Better Beach Data Goal of DUNEX Project

It should be no surprise to science lovers on the Outer Banks that an ambitious and potentially breakthrough coastal project that kicked off this month is centered here at the Army Corps of Engineers’ Field Research Facility, long a hive of scientific innovation and invention.

The site, informally known as Duck Pier and officially as the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center’s Coastal and Hydraulics Laboratory’s Field Research Facility, is facilitating a new pilot study staged on the Outer Banks from the Virginia border to Cape Hatteras.

Called DUNEX, for During Nearshore Event Experiment, the study’s mission is to improve the ability to collect beach data during storms. If what’s past is prologue, the Outer Banks will provide a rich supply of storms to research. Produced by a collaborative of scientists, the study is planned as a precursor to next year’s full experiment, furthering research to deepen understanding of how the coast responds to the effects of climate change.

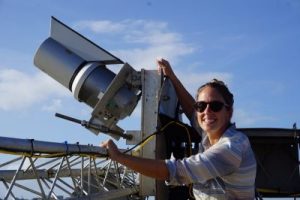

“We’re trying to align the experiment with the start of the hurricane season, into the fall nor’easter season,” Katherine Brodie, a research oceanographer stationed at the Duck Pier, said in a recent interview. “The pilot study is really an opportunity for the research teams to come together.”

Scientists at the Corps’ pier will be working with numerous researchers from public agencies, academic institutions and nonprofit or industry entities, including the National Park Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; the U.S. Geological Survey; the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory; the North Carolina Department of Transportation; East Carolina University, North Carolina State University, University of North Carolina and numerous other universities; the Woods Hole Oceanic Institution; and Dewberry and the North Carolina Coastal Federation.

Brodie said stakeholders will bring their area of expertise to the collaborative, working individually or in teams. For example, she said, Virginia Tech will work with a researcher and three or four graduate students. That team will be studying geo-technical properties of sediment, such as how well sand holds moisture and how easily it erodes, measuring with instruments deployed in the surf zone or on amphibious vehicles.

A critical goal of DUNEX researchers, Brodie explained, is to find a better way to collect data when waves and currents are most active, long a difficult challenge with sensitive instruments and dangerous conditions. But better data will translate to better predictions.

“We want to make those measurements during storm events,” Brodie explained. “The idea is we set (instruments) up before a storm, and we collect good data during the storm.”

Current meters, wave height sensors, video cameras and drones will be just some of the technical wizardry in the scientists’ toolboxes. Some of the most advanced instruments are located at the Duck facility. For example, two video cameras, one mounted on the pier and the other on a 25-foot metal pole sunk into a dune on the north end of the property, provide high resolution maps of the beach “every hour of every day,” Brodie said.

There’s only one other place in the world with such equipment, she added.

Preparations for #HurricaneDorian included maintenance of instruments deployed by coastal scientists to investigate overwash processes as part of a collaborative research effort. #DUNEX #OBX pic.twitter.com/9ixSyTWrEX

— Michael Flynn (@RippleEnviro) September 3, 2019

“So we can now see how the beach changes in response to the changing waves and tides,” she said. “We used to go out once a month and take measurements,” which had involved walking around the property with a GPS instrument.

When the 1,840-foot concrete pier was built in 1977 as part of the Corps’ Coastal and Hydraulics Laboratory, there was little known about coastal processes. But with the slew of instruments at the pier, as well as specialized nearshore vehicles invented at the pier, the pier has gained recognition worldwide for its cutting edge coastal science and massive collection of long-term coastal data.

Cameras that take 3D images of waves breaking on the shoreline are more recent example of gee-whiz technology at the research pier. Before, Brodie said, a sensor would measure the wave as it broke at one location. Now the image can be made as the wave is breaking.

“Understanding the shape of the wave as it breaks helps us understand which direction it will move sand on or off the beach,” she said.

Measurements will also continue to be taken with the reliable instruments that have provided good data for 30 years, Brodie added, including the 8-meter wave array, a series of instruments installed on the seafloor at the pier, and offshore wave rider buoys, one in 50 feet of water and another in 70 feet of water.

All the new data that DUNEX researchers collect will be compared with historic data.

“That gives great context to these new measurements that we make,” Brodie said.

The project is part of the ongoing efforts of the U.S. Coastal Research Program, a national scientific research program that coordinates collaboration of scientists in the public and private sectors and fosters community partnerships. Established in 2014 to answer the need, both societal and scientific, for a sustained approach to address coastal challenges, the program provides workshops for the public and grant funds for research and academic programs.

But the DUNEX launch is an example of the heavy lift involved in pulling together multiple stakeholders and pots of money.

In a press release announcing the project, Brodie described the “interesting challenge” involved in something akin to herding cats.

“There hasn’t been one funding source, so there are no real requirements for participation, and no one person in charge,” she said in the statement. “We’re dealing with multiple government agencies, multiple academic institutions, all while trying to engage our local communities – there have definitely been some bumps in the road.”

At the same time, she lauded the digital era of accessible and collaborative science, and the ability to bring communities together. “Some things have worked better than others,” she said, “but communication has been key.”

The full experiment is expected to start in fall 2020 and continue into winter 2021.

Brodie said that the project will include opportunities for the public to engage with researchers.