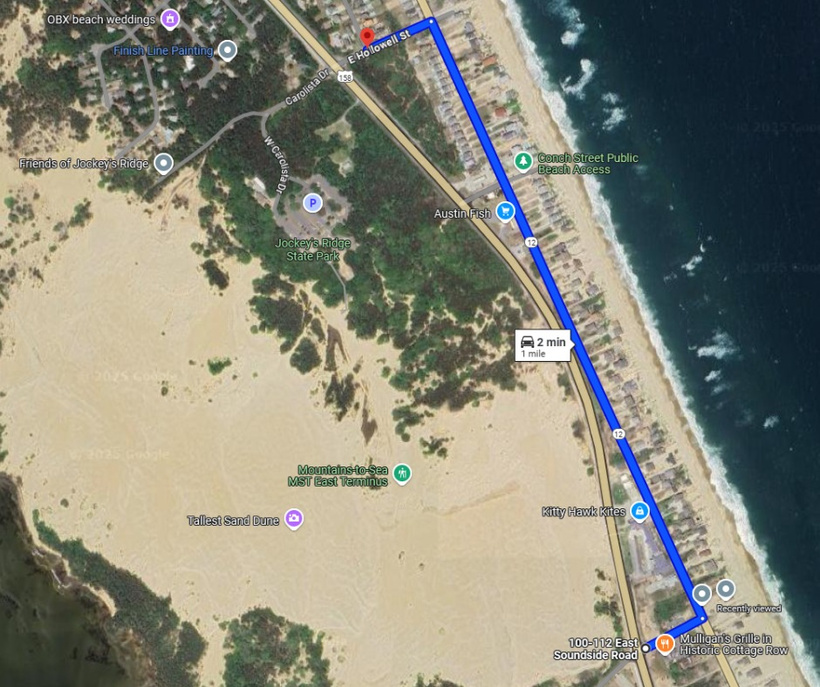

The Carolina Bird Club held their winter meeting in Nags Head Jan. 19 to 21 that included 40 regional fieldtrips. This popular event attracts many of the top birders in North Carolina. So, it wasn’t a surprise that an impressive number of species — 169 — was tallied from these field trips at the club’s evening banquet. Only one Dovekie was reported.

Although the National Park Service’s Cape Hatteras National and Cape Lookout National Seashores, which covers about 146 combined seashore miles, and the NC Wildlife Resources Commission (NC WRC) did not keep a tally of dead Dovekies, there were many.

One islander counted 20 carcasses on a two-mile walk on Ocracoke Beach in mid-January. On Hatteras Island, there were many reports of dead Dovekies on both the ocean and sound side and alongside NC Highway 12.

“We are not counting the dead Dovekies,” said Altman about Cape Lookout. “They are probably similar [in number] to what you are seeing up on Ocracoke.”

Carmen Johnson, a NC WRC wildlife diversity biologist whose focus is waterbirds, heard from different volunteers, partners and wildlife rehabilitators up and down the coast who were finding or receiving dead or stranded Dovekies. “I got reports of 10 here, and four there on different days but we did not have a count of them this year,” she said.

A week after observing the eight active feeding Dovekies in Silver Lake Harbor, only one was still present. During that time, one was seen being eaten by a Great Black-backed Gull on a dock. Predation may have accounted for some of the others’ disappearance.

The Plight of a bad flight of these little auks

Dovekies forage mostly on planktonic crustaceans by diving as deep as 100 feet, using their wings for propulsion and feet for steering. They are also strong flyers.

Unfortunately, they are not triathletes. Like loons and many other seabirds, they are unable to take off from flat ground. To fly, they need to take off from water or launch themselves into the air off rocks and cliffs. So, if one is blown onto land, unless it gets extraordinary assistance, it will perish. This is why so many dead birds were found on land.

Yearly, Dovekies do show up in small numbers on the Outer Banks in fall and winter. Jennette’s Pier in Nags Head at times can be a good spot for finding them and other unusual seabirds such as Parasitic Jaegers and Razorbills, another auk. Pelagic sea birding trips run by Brian Patteson are an opportunity to see many more Dovekies offshore.

Single-egg nesters, Dovekie are highly social and have huge breeding colonies in the upper North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. The largest colonies are on Baffin Island, Greenland, Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, Iceland and Novaya Zemlya, an archipelago in northern Russia notoriously known as a nuclear bomb test site by the former Soviet Union. None of these locations is easy to visit.

While disheartening to observe, one can be reassured that a Dovekie wreck with high numbers of casualties will not threaten their population.

Estimates of the world-wide Dovekie population are just that and numbers vary widely.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red list estimates the numbers between 16 and 36 million individuals. Other estimates are even larger. These numbers give the Dovekie the distinction as one of the most populous seabirds in the world.

Although the high population numbers are impressive, one must be cognizant that the Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) with its many variants is lurking. This bird flu has been devastating to nesting seabird colonies in northern Scotland, especially Great Skuas, and throughout much of the world.

Up to now, there has not been any indication of HPAI in the Dovekie nesting colonies of the Arctic Seas, according to Montevecchi.

The carcasses of four dovekies on Jan. 10 were sent to the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study (SCWDS) for diagnosis by NC WRC, according to Sara Schweitzer, assistant chief of NC WRC’s Wildlife Management Division. The report returned, Feb. 7, attributed the cause of death to emaciation (starvation). Avian influenza viruses were not detected.

So, how many Dovekies in this latest wreck survived? The number of carcasses though significant, were not even close to the number of observed live birds. Did the thousand-plus Dovekies that showed up for a day at Wrightsville Beach head back to sea with the eventual return north?

Two experts offer a glimmer of hope for these little auks. “These birds are resilient and there are likely many survivors. As for mortality estimates, we can only scale up from body counts,” said Montevecchi.

“Some starved, some were predated, and probably most headed back farther offshore with west winds (speculation on that), and headed back north offshore (also speculation),” said LeGrand. “We will be interested in what Brian [Patteson] turns up on February pelagic trips, plus what folks from shore see in that month.”

Peter Vankevich is co-publisher of the Ocracoke Observer and host of “What’s Happening on Ocracoke” on WOVV, Ocracoke’s community radio station.”